When the remote threat of Ebola spreading in the United States became an all-consuming media spectacle last fall, CNN’s Anderson Cooper began regularly drawing on the commentary of a young Dallas Morning News reporter named Seema Yasmin, who also happens to be a physician and a part-time professor of epidemiology at the University of Texas at Dallas.

The Morning News, which has won nine Pulitzer Prizes over the last two decades, had hired her to cover public health issues on a part-time basis a few months earlier. Cambridge-educated, Yasmin arrived at the Morning News via the Munk School’s Fellowship in Global Journalism, which trains people who are experts in a subject – such as health, law or science – to become journalists, and then places them as interns at news organizations. Yasmin had worked with the paper on health features during her fellowship at the Munk School of Global Affairs, and was offered a job soon after graduating. “She was ‘fully loaded’ for Ebola,” says Morning News editor emeritus Bob Mong, noting that Yasmin’s media profile has skyrocketed in the past year. “Without Munk, we would have never known about her.”

The innovative arrangement between U of T’s Munk School and the Morning News is one of nine such relationships the school has struck with media outlets around the world since 2012, and reflects the rapid changes occurring in the news industry. Long-established companies have found themselves under sustained assault from low-cost digital upstarts that have scooped up readers, advertising dollars and investor equity. Ascendant media properties such as BuzzFeed, Genius, Gawker and VICE are growing exponentially – and hiring. Established media brands, meanwhile, have scrambled to retain readers and advertisers in a fragmented media universe.

To complicate matters, the media landscape is now humming with new information formats – from podcasts to data visualizations and “listicles” (lists of facts on a theme). There are other variants, too. For example, “Doctor Mike” Evans, a physician at St. Michael’s Hospital who teaches family medicine and public health at U of T, has created an entirely new type of health journalism in the guise of a popular YouTube channel featuring upbeat whiteboard animations on health topics ranging from exercise to cancer to concussions.

The fluidity of a media environment in which traditional distinctions among print, video and radio have evaporated is forcing journalism programs to make drastic changes in how they train their students, who have no memory of life before search engines. Many schools in the U.S. and Canada have modernized their curricula in recent years. “A lot of journalism educators are trying to figure out what mainstream media organizations want,” says Jeffrey Dvorkin, the director of UTSC’s joint journalism program with Centennial College, and formerly vice-president of news and information at National Public Radio in the U.S. Students, he says, tend to be “way ahead” of the instructors in terms of technical knowledge, and the constantly evolving ways digital media can be used to tell stories.

Centennial journalism professor Tim Doyle, who coordinates the joint program, says the two institutions have recently introduced curriculum changes such as a “digital first” approach to publishing, techniques for telling stories in web-exclusive ways, and training in online audio, live blogging and tweeting.

In Dvorkin’s view, however, the development of core skills – critical thinking, curiosity, news judgment, interviewing and writing – continue to form the foundation of any program. “The role of journalism programs is to help people make sense of a really chaotic media environment,” he adds. “We need to help young journalists do comprehensive, contextual reporting.”

Rob Steiner, director of the Munk Fellowship in Global Journalism and a former Wall Street Journal correspondent, believes the program he founded has identified what media companies are looking for now: enterprising and entrepreneurial journalists who arrive with plenty of expertise instead of an expectation of regular assignments and a full-time job. “They need people with subject-matter knowledge who also have news judgment and can work without necessarily being a staff writer.”

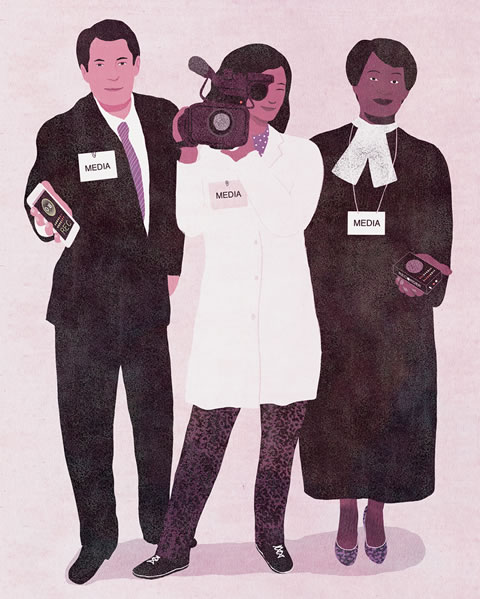

Sarah Elton (BA 1998 UC, MA 1999), a freelance writer who teaches in the Munk program, adds that it remains important to stress ethics (a staple of undergraduate journalism courses) in the program, which is geared toward people from other professional backgrounds. Think of a practicing lawyer who also writes about high-profile court cases; conflicts of interest could arise frequently. “We troubleshoot various situations and talk through all sorts of quandaries,” says Elton, who specializes in health issues. “I think this develops their journalistic acumen.”

Stephen Starr, a 32-year-old Irish-born freelance writer, didn’t set out to become a journalist when he earned a graduate degree in international security and conflict studies in 2007 from the Dublin City University. He simply wanted to go to Syria or Lebanon to look for work. Four years after arriving, he found himself with front-row seats to the civil war that erupted after the Arab Spring. Starr began freelancing full-time and went on to write a book about his experiences, Revolt in Syria. But despite his proximity to a major international story, he sometimes struggled to convince leading news outlets to buy his work. “I knew I was in a great spot but they weren’t as receptive as I had hoped they would be.”

After leaving Syria in 2012, Starr was accepted at Columbia University’s Graduate School of Journalism, but he couldn’t secure sufficient financial aid and opted to enroll in the Munk program instead. In hindsight, he’s glad he made that choice, given the very low student-teacher ratio (his cohort had seven fellows and four instructors) and the opportunity to spend some time in the newsroom of The Globe and Mail, another Munk School media partner.

The program, he says, taught him how to generate story ideas, pitch them to editors effectively and build a freelance practice around his area of expertise. Fellows pitch and report feature stories to Munk’s media partners, but the articles are thoroughly edited by the program’s instructors. The fellows also work closely with beat reporters or bureau chiefs at their assigned media partner.

Since completing the Munk Fellowship in 2013, Starr has stationed himself in Istanbul, and has focused not just on the Middle East but on maritime issues and food security. His journalism career is developing better than he expected, he says, and he’s now in a position to choose what he wants to write about. He’s got clients around the world, including The Guardian. But, he acknowledges, the lifestyle isn’t for everyone. “You need to enjoy the challenge of not knowing whether you’ll get enough assignments to make a living.”

Starr agrees with Steiner’s belief that freelancing – or at least a certain type of freelancing – may represent the future of journalism as a profession. Steiner’s case is built on a reading of the media environment: traditional routes into the profession – such as internships and jobs at small-town papers – are shrinking for young reporters, and full-time, unionized positions are in decline as media organizations fill holes using contract employees.

Steiner believes the fragmented global media landscape has created new reporting opportunities as well as challenges. One way that he believes long-established media companies can differentiate themselves from newcomers such as BuzzFeed and Gawker is with specialized coverage that draws on a reporter’s deep knowledge of a topic. He cites the examples of Clive Thompson (BA 1992 Victoria), a technology writer for Wired and The New York Times Magazine, and New Yorker medical correspondent Atul Gawande, a surgeon and professor of medicine at Harvard. Steiner also points to Elton, whose coverage of food and health has translated into book projects and speaking appearances. In fact, Elton will be starting a PhD at U of T this fall because her coverage took her all the way to the scientific coalface. Original research, she says, “is the natural next step.”

Elton points out that the fellows who come to the Munk School tend to fall into two categories – those with a professional designation who see an opportunity to add journalism to their existing careers, and others who want to work in journalism full-time. “There are great opportunities for the former,” she says, citing the example of a physician in the program who intends to write about health issues and has sufficient technical background not to fall into the trap of breathlessly shilling for the latest health fad. “We need knowledge-based journalism. If you can work as a doctor and a freelancer, that’s the best of both worlds.” Steiner points out a second advantage of being qualified in two fields: “The kinds of people who come into the program have more options for earning a living.”

The reality of how little freelancers get paid can be a big obstacle for writers. For her doctoral research, Nicole Cohen, a professor at the Institute of Communication, Culture, Information and Technology at UTM, conducted an anonymous online survey of working conditions for 200 Canadian freelance journalists. She found that 45 per cent earned less than $20,000 (before tax) from freelance writing in 2009, while only 14 per cent made more than $50,000 – barely a living wage in media hubs such as Toronto and Vancouver.

In a recent journal article, Cohen argues that the economics of freelance journalism have been getting even worse since that study. For this, she blames what she sees as a troubling surge in demand from online publications for freelancers who can churn out stories frequently, often for only a few dollars an article. “Content farms,” she continues, “use algorithms to identify common search queries online, then commission freelance writers and videographers to produce content that will match keyword searches, optimized to appear at the top of search engines.”

Steiner’s vision of freelancing is obviously very different, with its focus on specialists who figure out how to “own” a topic and then use their expertise to sell unique stories to a wide range of global media customers. “This is a very different kind of freelance game,” he says. “We are training people to be leading global journalists.” In the old model, many generalist freelancers would pitch similar stories to a small number of local editors – “a buyer’s market.” Under the Munk School model, the freelancer becomes one of the best writers in the world on a specialized topic, turning the relationship with editors into more of a seller’s market. To that end, Munk fellows learn a rigorous and repeatable approach to idea generation and get a crash course in news judgment. “The basic rule is, ‘always, always be pitching.’”

For many of the Munk fellows, freelance work (as opposed to a staff position) may be just fine. Stephen Starr, who is not angling for a full-time job, says he now can pick and choose his freelance assignments and has as much work as he wants. Nousha Kabawat, a recent Munk fellow who runs an NGO focused on helping Syrian refugees, sought out the journalism training so she could better communicate information about the human face of the Syrian conflict, and also offer advice to Syrian humanitarian relief workers on how to win the attention of Western reporters. During the program, she published a detailed, eyewitness account in the Deseret News, a Munk School partner. Yet, she adds, “I definitely don’t see myself doing journalism full-time. I learned it’s really hard to be a journalist, especially a freelancer.”

On the other hand, some other Munk fellows – Anna Nicolaou at the Financial Times, and Rachel Browne at Maclean’s – have landed in media organizations upon graduating, despite the program’s focus on freelancing. The reasons aren’t difficult to fathom. Editors such as Bob Mong are seeking ambitious journalists with deep subject expertise who also know how to pitch stories, generate ideas and take the initiative instead of waiting for assignments. As he says of Seema Yasmin, the prospect of hiring a reporter with this mix of skills “was very appealing to us.”

Note: An earlier version of this story incorrectly identified Jeffrey Dvorkin as a former producer at NPR.

No Responses to “ Breaking News ”

We need writers to help persons who are dying to 'die wise,' and to help their families who are part of the now-prolonged dying process. I am a senior with a history of various types of cancer. The medical system has prolonged the process of dying to the point that we are unable to pay for the resulting health-care costs. Perhaps we should refocus our energy toward the whole person and family rather than on what medical technology can do to preserve the body. I am reading Stephen Jenkinson's Die Wise: A Manifesto for Sanity and Soul. It's a beauty!

I read this article with great interest, but author John Lorinc left out one major lesson: Never sell your work only once, or you'll go broke.

I was in the Ottawa Parliamentary Press Gallery working for the Toronto Telegram when that paper ceased publication in October, 1971. I had three teenage kids, a wife who didn't work outside the home and no job. I remembered advice I received in the early 1960s from freelance American photographer Larry Schiller, who told me you had to sell the same piece of work to many different customers to make a decent living freelancing. When the Telegram folded, I set up a network of half-a-dozen large American newspapers, a chain of 10 papers in South Africa, the Sunday Times in London, and regular broadcasts to a series of local CBC stations. They all bought basically the same material. I doubled my income in the first year, loved working 70 hours a week, and loved even more the fact that I never again had to do something stupid. Budding freelancers must realize that selling the same work to multiple customers is the key to success -- and make sure each customer knows who the others are.

Peter Ward

Southam Fellow, Massey College, 1967

Thank you, Peter. That was very well said. I think the Internet has definitely made it a much more competitive field -- you need to pitch and you need to do it fast, but when it comes down to it -- it's who you know. Keeping in touch with your network of editors and media associates is important. Some things never change.