It would come to be known as the Voyage of the Damned. Months before the start of the Second World War, the German ocean liner MS St. Louis, with more than 900 Jewish refugees aboard, sailed aimlessly across the narrow straits that separate Cuba and Florida, as Jewish leaders in the United States frantically worked to secure a hospitable port of entry. “So near, and yet so far,” remarked one of the passengers, as she gazed out at the Florida coastline.

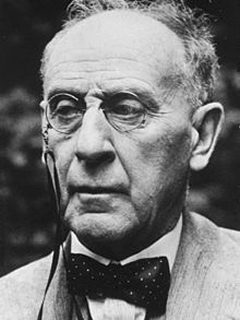

News of the plight of the St. Louis and her passengers reached the University of Toronto and touched influential members of the campus community. History professor George Wrong led a group of prominent U of T academics, social activists and clergy in petitioning Prime Minister William Lyon Mackenzie King to admit the Jewish refugees into Canada on humanitarian grounds. “We the undersigned, as Christian citizens of Canada, respectfully suggest that…you forthwith offer the 907 homeless exiles on board …Sanctuary in Canada,” read the telegram dated June 7, 1939.

The message was signed by 41 additional Canadians, nearly all of whom claimed close ties to the University of Toronto, including former president Robert Falconer; Malcolm Wallace, principal of University College; B.K. Sandwell, an alumnus and editor of Saturday Night.

In November 1938, the brutal events of Kristallnacht (the Night of Broken Glass) – a wave of violent attacks on synagogues, homes and Jewish-owned businesses – prompted hundreds of thousands of Jews to seek escape from Europe. The flood of emigrants created an international refugee crisis and, in response, delegates from 32 countries convened in Evian, France, in July 1938 to discuss the issue. While many delegates expressed their nation’s sympathy for the Jewish people, most countries, including the United States and Canada, offered little more than excuses for why they could not take in more refugees.

It was in this atmosphere that, in the spring of 1939, the St. Louis and her passengers departed Hamburg, bound for Havana. Although nearly everyone on board held landing certificates and transit visas, all but approximately two dozen of the men, women and children were denied entry by the Cuban government. Increasingly desperate, Jewish organizations appealed in vain to the governments of Argentina, Uruguay, Paraguay and Panama to grant the refugees asylum. The passengers’ final hope lay with the United States and Canada. Telegrams and cables to President Roosevelt fell on deaf ears as the St. Louis sailed up the Florida coast. Wrong’s telegram received a similarly chilly reception from the prime minister. King believed the refugees were not Canada’s problem, but nevertheless asked his top advisers to consider Wrong’s request. The director of immigration reported that none of the St. Louis passengers qualified to enter Canada.

And so, despite the pleas of Prof. Wrong and his U of T colleagues, just two days from the safety of Halifax Harbour, the St. Louis was forced to return to Europe, where at the last minute Great Britain, France, Belgium and Holland were persuaded to take the refugees in. Over the next several years, as Nazi Germany laid claim to great swaths of the European continent, only those who had the fortune of disembarking in England would escape persecution. By war’s end, nearly one third of St. Louis passengers had perished in concentration camps.

Over the course of the war, Wrong, Falconer, Wallace and other members of the U of T community continued to work on behalf of Jewish refugees. “Although it was never enough, U of T did quite a bit to try to help,” says Paul Stortz (PhD 2006) a historian of 20th-century Canadian immigration and universities and the author of a study about refugee professors at the University of Toronto. “U of T president Henry Cody was a strong Jewish ally and under his leadership, the university helped focus attention on the plight of European Jews, took in Jewish students and hired a number of displaced academics.”

In the spring of 1939, William Stewart Wallace – a professor of English and history and university librarian – led a small group of U of T academics to organize the Canadian Society for the Protection of Science and Learning, which sought to bring refugee intellectuals to the University of Toronto and other Canadian universities. Throughout the 1930s and 1940s, U of T received urgent letters from Jewish academics describing the increasingly desperate and dangerous conditions in Germany and other parts of occupied Europe. “I have lost my position as a professor of Modern History at the [University of Vienna]…” wrote Professor Dr. Friedrich Engel-Janosi to Wrong. “I am not allowed to use any archives and libraries in Germany any longer. So it is impossible for me to continue my scientific work and earn my livelihood there.” The letter goes on to ask whether there might be an opening for him at the University of Toronto.

According to Stortz’s study, between 1935 and 1945 the university hired 20 refugee European lecturers and professors (Prof. Engel-Janosi was not among them), at least half of whom were Jewish.

In recent weeks, debate about treatment of Syrian refugees has put the spotlight back on the St. Louis and the fate of her passengers. While no historical parallel is perfect, many have noted similarities between debates over admitting Jewish refugees in the 1930s and ’40s and those being had about Syrian refugees today.

“The St. Louis was a horrible tragedy that can be seen as a kind of cautionary tale about what can happen when refugees are turned away,” says Stortz. “It demonstrates how important it is for governments to act fast and decisively in response to international refugee crises.”

No Responses to “ Seeking Refuge from Nazi Persecution, the MS St. Louis Was Turned Away at Every Port ”

An excellent article on our history that I would assume is not common knowledge. We Canadians do not know our history as well as we should. I just read an excellent article in the Globe and Mail about MacKenzie King. This one action of refusing these people must have or should have been a grave error in judgment. No one person gets it right all the time but we must always strive to do better. Thank you for your coverage.