For his 2002 history of the University of Toronto, Martin Friedland researched the contributions that U of T alumni made to the Allied cause in the two world wars. Among the 630 students and grads who died in the First World War and the 557 in the Second, one particularly affected Friedland. “Maybe because law is also my field, the loss of this promising young lawyer, J.K. Macalister, stood out for me,” says the former dean of U of T’s law school. “There was something about the photographs of him. And then what I learned about his story intrigued – and horrified – me. I still get a bit shaken when I think of him.”

The briefest description of John Kenneth Macalister’s attainments illustrates the promise Friedland saw. After graduating at the top of his law class at U of T, Macalister attended Oxford on a Rhodes Scholarship. He graduated from there with first-class honours, and went on to the bar exams in London where he placed tops in the empire. When war broke out, Macalister signed up with the Field Security Wing of the British Intelligence Corps. After Continental Europe’s rapid fall, he enlisted with a new intelligence service, the Special Operations Executive, which had been set up to foment resistance in German-occupied territories.

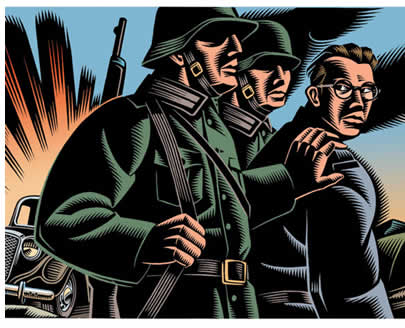

“Set Europe ablaze,” instructed Winston Churchill. After a hasty training in spy-craft, the French-speaking Macalister was parachuted into the Loire Valley in 1943. Unfortunately, before he could set his little bit of the continent on fire, the Gestapo captured and imprisoned him. In the war’s final days, a panicked Hitler ordered the execution of captive spies, such as Macalister, to prevent them from describing their appalling treatment. After hanging Macalister and 15 other captives in the bowels of Buchenwald – with piano wire attached to meat-hooks – the SS guards cremated the remains. It was Hitler’s aim to keep their fates a secret. In Macalister’s case, the führer and his minions failed. The Nazis disposed of his body, but they couldn’t destroy his story.

At the top of the J.K. Macalister file the University of Toronto Archives is a clipping from an April 1945 edition of the Guelph Mercury – one which, despite its understated language, wields a wallop. “Notification has been received from the British War Office by A.M. Macalister, editor of The Mercury, and Mrs. Macalister… [residing on Metcalfe Street], of the death of their son Capt. John Kenneth Macalister on September 14, 1944. The parents had been notified previously that their only son had been missing in June.”

“The Macalisters sort of disappeared from Guelph after his death,” a high school friend, George Hindley, recalls during an interview from his home on the same sleepy, tree-lined street where the Macalisters once lived. “As far as I know, he was the last of that whole line.”

In high school, Macalister was a strong, but not stellar, student. In addition to history, he particularly enjoyed French – and the stylish, lively French teacher, Olive Freeman (who went on to marry John Diefenbaker and frequently sported Chanel at otherwise dowdy Ottawa events). Hindley, a top student, recalls: “You knew Ken was smart, but you didn’t suspect in high school that he’d be able to compete with the best in the province – let alone at Oxford.”

In 1933, the pair went off to U of T with many of the province’s best, Hindley to study classics at Victoria College, Macalister to study law at University College. “We didn’t see much of each other, being at different colleges,” Hindley says. “But I did appreciate him taking me out to dinner once early on. I was 16, a farm boy; he was a little older, more sophisticated, the son of a newspaper editor.”

In addition to excelling at his studies, Macalister threw himself into the extracurricular life of the university, joining the UC Literary and Athletic Society, playing rugby, debating at Hart House, serving as chief justice of the moot court, and chatting en français with the French Club. A working knowledge of French was viewed as helpful for English Canadians interested in entering politics – Macalister’s ultimate ambition.

In 1937, Macalister boarded a steamer and embarked on the month-long journey to the U.K. to register in law at Oxford’s venerable New College. The small-town Ontario boy didn’t let the grandness of the stage affect the quality of his performance; he earned excellent grades in his first two years. In the summer break of 1939, still hoping to polish his French, he went to live with a family in Lisieux, Normandy. The daughter of the house, Jeannine Lucas, captivated him and, by the end of the summer, they married. Theirs was a brief idyll: in September, Germany sent its tanks into Poland, and Europe again found itself at war.

Macalister tried to sign up for the French military, but his nearsightedness disqualified him. He decided to return to England. When he left his wife with her family in France, they didn’t suspect that she was pregnant – or that the war would irrevocably divide them. It was an emotional time, a time of swift unions and equally quick, unintentionally final partings.

Back in Oxford, the armed forces’ recruiting board turned down Macalister’s application to join the military (again because of his poor eyesight) and encouraged him to complete his studies. He did so, graduating in spring 1940 with a first in jurisprudence, though any celebrations would have been cut short. In April, he received heartbreaking news from France: Jeannine had given birth to a stillborn daughter – their daughter.

He carried on with his studies. At the bar exams that year, he came first among the 142 from across the empire who sat the tests. Unsure what to do next, he contemplated returning to Canada. Hart Clark, another Canadian Rhodes Scholar at Oxford reported that it was unclear whether Canadians in Britain should enlist in Canada or England. Macalister wrote to a former U of T prof of his, W.P.M. Kennedy, to let him know he was at loose ends. The professor at once wrote back, offering Macalister a faculty job, but it was too late. “In army since yesterday,” the young man telegraphed Kennedy in September 1940. “Sorry. Many thanks.”

***

After the fall of Norway, Denmark, Belgium, Holland, France and much of Eastern Europe, the British war cabinet decided in July 1940 to set up an agency to encourage resistance – through sabotage and propaganda – in Axis-occupied territories. The Special Operations Executive (SOE) – that Macalister joined midway through the war – was like something out of a John le Carré novel. It was typically headed by a knighted Whitehall insider, known in the organization simply as CD. A bunch of Old Boys were appointed to run it.

Potential recruits met Selwyn Jepson, the SOE’s recruiting officer, in a stripped-down room at London’s Northumberland Hotel. Interviewing half in French and half in English, Jepson was looking for reflective men and women, not impetuous sorts. He told potential recruits that there was a one in two chance they’d die in the service – and told them to sleep on it before opting in or out. “I don’t want you to make up your mind too easily,” he is reported to have said. “It’s a life-and-death decision.”

In mid 1942, Macalister opted in and began five months of gruelling training across Britain. The recruits learned parachuting near Manchester and railway sabotage (using real locomotives) and firearm handling on Scotland’s northwest coast. At Beaulieu Manor near lush New Forest, ex-Shanghai police officers instructed them in methods of resisting interrogation and torture, and in ju-jitsu (so they could kill silently). Only about one in five who began the rigorous course completed it. Macalister’s instructors rated him highly. “Quiet and reserved, but with plenty of acumen,” one wrote. “He gives the impression of easy-going urbanity, while in reality he has a particularly tough scholar’s mind, logical and uncompromising in analysis.”

In the Scottish segment, the would-be spies had to choose a mission-mate, and Macalister and a fellow Canadian, Frank Pickersgill, banded together. A tall, genial Winnipegger who’d completed a master’s in classics at U of T, Pickersgill had already escaped once from the Nazis. Before the war, in Paris, where he knew existentialist philosopher Jean-Paul Sartre, the freelance journalist didn’t believe France would fall as quickly as it did and didn’t get out in time. Just north of Paris, the Germans imprisoned Pickersgill as an enemy alien, but, with a metal file smuggled to him in a loaf of bread, he sawed his way out of his cell and escaped. With help from expatriate American writer Gertrude Stein, he fled to neutral Portugal and then shipped out to England.

Back with Macalister, Pickersgill was about to head back into the fray. The pair’s superiors decided the Canadian duo would parachute into occupied France in June 1943, but, in the interim, awarded them a long leave in London. Here they fell in with a friend of Pickersgill’s from the University of Manitoba, Kay Moore, who was working with the Free French Intelligence Service, and her Canadian housemate, Alison Grant, who was employed by MI5, the British security service. Despite the Blitz and the daunting mission in the offing, the foursome enjoyed a giddy romp, drinking tea and talking with each other and the many Canadians who frequented the girls’ Belgravia townhouse. (So many Canadians visited the home that it became known as the Canada House Annex.) They spent their nights dancing at the Palais Royale or going to the cinema.

As quickly as Macalister had fallen for his French wife, Pickersgill tumbled for the remarkable Grant – a witty, attractive woman from an intellectual Scottish-Canadian family (her brother was the philosopher George Grant). She and Pickersgill agreed that if they survived the war, they’d get engaged, but who knew what would happen? They started planning the mission in France. It was important that Macalister and Pickersgill look like migrant nobodies after their drop, so Grant went with them to a down-market clothing store, bought coats and ripped the linings out. To make their clothes look older, they rubbed them in dirt. “It was all very amateurish, I suppose,” Grant said later.

***

After the war, some historians accused the SOE of operating inexpertly, arguing that it was run by a bunch of bumbling upper-crust twits. No less an authority than American General Dwight D. Eisenhower, however, said the fledgling agency’s efforts shortened the war by months. Certainly, though, the spymasters could have done a better job of planning the young Canadians’ mission.

A few days before the drop was scheduled for the Loire Valley near Romorantin, the British parachuted explosives into the same region (to be used in sabotage), but the explosives went off when they hit the ground. More than 2,000 German soldiers poured into the area to investigate. The SOE’s agent on the ground, Pierre Culioli, radioed London: Abort.

It’s unclear whether the message got through. London went ahead with the mission (code name: Archdeacon), dropping Macalister (French code name: Valentin) and Pickersgill (Bertrand) in the woods on the moonlit night of June 15, 1943. Here they were met by Culioli and Yvonne Rudellat, one of the SOE’s first female field agents. The plan was that Macalister and Pickersgill would lie low for a couple of days in the summer home of the pro-Resistance mayor of Romorantin, and then Culioli and Rudellat would drive them to a Paris-bound train. There, in the Gare d’Austerlitz, they would meet up with another agent who would help them get to the Sedan region, northeast of Paris, where they were to set up a network of spies and saboteurs.

The mayor’s son, Jean Charmaison, wrote a letter to Pickersgill’s brother about the surprisingly free ranging conversations he had with the young soldier-scholars. “We had long discussions under an oak tree – about science, art, literature, philosophy, while, time and again, German planes flew over at treetop level,” he recalls. “Macalister was more of a talker and had a rather deep voice. He also had a limp… caused by a sprain he suffered on landing by parachute.”

On June 21, Culioli and Rudellat picked up the pair, intending to drive them to a train station a few towns away. They passed one German security checkpoint, but at another, in the hamlet of Dhuison, the men in the back seat were ordered out of the car and marched into the town hall for questioning. Culioli and Rudellat’s papers and cover stories passed muster, so they waited nervously in the car out front for the Canadians to re-emerge.

When, instead, a Gestapo agent came out and approached the car, Culioli tore off. After a high-speed chase, during which the German soldiers managed to shoot the passenger Rudellat in the head, Culioli deliberately crashed his Citroën into a wall, hoping it would catch fire and that the trunk’s incriminating contents would be consumed. It didn’t ignite, and the Germans found two radios, several letters addressed to undercover field agents in plain English – SOE’s error – and the codes the pair were to use in radio communications with London. Contrary to orders, Macalister had written down the security checks – a breach of policy that had dire consequences.

No one quite knows how the Germans initially saw through the Canadians. Commander Forest Yeo-Thomas, an SOE agent imprisoned with them, claims it was Macalister’s sub-par French; despite all the French lessons and his marriage to a Frenchwoman, his accent “was so faulty,” the agent claimed, “that they could never hope to pass themselves off.” Others point to a mole in the SOE’s network who may have tipped off the Germans about the pair’s imminent arrival. Either way, Macalister would spend the rest of his short life in Nazi-run prisons.

***

In possession of Macalister’s radio and codes, the Gestapo duped the Brits into sending, over a 10-month period, 15 munition drops and more than a dozen agents, all of whom were immediately imprisoned. Hitler is reported to have been jubilant.

The Canadians, meanwhile, were moved from a prison in Blois to Fresnes, a dank, 19th century fortress-like prison on the southern outskirts of Paris. (On the wall of a cell is carved “Pickersgill, Canadian Army Officer.”) Their captors tortured them. After the war, fellow captive Yeo-Thomas matter-of-factly reported, “Pick and Mac were given the usual beating up, rubber truncheons, electric shocks, kicks in the genitals. They were in possession of names, addresses and codes that the Germans badly wanted, but neither of them squealed.” Both repeated what they’d been told to say: “I demand that you notify my family of the circumstances of my arrest.” Pickersgill was shipped off to a prison in Poland (Macalister is believed to have been sent with him), then recalled to Paris for help in the ongoing effort to fool the SOE.

The Nazis wined and dined Pickersgill at the Gestapo’s Paris headquarters in an effort to persuade him to assist them. Their implied message: if you co-operate, all this can be yours. Pickersgill didn’t relent. Instead, he broke a wine bottle, used the jagged edge to slit a guard’s throat and managed to escape by jumping out a second-storey window. The SS gunned him down in the street and imprisoned him again.

After several months, the British began to doubt whether the radio messages emanating from the so-called Canadian circuit were genuine. They sent a message they knew the pair would understand: “The samovar is still bubbling at 54A.” This was the address of Moore and Grant’s London home where they had consumed so much tea. The Germans’ response, “Happy Christmas to all,” was too vague; it didn’t sound like Macalister or Pickersgill. This was one of the clues that led the British to conclude (after a few more months) that the radio messages were phony. Too late for the agents already served up to the Nazis, the SOE discovered their error.

They had lost an intelligence battle, but the Allies were starting to win the war. After D-Day, the Germans shipped the spies to Buchenwald, the notorious concentration camp in southeast Germany. Handcuffed back-to-back in pairs, 37 captured spies were crammed into two seatless boxcars for an eight-day journey. At Buchenwald, Yeo-Thomas remembers Pickersgill and Macalister discussing Picasso, ragtime music, cartoons, Mozart, Westerns and Shakespeare and singing “It’s a Long Way to Tipperary” and “Alouette” to keep their spirits up. The body is more easily imprisoned than the mind. Sometime between September 9 and 14, 1944, as the Allies closed in, the Nazis executed Macalister, Pickersgill and 14 of their comrades.

The executions were ordered in a last-ditch effort to expunge the pair from history, but the opposite happened. Several of the Canadians’ fellow inmates survived, and through them, their story has emerged. At every stage of Macalister’s journey he is remembered. In Guelph, there’s a park named after him with a maple representing his time in Canada, an oak his British sojourn and a linden his time in France. At U of T’s Soldiers’ Tower, both Macalister and Pickersgill are listed among the lost, and there’s a garden nearby in their joint honour. On the war memorial in Rhodes House at Oxford, on a plaque at Beaulieu Manor in the New Forest, on the cenotaph at Romorantin, near where they parachuted down – on each Macalister’s name is carved. In 1995, the former principal of University College, Douglas LePan published an epic poem on the man, Macalister or Dying in the Dark.

Pickersgill’s great amour, Alison Grant went on to marry diplomat George Ignatieff and became the mother of two boys, Michael, the writer and politician, and Andrew, the executive director of an organization advocating for peace in Israel and Palestine.

“Frank was so right for her,” says Andrew Ignatieff. “Though she went on to live a very full life, she never got over her relationship with Frank. However, she never spoke of him. She always wore a bracelet that I’m pretty sure Frank had given her.

“‘There are some things a mother can’t even share with her son,’ she said when I asked [her about Pickersgill]. Even when she had Alzheimer’s and seemed to have forgotten almost everything, she had to have that bracelet on her.” Recently, when I interviewed Andrew in a Starbucks in Toronto, he held up his wrist. There, welded to a silver cuff, was his late mother’s fragile bracelet.

Jeannine Macalister never remarried, but did become a social worker in Paris. In 1981, she wrote a committee of John Kenneth’s high school classmates in Guelph – Hindley among them – to thank them for setting up a scholarship at Guelph Collegiate Vocational Institute in her husband’s name. “I have been deeply touched,” she writes in her rudimentary English, “by all his friends did to keep alive my husband’s memory.”

Alec Scott (LLB 1994) is a writer in Toronto.

No Responses to “ Behind Enemy Lines ”

I won the J.K. Macalister scholarship at Guelph Collegiate Vocational Institute. Like Macalister, I also went on to U of T. However, unlike him, I subsequently returned to Guelph and lived near the park named in his honour. Although I knew the bare bones of his story I was interested to learn more.

Angela Hofstra

BScPhm 1986, PharmD 1993

Guelph, Ontario

I always enjoy reading U of T Magazine, but the Autumn 2007 issue was particularly good. The articles “Witness to War,” by Stacey Gibson, and “Behind Enemy Lines,” by Alec Scott, were both extremely interesting. When I attended the University of Toronto, I often walked past Soldiers’ Tower but didn’t think too much about it. After reading the story about J.K. Macalister and Frank Pickersgill and their capture by the Nazis in the Second World War, I would like to learn more about the individuals who gave their lives for our country.

Linda Klassen

PharmD 1995

Saskatoon

I was intrigued to see the letters concerning Kenneth Macalister and Frank Pickersgill. Readers will be interested to know that I am publishing A Glorious Mission: The Secret Wars of Ken Macalister and Frank Pickersgill in fall 2008 under my imprint at HarperCollins Canada. Their remarkable story is told in full for the first time by the award-winning historian Jonathan Vance and will add to our appreciation of these two young heroes. Every time I pass the Soldiers’ Tower I think of them.

Phyllis Bruce

MA 1967

Toronto

[...] bad French to discover the spies. Only days before the men were dropped in France, a preparatory drop of explosives had been made. The explosives went off upon landing, and about 2,000 German soldiers “poured into the area to [...]