Four ideas out of 23 for building an even better Toronto

Preserve Toronto’s trees long into the future.

Toronto’s trees aren’t just beautiful – they clean the air, cool the city, provide a habitat for urban wildlife and even intercept rainfall to reduce strain on the city’s sewer system. But a healthy urban canopy doesn’t happen on its own – someone needs to plant new trees, save existing ones and protect against pests and disease. It’s a lot of work for overwhelmed and budget-constrained municipal departments – and that’s where Sandy Smith’s students step in.

Smith, a professor of forestry, links students in the Master of Forest Conservation program with community groups across Toronto to keep their neighbourhood green. Each student team creates an urban forest management plan, which includes: community objectives, an inventory of existing tree cover in the neighbourhood, a resource of key websites and references, and one- five- and 20-year plans. The community then has an urban greening strategy to move forward with the city.

David Grant, who works with Cabbagetown ReLEAF, a community group that participated in fall 2014, says the idea is a winner. “Our plan is already in action,” he says. “When you have a bunch of great people getting together to share knowledge, it’s totally empowering. Three of the students have stayed on with Cabbagetown ReLEAF and we continue to evolve and grow.”

That students often remain with the community group is an indicator of the program’s success, says Smith. For both students and communities, she adds, the course “is giving knowledge and knowledge is power. That’s what universities do.”

Improve both indoor air quality and energy efficiency at Toronto Community Housing.

“The average Canadian spends about 90 per cent of their time inside buildings,” says Jeff Siegel, a civil engineering professor. “But over the past few decades of improving energy efficiency in buildings, a lot of the things we’ve been doing have actually been making indoor air quality much worse.” Since the air we breathe can affect health in many ways, with air particles linked to heart disease, stroke and cancer, Siegel is understandably interested in doing something about Toronto’s indoor air.

So, as the Toronto Atmospheric Fund and Toronto Community Housing work on energy retrofits for seven high-rise buildings, Siegel is researching exactly what the indoor air quality is like in these apartments. His findings will inform the actual repairs to be made in 2016.

The research team loaded up 75 units across the buildings with different equipment. In some, a six-inch box on the wall measures carbon dioxide, temperature and relative humidity every 15 minutes. Others will enable Siegel to do chemical analyses on dust. They also have instruments in place to track formaldehyde, radon and ozone levels. All this data will be measured both pre- and post-retrofit. “We shouldn’t see energy efficiency and indoor air quality as opposed to each other,” says Siegel.

Measure vehicle emissions across the city and help Torontonians reduce their exposure to pollutants.

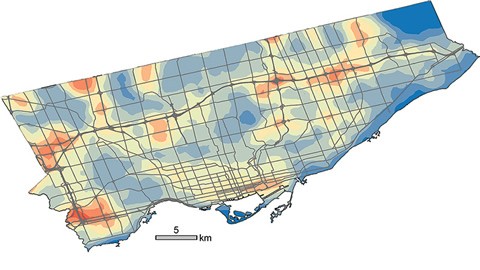

The map below shows hotspots of vehicle pollution across Toronto – data that Greg Evans, a chemical engineering professor, collected in partnership with Environment Canada. Students and scientists walked the city, making measurements on hand-held devices that were extrapolated to create the map.

Compared with blue areas, the orange spots have up to four times the concentrations of ultrafine particles, a good indicator of vehicle pollution. Traffic-related air pollution, which has been linked to asthma, heart disease and cancer, may affect half of homes in Toronto – even those off major roads in the city’s famous leafy neighbourhoods. “We’re starting to understand that we need to measure on a more micro scale, especially around major roadways and within urban centres,” says Evans.

Design new roads and retrofit old ones to support biodiversity and wildlife habitats.

From an animal’s-eye view, Toronto is a patchwork of green spaces linked by river valleys, and separated by terrifyingly dangerous roads. Since most species have a natural range of movement that’s much larger than your average park or ravine, ensuring animal mobility across the city isn’t just about preventing roadkill, says Prof. Namrata Shrestha. Species penned in a small area can’t find enough food or mates and die out, she says, which has spin-on effects to the ecological health of all the urban green space.

Shrestha, a prof at the School of the Environment, is a landscape ecologist – she studies how to reduce the impact of infrastructure networks on wildlife. Her team counts road kills and logs their locations. They post cameras at bridges and culverts to track which animals slip across under the road and when. By combining the data, Shrestha gets a detailed picture of not only which species are at risk but how – which lets her make specific recommendations.

“I work with the Toronto and Region Conservation Authority as well as with the Toronto, Peel, York and Durham regions,” she says. If new roads are in the pipeline or existing roads are due for a major repair, she can recommend the most helpful types of bridges and culverts, including suggestions on how tweaks to the design of a culvert could make it more attractive to animals.

Shrestha thinks in terms of the entire network, rather than trying to save individual habitats, but actions often focus on certain areas of the city. “If the city spends money strategically, in some specific locations, we can be successful in preserving and enhancing wildlife habitat and biodiversity throughout the region.

See how U of T students, faculty and researchers are helping to make Toronto a more:

Recent Posts

People Worry That AI Will Replace Workers. But It Could Make Some More Productive

These scholars say artificial intelligence could help reduce income inequality

A Sentinel for Global Health

AI is promising a better – and faster – way to monitor the world for emerging medical threats

The Age of Deception

AI is generating a disinformation arms race. The window to stop it may be closing