Four ideas out of 23 for building an even better Toronto

Make our streets more pedestrian-friendly.

Walking is more pleasant – and a lot more common – in Toronto’s downtown neighbourhoods than it is in the suburbs. As geographer and planner Paul Hess points out, the blocks downtown are smaller, so people have lots of route choices, and there tends to be a greater variety of destinations. And yet many suburbanites walk in their neighbourhoods, despite the inferior conditions. Is it because they don’t have other ways to get around? And if so, what could the city do to improve walking conditions?

Hess is conducting research to find out. His team has been speaking with bus users along Finch West and Sheppard East, asking them how far they walk to reach transit and what they think of the experience. The researchers will also be conducting “walking interviews” with pedestrians in those areas to determine what they like and dislike about their route and what they would like to see improved.

The results will be fed to the city and to regional transit authority Metrolinx to consider as they plan transit upgrades in Scarborough and North York.

Boost suburban cycling to downtown levels.

The downtown core currently accounts for 80 per cent of bike trips in the Toronto area, but Trudy Ledsham, project manager for U of T’s Cycling Think & Do Tank at the School of the Environment, sees potential to boost the popularity of cycling in the suburbs.

Earlier this year, her group teamed up with the Toronto Centre for Active Transportation and the Region of Peel to lead Pedalwise, a community bicycle program in Brampton, Ontario, that pairs new cyclists with mentors, lends them bicycles for the summer and provides safe cycling workshops, demonstrations of how to use bike racks on buses, route-planning assistance and group rides organized by volunteers. The program is designed to provide members of the community with basic cycling skills and to boost their confidence on a bike, while promoting healthy living and cycling as a fun activity.

Bike lanes and other improvements to cycling safety are crucial to get people out of their cars and onto bikes, but Ledsham says another important factor is psychological: getting people to change ingrained habits; hence the group’s focus on altering behaviour. “Research shows that people are interested in cycling for transportation,” says Ledsham. “But sometimes you have to show them they can do it.”

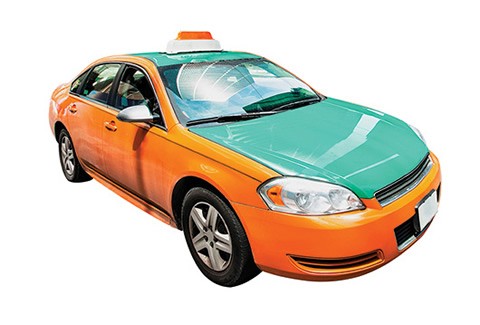

Find a way for Uber and taxis to co-exist.

In Toronto, the battle between traditional taxi companies and ride-sharing services such as Uber is often portrayed as a failure of the old to accommodate the new. The taxi industry refused to modernize. City regulations were written for a world without smartphones.

The tech-driven Uber operates in a legal grey area, negotiating privacy and safety issues on the fly. But a defining issue in this battle might actually be much more straightforward. “The big policy question for Toronto City Council is whether it is in the public interest to limit the number of cabs in Toronto,” says Sunil Johal, policy director at U of T’s Mowat Centre. “Once that question is determined, other issues around insurance and driver training are relatively straightforward.”

He says the city should adopt a similar approach for taxis as it has for restaurants – place no limits on the number of operators, regulate minimum standards and then let the market sort out supply and demand.

“Uber offers a more technologically adept service in terms of electronic payment, rating your driver and being able to track how close the car is before it comes to pick you up,” he says. “But a big part of their disruption has certainly been calling into question what the right supply of cabs in a city should be – and whether having people who only drive between five and 10 hours a week is a good bridging measure to meet demand for taxis when it’s highest.”

Invest in light rail transit in Scarborough, not a subway.

In Toronto, suburban subway-line proposals are built on the promise of sparking a wave of increased urban density and development. But in Scarborough, there are many locations where that density will likely never come.

In Toronto, suburban subway-line proposals are built on the promise of sparking a wave of increased urban density and development. But in Scarborough, there are many locations where that density will likely never come.

“Toronto’s suburban areas were very carefully designed to be difficult to change. They are frozen by design, by regulations and by the expectations of residents and home-owners,” says Andre Sorensen, a professor of urban geography at UTSC. “It does not make sense to build subways in areas where it will be extremely difficult to develop the high density required to justify the cost of building and running a subway.”

Working to transcend the city’s highly politicized transit debate, Sorensen evaluated the three major transit plans presented by the city’s most recent mayors: “Smart Track,” John Tory’s electric train proposal; Rob Ford’s Scarborough Subway; and David Miller’s light rail network, known as “Transit City.”

“The Transit City proposal far outperformed either of the others on all measures,” says Sorensen. “LRT lines on the east-west arterial roads in Scarborough – particularly Eglinton and Sheppard – would create excellent opportunities for gradual intensification while providing greatly enhanced mobility at a much lower cost,” he notes.

He says Transit City would also protect existing residential neighbourhoods, as development would primarily face the arterial roads adjacent to the LRT lines.

See how U of T students, faculty and researchers are helping to make Toronto a more:

Diverse and Inclusive City