Turned Away for Smoking Weed? Not at This School

James Anderson welcomed students who used drugs to a new kind of school. For many, the effects were life-changing Read More

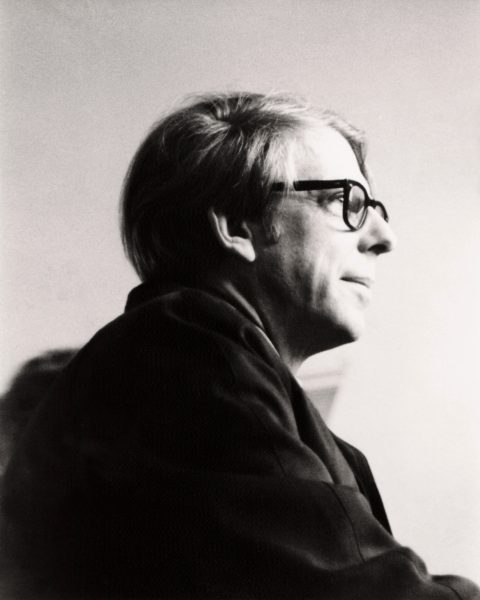

For all his success, James Anderson (MD 1953) must sometimes have viewed his press clippings with dismay.

A polymath to the nth degree, Anderson taught anatomy and anthropology at the University of Toronto in the late 1950s and early 1960s. He did research into the growth of children’s jaws and teeth that aided the development of orthodontics, and served as a consultant to a federal commission that, almost half a century ago, recommended the decriminalization of cannabis possession. He also helped launch the medical school at McMaster University in Hamilton, Ontario. Yet as late as 1975, when he was named Hamilton’s Citizen of the Year, he was still widely known in the media as the “Druggies’ Doc.”

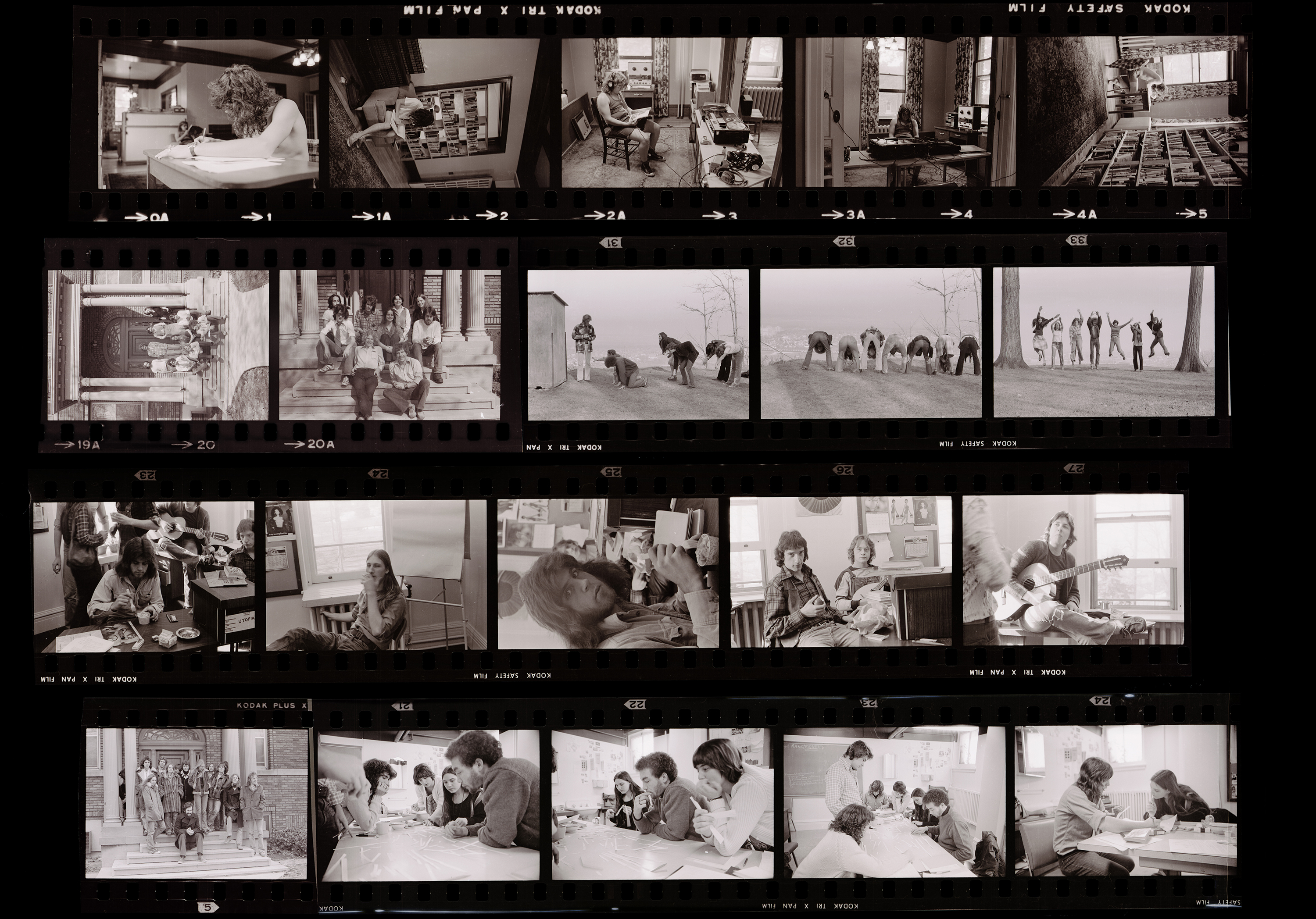

His sin was simple. At a time when the standard approach to substance abuse was punitive, Anderson – thinking drugs more symptom than cause – adopted what today we might call a harm-reduction approach. He met several young people with drug problems while conducting research into adolescent growth and development in the early 1960s and greeted them with a compassion that, for the time, was both radical and rare. He treated kids on bad trips, helped at a crisis centre that he’d established, advocated for young drug offenders in court and even established a school designed in part to give bright but disaffected teens an alternative to drug use. Called the Cool School, it opened in 1971 with just a handful of students, two staff members and a temporary home on the grounds of Chedoke Hospital in Hamilton.

Anderson was deeply irreverent, with a freewheeling style and a love of practical jokes. (A loyal Catholic, he once scared two priests with whom he’d attended a screening of The Exorcist by appearing afterwards dressed with his suit jacket on backwards.) On any given day, he used to say, he had used up his “seriousness quotient” by noon. After that, you couldn’t expect a straight answer from him.

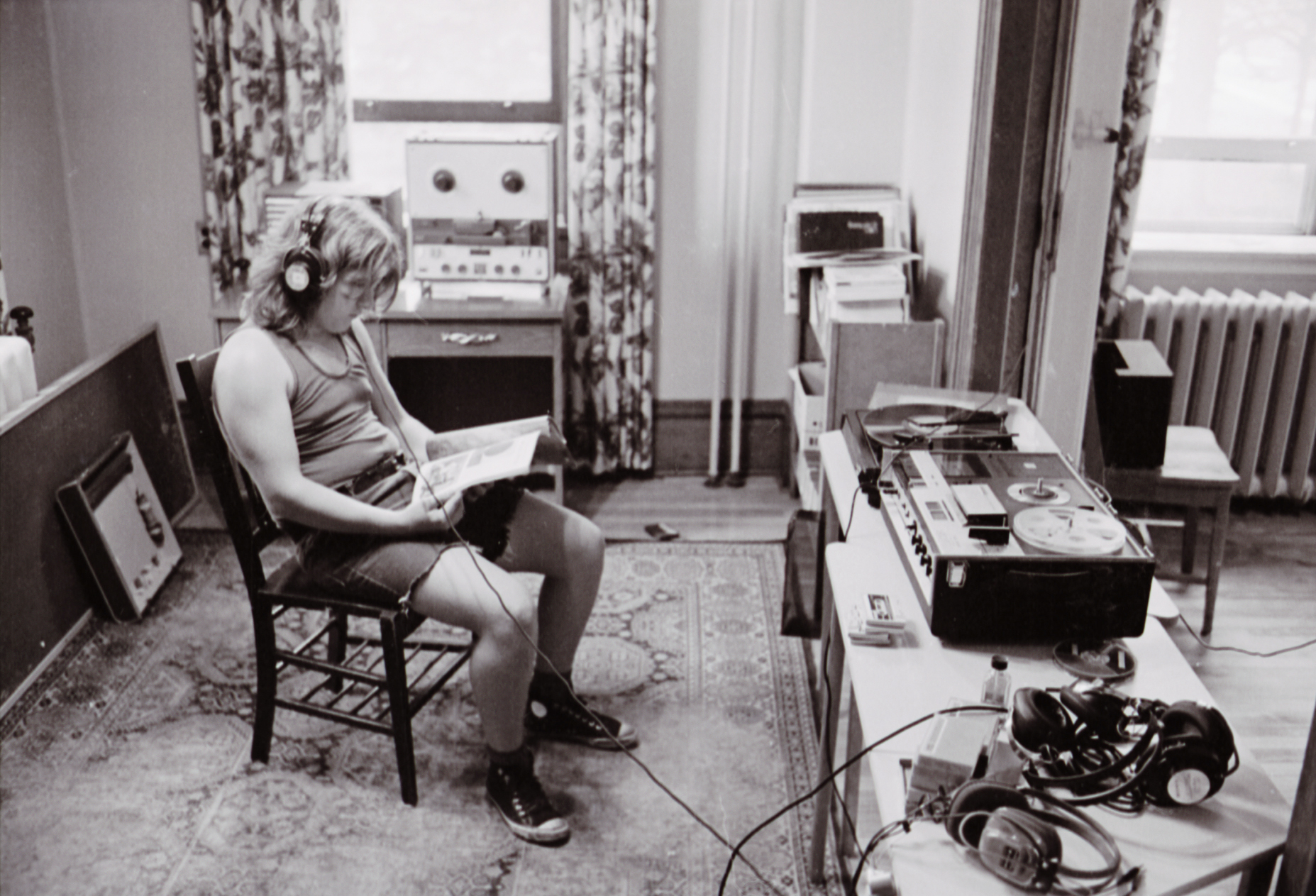

The school he founded mirrored that irreverence but also exhibited a deep commitment to a new kind of education that favoured learning over teaching and individual needs over institutional requirements. At Cool School, students had far more freedom – and responsibility – than they would have had at a regular high school. They participated in their own evaluation by keeping a regular log of their ambitions and accomplishments, and they were free to explore topics that interested them – within broad subject areas. So you might choose Mordecai Richler if the theme were Canadian literature. The idea, initially at least, was to create an intellectual project so interesting, alluring and potent that it could compete head-on with drugs.

Yet as feel-good as it might seem, the Cool School was no sixties-style paean to peace, love and happiness. Unlike the free schools of the era, which displayed a naive, almost innocent belief in a student’s ability to learn without any overt guidance, Anderson imposed a firm structure on the learning process. The best way to engage disaffected students, he thought, was to give them more control over their education. But at the same time he wanted to make sure they had the necessary skills for higher education, so staff set guidelines for subject areas and worked hard to improve students’ writing and interpersonal skills. Organized in small groups with a tutor, students learned to get along with others and accept criticism with good grace. It wasn’t exactly group therapy, but there was a lot of time to get to know each other.

The Cool School didn’t work for everyone but for those it did the effects were obvious and exhilarating

Over the 18 years of its existence, the Cool School evolved to accommodate students with any number of problems other than drugs, from undiagnosed learning difficulties to tense family relationships to severe mental health issues. But whatever the challenge at hand, Anderson and company always dealt with it by attempting to arouse a never entirely dormant love of learning. It didn’t work for everyone but for those it did the effects were obvious and exhilarating.

You’d notice the change in a student, says Ted Ridley, long-time co-ordinator at the school – a sudden attentiveness, an increased interest in feedback and the startling idea that learning might be fun. “There’d be kind of a rivalry in a group to see who could do the most innovative and engaging kind of presentation. They’d do role playing or a Socratic dialogue: ‘I’m a Roman centurion, interview me.’”

Maggie Fox noticed the intellectual glow during her brief time at the school in the late 1980s, in the last year of the school’s existence. Now the chief marketing officer for a major software firm, Fox was bored with regular high school and dropped out. The Cool School helped her re-engage. “It felt like we were getting away with something,” she says, “by being able to get a high school equivalency in that method.” Not that they were, adds Fox. “But it felt like, ‘Don’t tell anybody actually how interesting this is and how engaging it is’.”

For Trevor Stratton, who attended the school in the early 1980s, the program was a huge boost to his self-confidence. After years of failure in regular high school, due in part to a complicated family dynamic, his brief stint at Cool School made him realize he was a bright guy, capable of much more. “In Cool School,” says Stratton, “it just seemed to come clear to me that my personal life was so busy and chaotic it was distracting me from concentrating on the work itself. When I did focus on it, I excelled.” He’s now co-ordinator of the International Indigenous Working Group on HIV and AIDS.

Anderson believed in the value of life experience and the school arranged opportunities for the students to spend two weeks at a workplace that might test their newly acquired skills and enlarge their view of the world. Many of the students were deeply disillusioned with conventional society and Anderson thought some real-world evidence to the contrary might prove therapeutic. So a student with an antipathy to the justice system might visit a courtroom, and a student from one religion might hang out with the leaders of another. They’d observe, interview, maybe participate in the work, and then report back to their peers about what they had learned.

Always the emphasis was on personal responsibility, not just following your interests but getting the work done in a reasonable period of time. “We’d say the only important thing is time,” says Ridley. “You’ve got 168 hours in a week. You have to decide what you’re going to do with them.”

To students in the public system, the Cool School was “a place for druggies and flakes and losers,” says Ridley. But the Cool Schoolers themselves rather enjoyed their eccentric diversity. “It was sort of a funky, hippie crowd that ended up being there,” says Stratton, “some gender-variant people and the geek-chic. All of us were these misfits and when we got together in a group socially we had a lot of fun.”

The school had its hiccups. Ridley remembers one student who brought weed to school in an army ammunition pouch and another who tried to sell drugs to a teacher. “Oh, wrong customer,” said the pupil. Once, students partied in an empty schoolroom and chilled their beer with a portable fire extinguisher. Another school might have expelled the students. Not Cool School. If a student were doing something to jeopardize the existence of the school, such as dealing drugs too openly and thereby attracting the attention of the police, staff would intervene, but in the case of the chilled brew they merely brought up the problem at one of the school’s regular meetings.

To students in the public system, the Cool School was ‘a place for druggies and flakes and losers.’ But the Cool Schoolers themselves rather enjoyed their eccentric diversity

As outlandishly laid back as Cool School was, though, it wasn’t entirely unique. Progressive ideas in education were in the ascendant in the 1960s and by 1969 there were probably several hundred alternative schools across North America and dozens of books on the topic. Where the Cool School differed was in its coherent structure, its expectation of academic achievement and skill development and its underlying therapeutic focus.

In this it was a mirror of its founder, who had the rare ability to engage thoughtfully and sincerely with almost anyone. “It wasn’t just charisma,” says Ridley. He “got” the students and they responded in kind. Funny and even sometimes outrageous, he could defuse a situation with humour and quell a panic attack with “calm reassurance… Kids trusted him intuitively.”

Among educators, says Ridley, the reaction to the Cool School “ranged from genuine inquisitiveness, to bemusement or utter incomprehension, to the opinion that we were subverting legitimate education.” And yet the Ontario Secondary School Teachers’ Federation bestowed Anderson with the Lamp of Learning Award, which is given annually to recognize a non-member’s contribution to public education in Ontario. Anderson’s acceptance speech exhorted his colleagues to try harder, do better and put the Cool School out of business.

Shortly after Anderson’s death in 1995, former tutor Anne Snider wrote in a newspaper article that while many students at the school felt disillusioned and angry at the conventional school system, Anderson “was able to see through the anti-social behaviour to the Siddhartha within. He offered kids respect, self-direction and a world of exciting ideas… Few were untouched by the magical door he opened for them.”

No Responses to “ Turned Away for Smoking Weed? Not at This School ”

Good article -- and what a walk down memory lane! Cool School changed my life. The only thing missing from this article was more about the tutors. They weren't anything like mainstream teachers; it took a different breed of cat to work there. They were a unique group with a passion for learning who had a profound impact on the kids.

I was fortunate to have taught at an alternative school in Scarborough, Ontario, called ASE1, from 1989 to 2002. This article reminds me of why I loved it so much.

This article was a very true depiction of the experience I had at Cool School. I was in "D.A.'s" (Dr. Anderson's) class at Cool School in the early 1980s and it changed my view of myself and the world forever. Dr. Anderson was a great man and I thank God I met him.

I was a tutor at Cool School for over 10 years. I’d never before nor have since met a more complex, engaging, intelligent person than Jim. Working with him was a joy in my life that I hold dear in my memories.

I was lucky enough to have two chances to work with Jim Anderson and his staff -- once as a summer student in the original building in the late 1970s and then as a student teacher in the early 1980s in its last building. Dr Anderson, in addition to being one of McMaster Medical School's co-founders (among many other personal achievements) was a true innovator in inclusion and special-needs education. I was privileged to get to know him and see this remarkable place from the inside. I learned more there about how to teach than any Teacher's College. In many ways, current boards of education have taken on much of what they did. But there is still much more that could be learned from what "Cool School" was. I have to echo that the tutors -- Ted, Virginia, Bev -- and others who worked there were equally remarkable and special people, and I have to thank them for their kindness and inspiration! Thanks for the article! It is good to see that the school is receiving recognition for something that was truly unique and important.

I’m a Cool School graduate of 1976. It was a remarkable experience and played a significant role in my educational and life path. I went on to earn a BFA, MFA and MEd, and am now a professor. One of my favorite quotes of Dr. Anderson's to use when encouraging my students to complete their course work and strive for excellence was, “There are 24 hours a day and then there are the night times.”

One source for this magical thing called Cool School was Hermann Hesse's Magister Ludi, which Jim Anderson held in high esteem. Jim opened doors to a lot of things for all of us, but for me his stress on personal responsibility for one's own learning, and for the learning of others, had its roots in the imaginative and visionary world of that book. He could have had a very lucrative and rewarding career as an academic scientist, but instead poured his remarkable energy into this educational project that brought many young people out of confusion and darkness. Tutors Ted, Bev and Virginia -- and others I did not know -- were essential to this project and all infused with Anderson's spirit. May we never forget!

I was very fortunate to have had the opportunity to not only meet Dr. James Anderson ("DA") as a student, but to call him a close and dear friend.

I studied at Cool School in the early 1980s, and it was truly was one of the best times of my life. Jim understood that you cannot expect people -- especially teens -- to want to be better if you act superior.

He understood that learning is participation, not regurgitation. That failure and making mistakes should be encouraged rather than punished.

Jim realized (to the benefit of "the Coolies") that teens, or anyone seeking knowledge, can be encouraged to learn by exploring something they themselves are passionate about -- not just reading about how someone else did it, but actually doing it themselves.

Even today, in the middle of a historic global pandemic, teens of this generation are not taught that much differently than I was in public school. It's a shame that Jim’s legacy has disappeared.

My schoolmates of 1983-84 cheer and miss you, Dr. A.