An old woman sits in front of her dinner. Her mind has wandered, and she hasn’t taken a bite for a few minutes. Brian notices. “Do you not like your pasta?” he asks solicitously. “Please pick up the fork in front of you and put some pasta on the fork.” She does, and Brian smiles encouragingly.

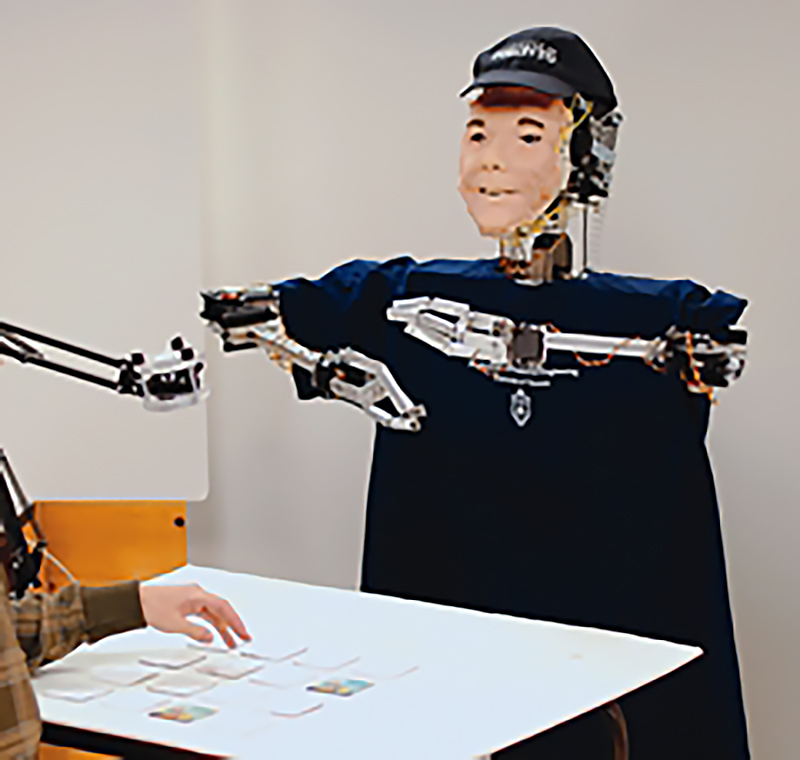

What’s odd about this scenario is that Brian’s voice is computer synthesized, and his face is made of silicone rubber. The smile is controlled by wires and actuators built into his head.

Brian is a human-like robot being developed by a research team led by Goldie Nejat, a professor of mechanical and industrial engineering. Nejat hopes that Brian soon will be helping the elderly in assisted-living facilities and eventually even in their own homes. This fall she hopes to test him at a long-term care facility at Baycrest in Toronto.

“The idea is that Brian will be a socially assistive robot for the elderly with cognitive impairment,” says Nejat, who is also the director of the Autonomous Systems and Biomechatronics Laboratory at U of T. As baby boomers age and there are fewer people in the workforce to take care of them, robots such as Brian could aid health-care staff, she says.

Until now, robots have mostly been used for what roboticists call the “three Ds” – jobs that are dirty, dangerous and dull. But advances in computer vision, speech recognition and artificial intelligence, among other things, will soon bring us social robots that can interact in a natural way with humans.

Brian looks part C-3PO, part department-store dummy. His torso is mounted on a platform, and his arms are clearly mechanical. The artificial look is intentional, Nejat says. Robots that look too human can be confusing to the elderly, and even creepy.

Despite all that, Brian does manage to create a human-like presence. When he speaks you look at his face, not at the laptop that for the moment serves as his brain. That sense of presence is one reason to use a robot, and not simply a computer animation on a screen, Nejat says.

In addition to helping people remember to eat, Brian can also help people play a card-matching memory game, giving encouragement and hints to the human player.

Eventually Brian will be able to roll around a room, looking for people to interact with. He might even be an in-home assistant, chatting, keeping track of medication, and generally engaging with and helping the person he lives with.

Nejat says that the biggest challenge is teaching Brian to recognize people’s behaviours. By monitoring things such as word use, body language and gestures, gaze and even heart rate, Brian will be able to tell if someone is upset, engaged, happy or sad, and change his own behaviour accordingly. If he recognizes a person is sad, for instance, he might try especially hard to cheer them up. “These robots will help to improve our quality of life,” she says.