I first heard of “in vitro” meat – the sci-fi-like idea that steaks could, one day, be grown outside of an animal – as an undergrad in cell biology at the University of Alberta in 2009.

The concept intrigued me. I became interested in studying meat, which has so many issues. Not only is it at the centre of culinary criticism and praise (“Too tough!” “So tender!”), it is debated in discussions of ethics, microbiology, religion, physiology and economics. I decided to take a course outside of the typical cell biology stream: meat science, offered through the agriculture department. It was there I was introduced to “in vitro” meat, a concept that combined many of my interests.

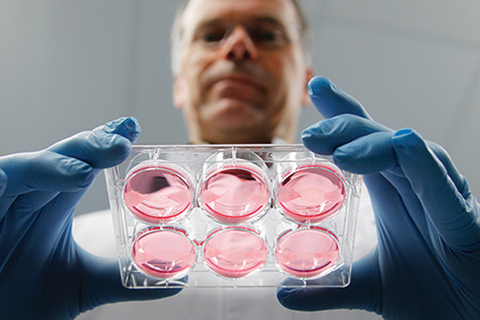

Today, I am the director of a non-profit organization in Toronto called New Harvest, which is developing alternatives to conventionally produced meat – including meat produced in a cell culture. In order to do this, scientists begin with an animal cell line, obtained through a simple biopsy from an animal of choice. Those cells multiply in a nutrient-rich liquid medium in a sterile environment, before being harvested and prepared much like animal-sourced meat. This summer, the first cultured-meat hamburger, a proof of concept using these techniques, will be produced and tasted in London. It will show the world that culturing meat is possible; however, more research is necessary to take this beyond the laboratory.

Because such alternatives can be produced under controlled conditions impossible to maintain on industrial farms, they can be safer, less polluting and more humane. A sterile environment would make a production facility far less prone to disease contamination than a factory farm. Producing meat through tissue culture would require 99 per cent less land and generate up to 96 per cent less greenhouse-gas emissions than industrial farming, according to a New Harvest–supported study in Environmental Science & Technology. And throughout the process, no animals would be slaughtered or exposed to ghastly conditions on factory farms, where most of our meat comes from.

If the concept is simple and the advantages are plenty, why is this new process not available today?

There is a lot of investigation left to do. For example, it is crucial that the liquid medium the meat cells grow in be completely plant-based. A major ingredient of cell media is animal serum, and we need to remove the reliance on animal products in order to be truly sustainable, humane and cost-effective. There are animal-free media out there, but they need to be optimized for the cells we are trying to grow. Practically speaking, we need to ensure that this can be done at a reasonable price point. We need to guarantee that this food is sustainable and meets safety standards. And we need to make sure meat lovers will be willing to make the switch, or at least try it.

All of this research requires funding – and this means telling the world why we need this technology. My graduate level education in biotechnology at U of T taught me how to bring science out of the lab and into society. I learned that the science that changes the world is half the science itself and half everything else – from the legal and political, to communications and research support. It was ultimately this work that prepared me for my role at New Harvest.

While steak grown in test tubes was referred to as “in vitro” meat when I was an undergrad, it is now known as “cultured” meat – which underscores that this is a new process, not a new product. It also harkens back to society’s early biotechnology experiments with beer, bread and yogurt.

“Cultured” may also prompt us to think that this meat is more civilized. I already believe it is.

Isha Datar graduated with a master of biotechnology from U of T in 2013. Learn more about cultured meat at new-harvest.org.

No Responses to “ Test Tube Burgers ”

From the University of Oxford's Atmospheric, Oceanic, and Planetary Physics department study published February 2019:

Researchers examined available data on the emissions associated with three current cattle farming methods and four possible meat culture methods.

Per tonne emitted, methane has a much larger warming impact than carbon dioxide. However, methane [from cattle] only remains in the atmosphere for a dozen years, whereas carbon dioxide [from the production of cultured meat] can persist and accumulate for millennia.

The scientists' climate model found that over the very long term, depending on production methods, the manufacture of lab meat can result in more global warming than the cattle farming. Cattle production required for very high levels of beef consumption does result in global warming, but it is not necessarily the case that cultured meat production would provide a more climatically sustainable alternative.