How Will We Fix Fake News?

Technology gave rise to the current problems, but technology alone won’t solve them

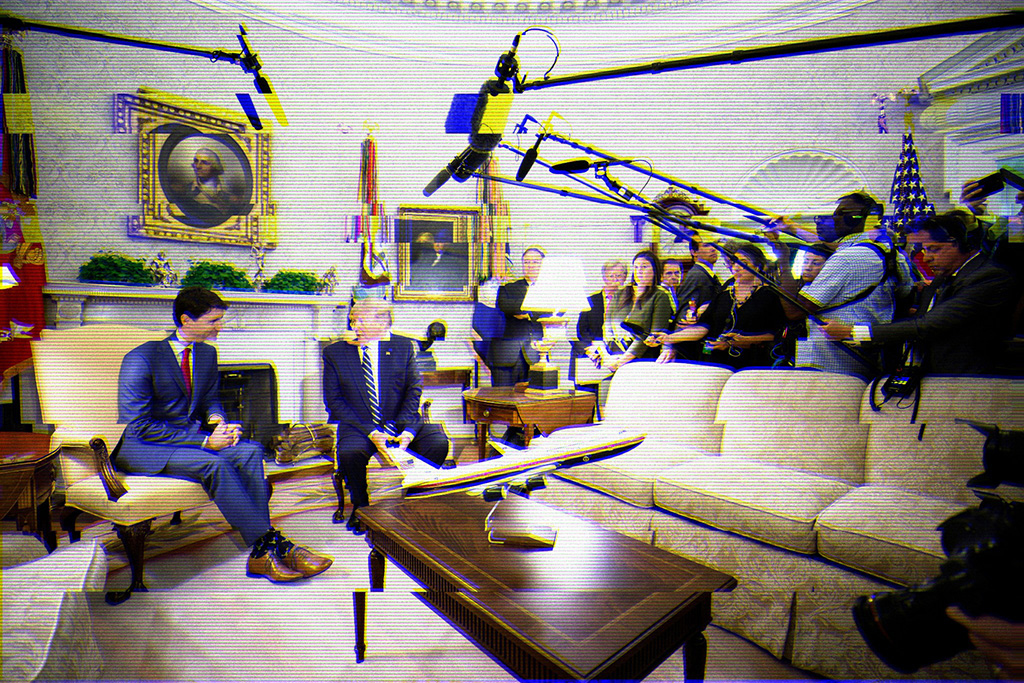

In the weeks leading up to the federal election, Canadian Facebook users saw some astonishing news pop up in their feeds: Prime Minister Justin Trudeau had paid millions of dollars to an accuser to hush up allegations of sexual misconduct. There was just one problem with the story: it wasn’t true. According to a joint investigation by Buzzfeed News and the Toronto Star, it was one of a number of dubious stories on Canadian politics that the Buffalo Chronicle, a U.S. website, paid Facebook to circulate.

It’s not clear how much impact the stories had on voters – after all, Trudeau won re-election, despite the very real blackface scandal. But the incident added to the sense of disorientation and distrust elicited by the modern information ecosystem. In a world of Twitter bots, deepfake videos and disinformation campaigns run by foreign governments, how do we know what’s real and what’s not? And how much does it matter?

“We used to have trusted gatekeepers,” says Jeffrey Dvorkin, the director of the journalism program at U of T Scarborough. “But the Internet has made the gate disappear. There’s no longer a gate, and there’s no longer a fence. It’s like we’re out on the bald prairie, without any kind of informational or intellectual support.”

Dvorkin is one of a number of researchers at U of T concerned with how we get information in the evolving online world. Taken together, their findings suggest that things are both better and worse than they might seem, and their work points the way to how we might be able to make sense of the complexities of understanding the world through the Internet.

Two recent scandals raised public awareness of the threats posed by new media. In the first, investigations by American intelligence agencies showed that networks of fake social media accounts linked to Russia conducted a co-ordinated effort to promote Donald Trump and vilify Hillary Clinton during the 2016 U.S. presidential campaign. In a separate scandal, a British private consulting company called Cambridge Analytica harvested personal information from Facebook users in order to target them with political ads.

75% of Internet users in two dozen countries say social media companies contribute to their distrust in the Internet.

Cybercriminals were the leading source of distrust, at 81%.

86% say they have fallen for fake news at least once.

Source: 2019 Cigi-Ipsos Global Survey on Internet Security and Trust

In response to concerns such as these, social media platforms have instituted some reforms. Facebook introduced an effort to crack down on false content by using third-party fact-checkers and by allowing users to flag potentially problematic posts. Twitter removed millions of “bot” accounts – automated accounts that can be used to amplify a particular message. It now also refuses all political advertising. And in the wake of COVID-19 misinformation, social media platforms have announced that they are co-operating with each other to weed out falsehoods and actively promote authoritative sources.

In Canada, with its relatively short election cycles and less polarized electorate, the issue with election interference, at least, seems less urgent than in the United States. The Public Policy Forum in Ottawa and the Max Bell School of Public Policy at McGill University in Montreal started the Digital Democracy Project in 2018 to study the media ecosystem just before and during the most recent Canadian federal election. Peter Loewen, a University of Toronto professor of political science, is in charge of survey analysis for the project. He says the best news is that there was very little disinformation – that is, intentionally fake news – circulating during the election. The Buffalo Chronicle stories were concerning but not typical.

“If you look at the totality of false things that would appear in credible news outlets, the vast majority of them are coming from political parties, and not from anybody else,” Loewen says. “But that doesn’t mean that people aren’t misinformed. The argument we make is that there is, in fact, a fair amount of misinformation in Canadian politics…. But a lot of misinformation is attributable just to what people are reading in normal news.”

Rather than retreating into partisan “echo chambers,” where they only hear information that confirms their views, the majority of Canadians consume news from the same traditional news sources. “Basically, everybody in Canada is consuming some of their news from the CBC, and from the big national broadcasters and the big national papers,” says Loewen. “It’s not that we’re in silos.”

Oddly, and unfortunately, people who consumed the most news during the election, regardless of the source, were also the most misinformed when asked factual questions such as the size of the federal deficit or whether Canada was on track to lower carbon dioxide emissions.

It seems paradoxical. But Loewen points out that even an accurate story from a mainstream news source rarely consists only of verifiable facts. It will also necessarily report the views and assertions of a number of sources, such as politicians and political parties, who may provide misleading or false information. Combine this with the tendency of people to seek out and remember information that confirms their views, and it explains why taking in more information might actually lead to being more misinformed.

And although everyone might be consuming news from the same sources, the facts and stories they tend to share with other users aren’t the same. The most partisan social media users were much more likely to share stories from the mainstream media that were in line with their own political beliefs.

Finally, although Canadians are not becoming more extreme in their beliefs, they are becoming more “affectively polarized.” In other words, they are more likely to see people with different political beliefs in a negative emotional light. “We have problems, but our democracy is working pretty well,” Loewen says.

For Alexei Abrahams, the picture is more problematic. Abrahams is a post-doctoral researcher at the Citizen Lab at the Munk School of Global Affairs and Public Policy. He is especially interested in social media in the Middle East and North Africa. There, governments have responded to the openness of social media by finding ways to use it to manipulate and misinform their own citizens and those of other countries. “It’s a case of data poisoning,” Abrahams says. “You don’t know what to believe.”

Social media gained importance in the region during the so-called “Arab Spring,” a string of popular protests between 2010 and 2013 that were organized in part through Twitter and Facebook. Social media is an especially important outlet for public expression in the region because most of the countries are authoritarian, leaving few other outlets for civic engagement, Abrahams says.

But since the Arab Spring, governments in the region have made increasing efforts to manipulate social media. One example is through the use of hashtags on Twitter, such as #Tahrir_Square or #Iraq_Rises_Up, which are used to label and organize content. They provide a way to engage in a conversation, and also give an indication of what issues are important to people and where they stand on them. However, they are also vulnerable to manipulation.

For instance, in the ongoing diplomatic crisis between Qatar and Saudi Arabia, one Saudi demand was that Qatar shut down the Al-Jazeera news agency. On Twitter, a hashtag translating as “We demand the closing of the channel of pigs” quickly trended. But researchers discovered that 70 per cent of the Twitter accounts using the hashtag were part of a co-ordinated network – either automated bots or human-operated accounts that had been set up primarily to promote that hashtag.

Likewise, #Get_out_Tamim! trended in Qatar, apparently aimed at Qatar’s ruler, Tamim bin Hamad Al Thani. But closer examination showed that it was being promoted by a network that included Saudi influencers and Saudi-controlled bots. In other instances, popular hashtags are flooded with nonsense tweets, making them unusable.

Efforts like these have made it difficult to tell what people in the region are really thinking. Even worse, these efforts make it hard for people living in the region to trust what they read on social media – and discourage them from using social platforms to get politically involved, since it’s never clear what’s real and what isn’t. Although social media started as a “liberation technology” in the region, it is increasingly used as a tool of repression, Abrahams says. “Now it’s a means by which authoritarianism will reassert itself. It’s a means by which human beings will be dominated, rather than liberated.”

Abrahams says it’s difficult to come up with technical fixes for social media’s vulnerability to manipulation. “Algorithmically, how are you going to stop political influence? How do you distinguish malign influence from a user expressing an opinion?” he asks. One fix that could work is for social media platforms to spread the influence around. Twitter and other sites tend to be dominated by relatively few users who get the majority of shares, likes and retweets. Sometimes this is because of their positions as politicians or celebrities. But it’s often simply a network effect. A user gets a small initial advantage for some reason, more people follow him or her, and the increased popularity leads to even more popularity in a case of “the rich get richer.”

Facebook CEO Mark Zuckerberg says the company employs 35,000 people to “review online content and implement security measures.”

He says Facebook also suspends more than one million fake accounts every day, usually “within minutes of signing up.”

For authoritarian regimes trying to influence social media, these influencers can become targets – people who can be persuaded or intimidated into following the government line. Social platforms could instead help level the playing field algorithmically, making sure that tweets from lower-profile users are more likely to be seen, so that conversations aren’t automatically dominated by already influential users.

For his part, Dvorkin says that we need to work out new ways to help users cope with the transformed information landscape. “I don’t want to imply that we should go back to the way it was before 1990. Because we can’t uninvent the technology. But we have to develop some mechanisms – whether they are legal or cultural or whether it’s civic-mindedness – that allow us to reject certain forms of information because they are damaging to our culture. How do we manage that? How do we help the public do some information triage?” Dvorkin thinks there is probably a role for government, in partnership with legitimate media organizations, to play a role in vetting information.

And what of social media companies themselves? They have argued that they are not ultimately responsible for the speech that happens on their platforms. But Vincent Wong, the William C. Graham Research Associate at U of T’s International Human Rights Program in the Faculty of Law, says there is a growing consensus that social media platforms should be held accountable for misinformation on their platforms – even if how to do so isn’t clear. The platforms have so many users, and carry so many messages, that the logistics of monitoring everything is daunting. Combine that with worries about how to judge what content should be allowed and what content should be censored, and it is a difficult problem that will take time to work out, he says.

In the meantime, Prof. Peter Loewen thinks we should all take a moment of pause before we click “share” on a story that may confirm our political views but is of questionable credibility. “I think, generally, that people should try to be less and not more political,” he says.

Covid-19 Pandemic Sparks Its Own Fake News Stories

As a novel coronavirus began to make its way around the world earlier this year, disinformation campaigns were not far behind. Just as North Americans were being told to stay at home to prevent its spread, the European Union was warning of a co-ordinated disinformation campaign by official Russian sources designed to spread fear and confusion. Chief among the false claims: COVID-19 was the result of a biological warfare agent manufactured by Western countries.

The campaign added to and amplified misinformation swirling around the world as people tried to make sense of the new threat. In March, the Guardian and other news outlets quoted from a leaked report by a European Union team that monitors disinformation campaigns. “Pro-Kremlin media outlets have been prominent in spreading disinformation about the coronavirus, with the aim to aggravate the health crisis in western countries by undermining public trust in national healthcare systems,” the Guardian quotes the report as saying.

Kerry Bowman, who teaches bioethics and global health at U of T, fears people may be more likely to believe false claims at a time of crisis, adding to their sense of alarm. “Because they’re already anxious they’re more likely to jump on the misinformation,” he says. “The fundamental public health principle we need to stick to right now is that we have to have the trust of the public. Information has to be clear and accurate.”

No Responses to “ How Will We Fix Fake News? ”

Greg Keilty (BA 1970 St. Michael's) writes:

This is a fresh, clear discussion of an increasingly important issue. I would support the view that social media platforms must be held accountable for misinformation that they publish. But that adds a cost of doing business (one they could easily bear) so they will continue to resist it. Serious pressure from government will be required. Government regulation and enforcement have been out of fashion for a generation, with quite negative consequences in many areas -- most notably now in long-term care homes.

Regulation isn't a punishment. it's a necessary aspect of having a healthy society and healthy businesses. We've just had this pointed out at a terrible cost with long-term care homes. Ontario, where I live, has a Ministry of Health and Long-Term Care. I believe there are specific laws requiring that a certain standard of care be met. I assume the corporations who dominate this business have also successfully resisted any serious enforcement. The best we can say is that the Ministry of Health and Long-Term Care didn't care enough to play their, admittedly difficult, role. As a result, the price -- paid by others -- has been very high.

The lesson for social media regulation is to get on with it in a serious fashion before there are more serious consequences.