After spending the first portion of his career in banking in Latin America, Stephan Krajcer came to a stark conclusion about the future of his industry. “Financial instruments,” he says, “should be born digital.”

Krajcer is the founder of Cuore Platform, which last year joined the Creative Destruction Lab, the accelerator program at U of T’s Rotman School of Management. Krajcer’s vision is to develop “smart contract” technology that will allow traditional banking transactions, such as mortgages, which typically require signatures on printed copies, to be completed entirely without paper. As Krajcer explains, his eight-person team is deconstructing the steps and figuring out how to digitize each one of them, especially for routine and universal transactions such as promissory notes.

Cuore’s nascent service is part of a poorly understood but potentially game-changing technology known as “blockchain.” Developed a decade ago to facilitate the trading of cryptocurrencies such as Bitcoin, blockchain’s premise is that much of the delay and cost can be edited out of financial transactions by recording them on “distributed ledgers.” These ledgers are a bit like shared spreadsheets on a Google drive, except that they record transactions in a way that is transparent, secure, constantly updated and unalterable. Encryption ensures that entries are tamper-proof.

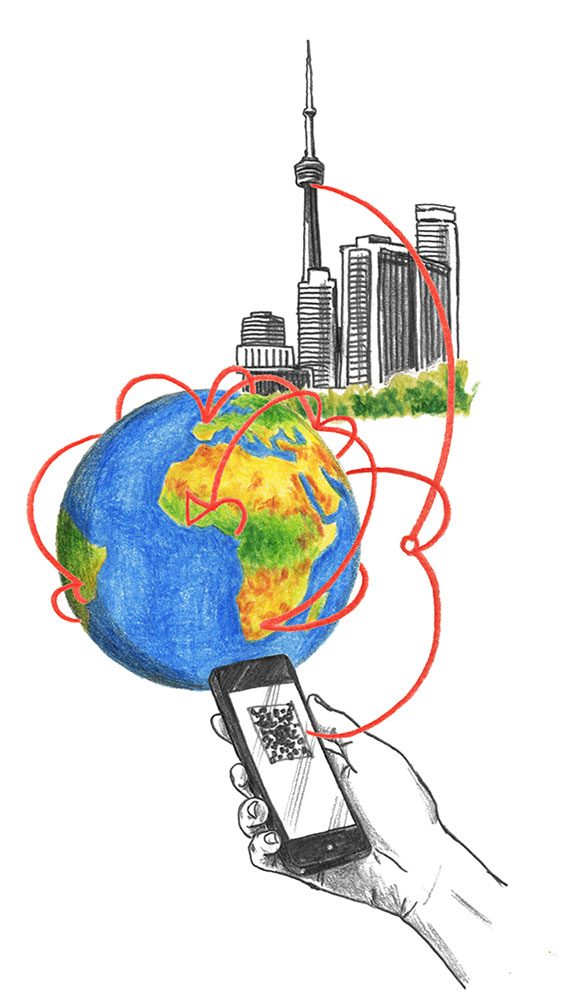

Andreas Park, a finance professor at U of T Mississauga, says blockchain allows for people to exchange assets directly, without a bank or other broker. Take the case of a typical wire transfer to a relative in another country – a transaction that costs up to 10 per cent of the initial amount and may involve a delay of days. With blockchain, such transactions could become practically instantaneous, completely verifiable at both ends and far less expensive. As Park observes, blockchain raises difficult but important questions about the value of the institutional go-between.

Park believes blockchain also holds out an important opportunity for research and education – and the sort of disruptive entrepreneurial activity Cuore and hundreds of other startups are undertaking. To advance students’ understanding of the technology, U of T has launched workshops on blockchain through Rotman’s Financial Innovation Hub in Advanced Analytics, established last year with $1 million from TD Bank Group and seed funding from the Rotman Catalyst Fund. The Catalyst Fund was created in 2016 by a $30-million bequest from donor Joseph Rotman’s estate.

U of T has also created an interdisciplinary research project, UTLedgerHub, which Park oversees with Andreas Veneris, a computer and electrical engineering professor, and Fan Long, a professor of computer science. UTLedgerHub is examining potential applications of blockchain in finance and economics. The goal of these efforts, says Park, is to enable U of T both to teach blockchain to students and to innovate with the technology through collaborations with industry.

When Park began offering a course on blockchain to UTM undergraduates in 2017, the student response was immediate. “You could feel the excitement in the room,” he says. Many were familiar with blockchain because of the hype around Bitcoin. Each time Park taught the course, he asked for a show of hands to see how many had bought this digital currency. Early on, none had. But by last year, when extensive trading in Bitcoin had caused its price to soar, about a third owned some form of cryptocurrency. “They had a better understanding of what I’m talking about.”

The students who have flocked to Park’s classes are also aware of the fast-growing career opportunities to develop and sell software related to this technology. Veneris says Toronto, already a research and business hub for artificial intelligence and financial technology, is also considered a global centre for blockchain development. Park adds that it’s good for local employers to be able to hire young people with these emerging skills. “There’s a huge opportunity at the moment.”

(Source: Forbes, February 2018)

1—New York, 2—San Francisco, 3—London, 4—Singapore, 5—Boston,

6—Chicago, 7—Toronto, 8—Palo Alto, 9—Austin, 10—Sydney

Illustration by David Sparshott

One of the challenges for researchers and entrepreneurs alike is in developing practical uses for the technology. They must essentially reinvent the long-established and complicated practices that have grown up around financial transactions such as mortgages and stock trades. Despite the fact that we can do our banking on smartphones, the back end of these activities remains paper-bound and heavily regulated. No one, Park says, would build a bank from scratch and make it such a slow-moving bureaucracy. Yet allowing transactions to be executed automatically and recorded on a blockchain is a complicated process.

One of the difficulties involves translating necessary regulation such as anti-money-laundering rules or know-your-client practices into computer code. While some blockchain enthusiasts espouse a kind of computer anarchism, Veneris says the technology will “need to be regulated to some extent.” A few countries, such as China and Vietnam, have introduced regulations for the use of blockchain, to avoid a loss of control for their centralized regimes. Others, like the Irish government, have gone in the other direction, sponsoring blockchain hackathons. “Nobody,” Veneris observes, “has a clear direction of where this is going.”

Beyond all the blockchain hype and jargon, and the endless complexities of the banking world, the basic idea behind this emergent technology is almost philosophical in nature. Veneris sums it up in the form of a question: “How do you trust?” This question resides at the core of both blockchain technology and a global financial network that has developed byzantine ways to ensure that all parties in a deal get what they bargained for (and which has room for improvement, notes Park).

Blockchain’s promise is that trust is literally programmed into a new generation of financial systems. As Veneris says, “We’re one step closer to having machines do the trust for us.”

Recent Posts

People Worry That AI Will Replace Workers. But It Could Make Some More Productive

These scholars say artificial intelligence could help reduce income inequality

A Sentinel for Global Health

AI is promising a better – and faster – way to monitor the world for emerging medical threats

The Age of Deception

AI is generating a disinformation arms race. The window to stop it may be closing

2 Responses to “ In Machines We Trust ”

This is an excellent and thought-provoking article.

Blockchain alters the nature of a financial transaction as we know it. It is a different way of transacting money that could result in more money laundering and fraud across borders. International standards enforced by an international body that verified the source of funds and reported breaches and to law enforcement agencies might enhance trust. In my opinion, this is an area that needs formal input -- not just from researchers, educators and traders, but also from legal practitioners, bankers, academics and technology experts.