Writer Jenny Hall asked U of T Mississauga sociology professor Kelly Hannah-Moffat about the controversial practice of putting prisoners into solitary confinement, now under review in Ontario. Hannah-Moffat is the director of the Centre of Criminology and Sociolegal Studies at UTM.

What does solitary confinement mean in practice?

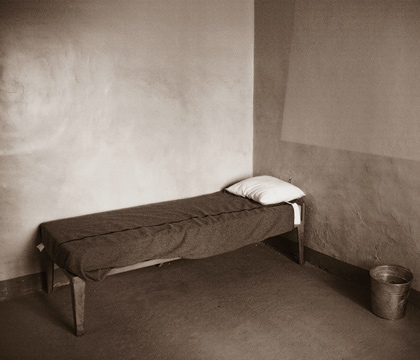

Normally, you are in a cell alone for 23 hours a day. You are allowed out for an hour for a shower or for recreation. You can walk around, but you’re by yourself. Normally, the movement to the recreation space is in shackles and handcuffs. Many cells are subject to 24-hour monitoring by camera. A prisoner in solitary confinement can also be denied access to visits, programs and services, and certain treatments.

When is it used?

A disciplinary segregation can occur when an offender violates an institutional rule. More commonly, prisoners are placed in segregation when they might injure themselves or are difficult to manage. This might be somebody who causes fights or is prone to victimization. It might be someone suffering with acute mental health issues or who is at risk for committing suicide.

How common is solitary confinement?

Correctional Service Canada will say that it does not use solitary confinement but instead uses “administrative segregation” or a “secure unit.” This is a bit of linguistic gymnastics because each is a secured space where there is minimal freedom and high surveillance. So we don’t have clear numbers. But we do know from reports from the Office of the Correctional Investigator that there were 8,328 admissions into segregation in 2013–14. This is up from 7,137 in 2003–04. The statistics do not indicate how long prisoners stay in segregation.

How do prisoners in segregation compare to those often seen in films and on TV?

We tend to see prisoners as terrifying, violent predators. But that’s not representative. Many have mental health problems or cognitive impairments and are struggling with complex and interconnected issues: addiction, abuse and trauma.

Is it legal to place people with mental health issues in solitary confinement?

The UN says that you should not. We don’t have the proper resources to address mental health needs in custody. People in custody don’t have good access to psychologists or to staff with appropriate levels of training to deal with people who are ill. The Office of the Correctional Investigator and many international and local advocates have raised concerns about segregation and its damaging and sometimes lethal effects. Yet it continues.

Does solitary confinement work when it’s applied for disciplinary reasons?

You might think that if we put somebody in segregation, they’re going to learn their lesson, behave properly and follow the rules. There’s no empirical evidence to support this. In fact, research shows that segregation can actually exacerbate the negative behaviour you are trying to control. It can create irreversible psychological damage.

Could that same logic mean that prison in general isn’t effective?

There is no evidence that says prison is effective in reducing crime. It isolates people’s mobility for a period of time, but it does very little to ensure that someone won’t reoffend in the future.

Yet being tough on crime is a popular political stance.

The desire for retribution is understandable, but it doesn’t make good policy. The question is: how would you like a person who has been in prison to be returned to society? Would you like them to come back angrier and more damaged? Or would you like them to come back with a renewed sense of purpose and with the opportunity to take their life in a different direction?

Recent Posts

U of T’s Feminist Sports Club Is Here to Bend the Rules

The group invites non-athletes to try their hand at games like dodgeball and basketball in a fun – and distinctly supportive – atmosphere

From Mental Health Studies to Michelin Guide

U of T Scarborough alum Ambica Jain’s unexpected path to restaurant success

A Blueprint for Global Prosperity

Researchers across U of T are banding together to help the United Nations meet its 17 sustainable development goals

4 Responses to “ Locked Away ”

Sociology professor Kelly Hannah-Moffat mentions that solitary confinement may cause irreversible psychological damage. Given the known impact of solitary confinement on prison inmates, it is shocking to know that many public schools in Ontario now have established similar practices. Many schools have small rooms which are called "time out rooms" or "calming rooms." Students are isolated in these rooms for a variety of reasons with no tracking of how long or how often they are used. As a faculty of education student at OISE, I was not even aware that this practice existed in public schools in Ontario. It would be interesting to see a similar interview from an education perspective.

Louise Murphy

MEd 2001

Georgetown, Ontario

Louise Murphy's comment could lead to misconceptions about the "sensory" rooms used in Ontario's public schools. I work with special needs students in many schools and classrooms in Mississauga. These sensory rooms are attached only to special education classrooms. They are primarily used with children with autism, many of whom are hypersensitive to noise, and get overwhelmed by normal classroom noise. They are never locked in this room. In most cases the room is left open.

Sometimes, these rooms contain coloured lights and dimmers. They have mats on the floor, bean bag chairs, fitness balls, and are used by children with severe developmental delay and perhaps physical disabilities. It is a chance to get out of their wheelchairs and crawl around. They are stimulated by the lights. Staff are usually in there with them. Medically fragile children who may use the room for a nap.

There are also violent children who can hurt themselves, other children and staff -- and occasionally, when they are losing control, they are asked if they would like to go into the sensory room to calm down. Never are they locked in that room. They are free to come out at any time.

Dawn Ellis

Mississauga, Ontario

Louise Murphy likens the "time-out" and calming rooms available for student use in Ontario to the solitary confinement found in prisons. There is little that is inherently similar about these spaces. Solitary confinement is a punishment. The prisoner has no control over when the confinement will end. The spaces that have been set aside in schools for students to choose as a haven to limit external stimulation should not be equated with solitary confinement.

Carol Nash

BA 1980, BEd 1981, MA 1984, PhD 1989

Toronto

The two comments supporting the use of seclusion in schools are very troubling. These comments contain many inaccuracies and may lead the reader to believe that the seclusion of children is acceptable. Accurate information about the use of seclusion rooms in schools may be found in the following report: http://www.inclusionbc.org/sites/default/files/StopHurtingKids-Report.pdf .

Although this report focuses on schools in B.C., the same concerns exist in Ontario schools.