The noisy rat-a-tat produced by this First World War rattle (on display in the Memorial Room at Soldiers’ Tower) warned all those within earshot of an impending poison gas attack. In the trenches the only criteria for alarm devices were that they be loud and distinctive – but as a bonus, rattles didn’t require use of the lungs. Soldiers used wooden rattles, klaxon horns and steel triangles, but also made alarms from whatever materials they had available, such as empty shell cases and church bells.

Poison gas caused more than a million casualties in the First World War. Widespread use of lethal gas began in April of 1915 during the Second Battle of Ypres in western Belgium. This battle, known as the Canadian Army’s “Baptism of Fire,” gave Canada’s soldiers a reputation as a force to be reckoned with. Yet, in 48 hours of fighting, 6,035 Canadians – one in every three soldiers in the First Division – were injured or killed. More than 2,000 died. The University of Toronto suffered many casualties at Ypres, including medical student Norman Bethune (BSc Med 1916) who was wounded in the fighting and spent three months recovering in a British military hospital. Prof. Harold Innis was another member of the U of T community who was gassed during his service overseas. Pictured on our cover in 1917 wearing a gas mask around his neck, a “very tired” Innis had just come off duty as a signaller with the Fourth Battery of the Canadian Expeditionary Force in Western Europe.

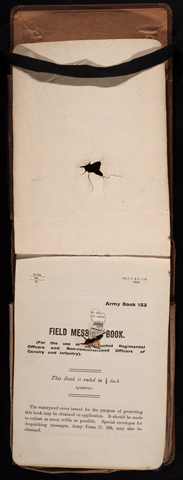

with shrapnel damage

On April 9, 1917 at Vimy Ridge, gas shells hit between his feet but “did no damage other than to release a rather stifling chlorene (sic) gas.” A few months later Innis was not so lucky when shrapnel from a German shell ripped through his right thigh. The wound was severe but not lethal, thanks in large measure to his avowed “habit of carrying around great quantities of stuff in my rucksack.” Books and other equipment stopped additional shell fragments from entering his body. The pictured Field Message Book, which now belongs to the Harold Innis collection at U of T Archives, was among the objects that may have saved his life.

Recent Posts

U of T’s Feminist Sports Club Is Here to Bend the Rules

The group invites non-athletes to try their hand at games like dodgeball and basketball in a fun – and distinctly supportive – atmosphere

From Mental Health Studies to Michelin Guide

U of T Scarborough alum Ambica Jain’s unexpected path to restaurant success

A Blueprint for Global Prosperity

Researchers across U of T are banding together to help the United Nations meet its 17 sustainable development goals

2 Responses to “ Objects of Salvation ”

Question for Alice Taylor: Reference is made to FitzGerald’s backyard stable at 145 Barton Ave. I was born at 289 Barton Ave., which is on the south side of Barton. In Toronto odd-numbered buildings are on the south side of the street.

There was, just east of my boyhood home, the foundation of the stable where tetanus was first made but that was on the north side of Barton. If you Google “145 Barton Ave” it comes up on the north side of Barton. The south side is taken up by Christie Pitts,from Crawford east to Christie Street.

Is Google wrong, am I wrong, is the address wrong? Any thoughts or comments?

Great article in a great publication.

Reply: Thank you for the comment and kind words! Google seems to be mixed up – all the odd numbers are indeed on the south side of the street, including 145, located just east of Christie Pitts.

I am a retired Anglican priest who continues to "fill in" at a small rural parish in Alberta. My father's eldest brother was killed in June 1918 and his body was buried in the British Military Cemetery in Boulogne, France. My wife and I visited this beautiful cemetery some years ago, following a routine of my paternal grandparents who travelled to Boulogne each year until their deaths in the mid-1930s.

This year, on November 9 at the Remembrance Day Service in St. Clement's Anglican Church in Balzac, Alberta, I intend to use the stories from "Changed by War," which many of my parishioners will never have heard before. Many thanks to Alice Taylor for her contribution to this fine magazine.