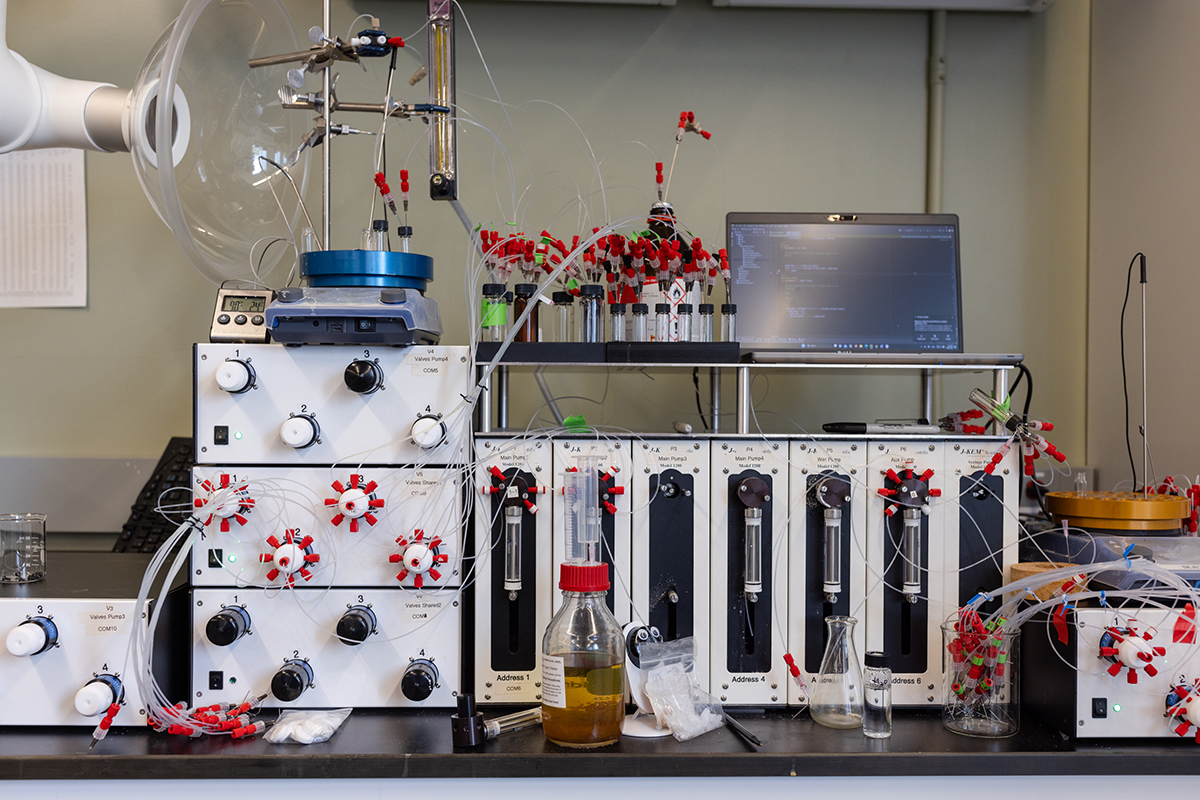

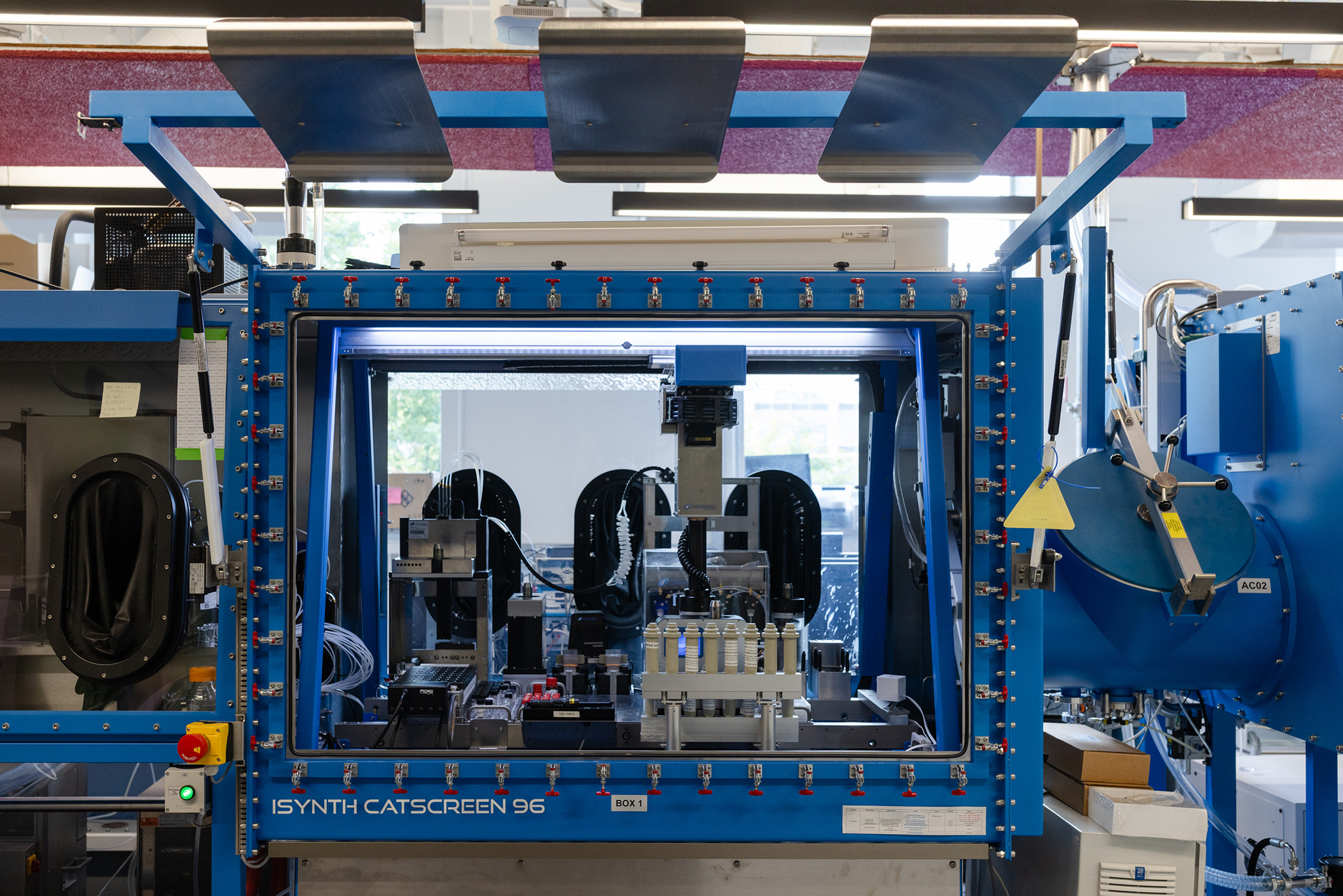

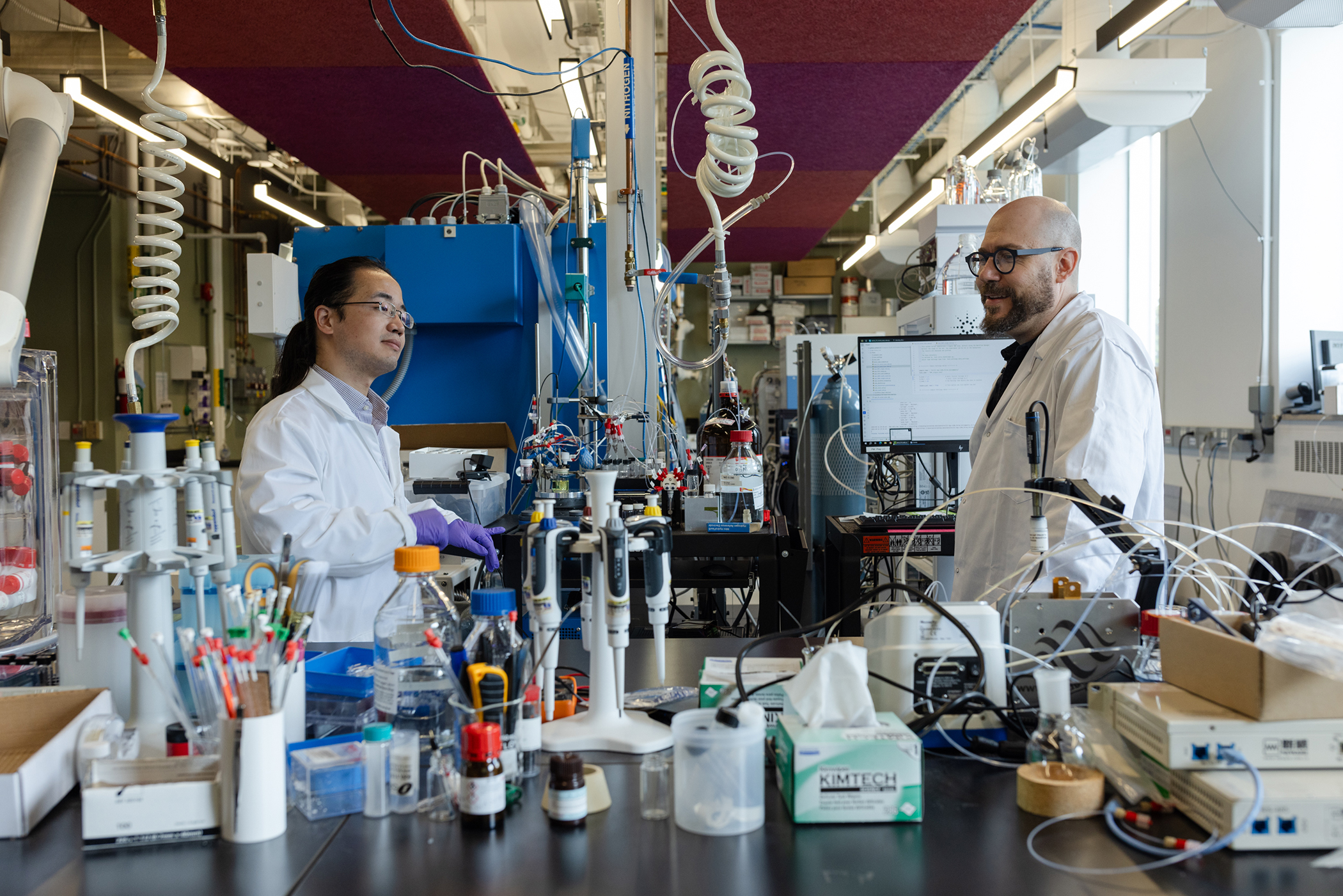

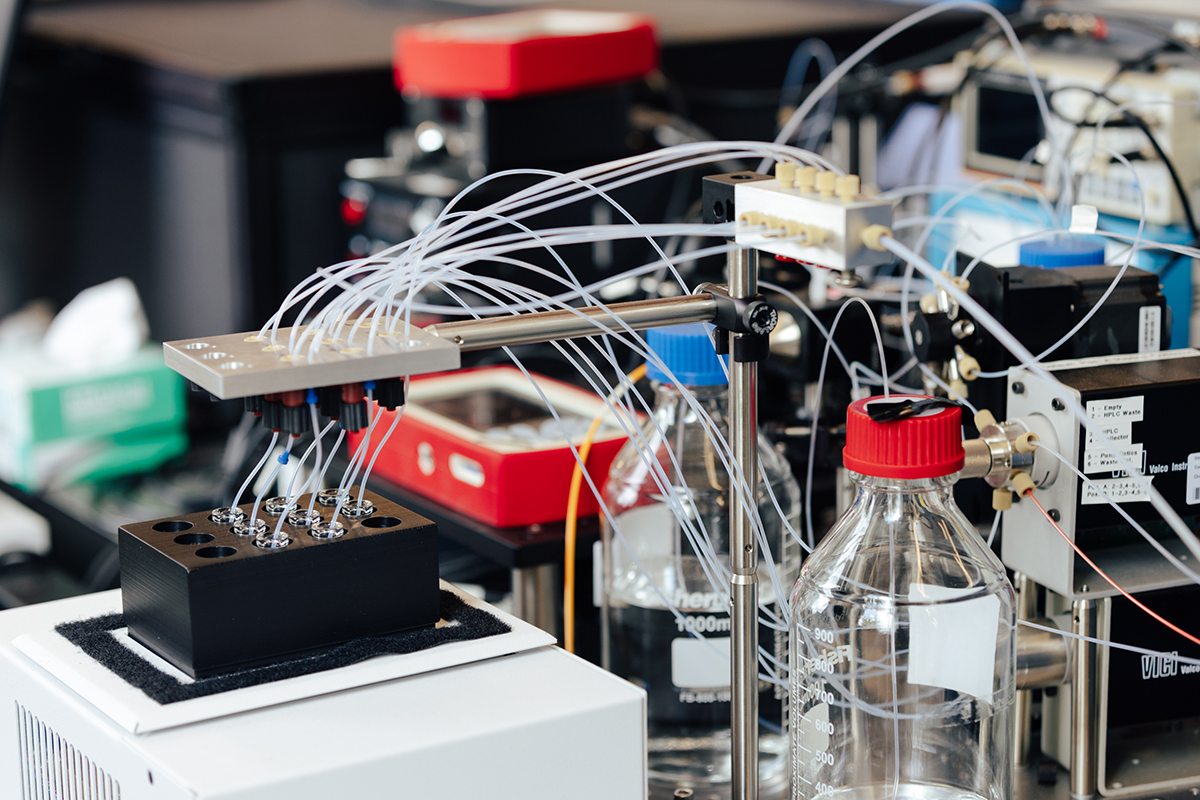

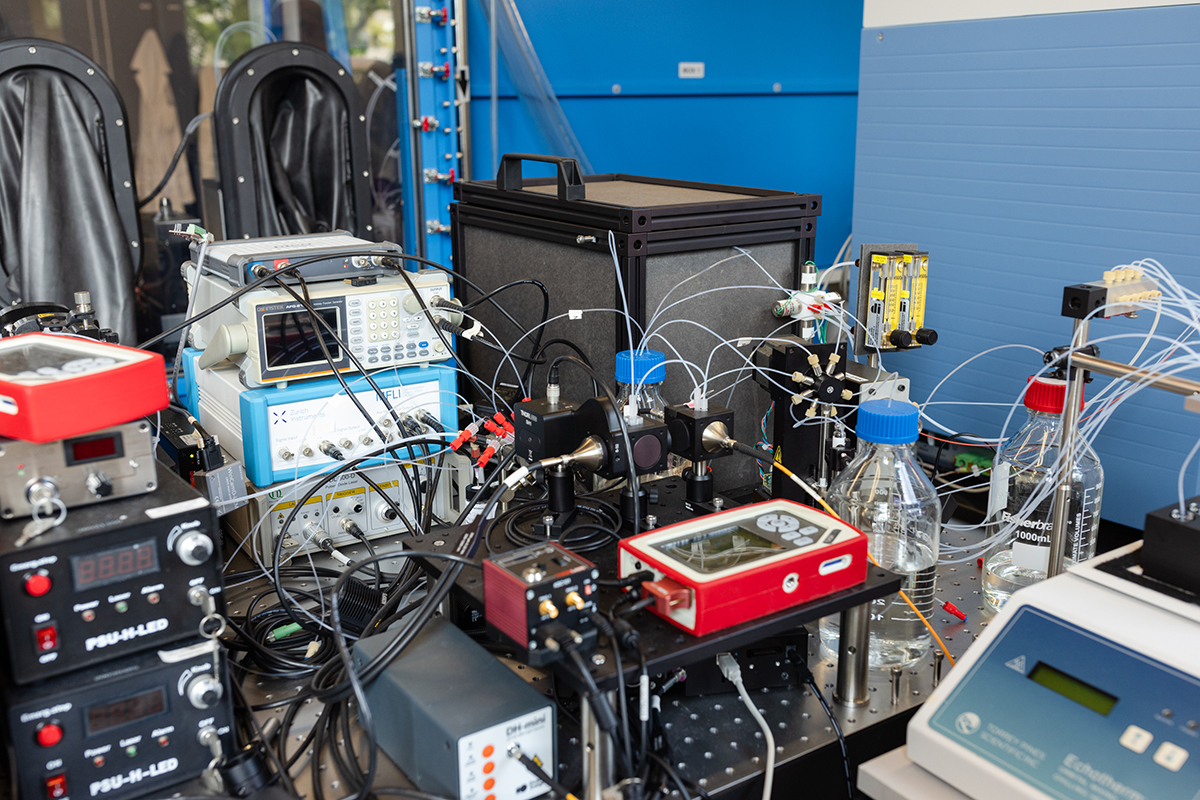

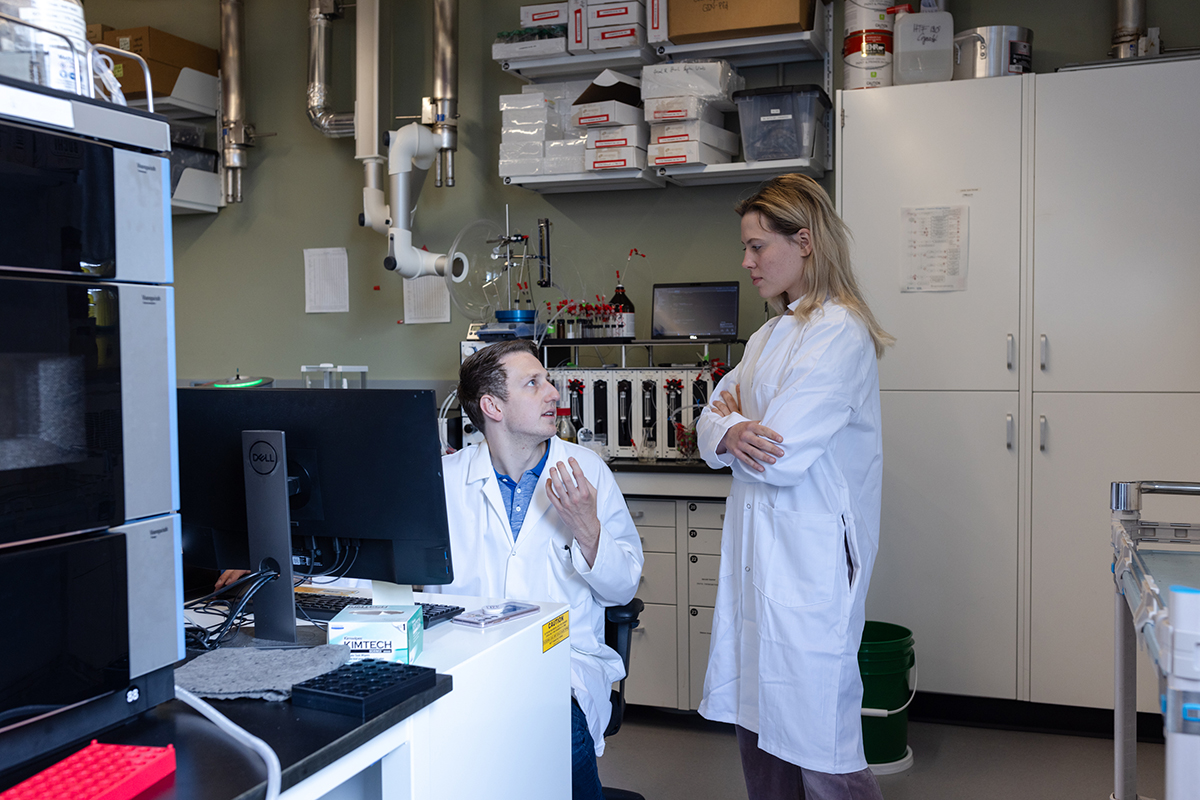

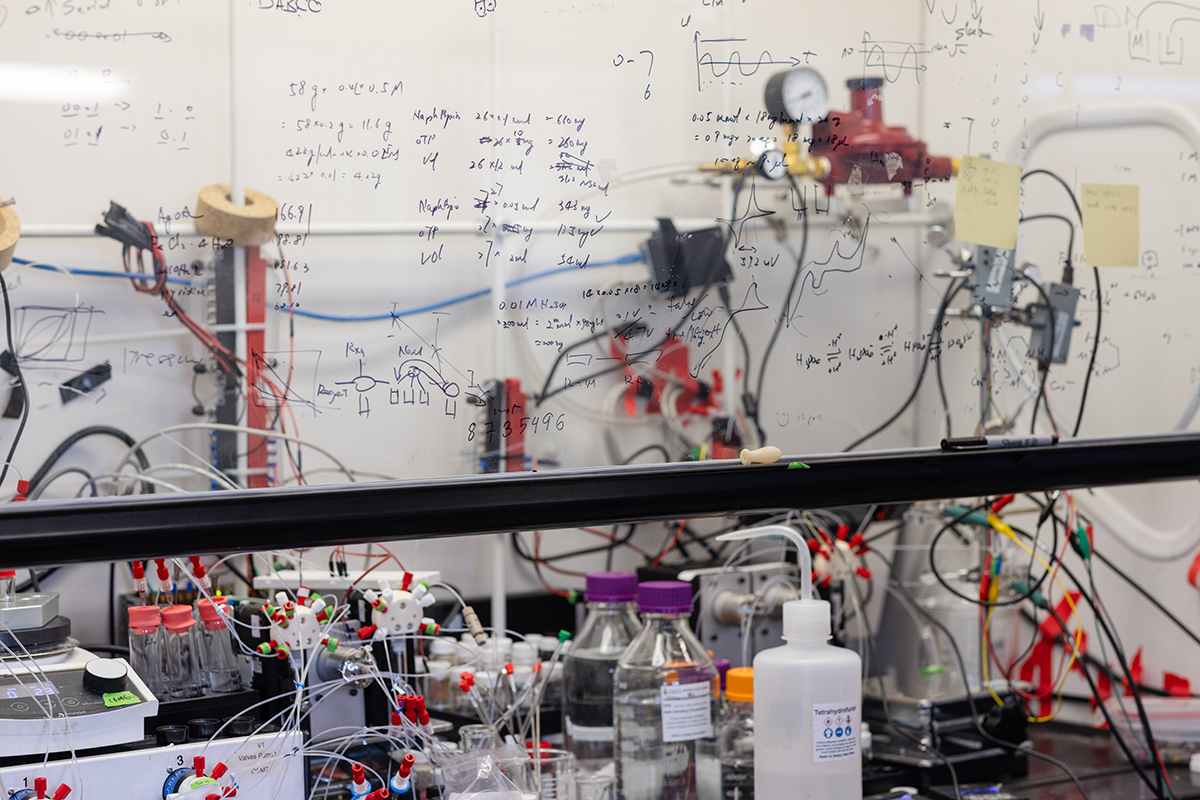

In this University of Toronto chemistry lab, robots do 90 per cent of the manual work. There is still a lab manager to oversee operations but almost all of the most tedious, repetitive tasks are handled by machines. AI, meanwhile, is helping scientists choose experiments to yield the greatest chance of success, allowing them to focus on bigger questions.

This “self-driving lab” belongs to U of T’s Acceleration Consortium, a two-year-old network of nearly 100 researchers around the world that is using AI and automation to radically shorten the time it takes to discover new materials. Earlier this year, the group received a $200-million federal research grant – the largest ever to a university in Canada.

The consortium’s director, Alán Aspuru-Guzik, says the group already has proof their approach works. Scientists here took just two months to test the efficacy of more than 1,000 molecules for use in organic lasers, identifying two with state-of-the art performance. (Other researchers have taken as long as five years to test 10 molecules.)

Organic lasers are cheaper to produce than conventional lasers, easier to modify and more environmentally friendly. “We’re essentially supercharging the process of scientific discovery,” says Aspuru-Guzik.