The Einstein Camera

A century ago, a U of T astronomer led a small group of Canadians on a daring expedition to remote Australia. Their mission? To prove the Theory of General Relativity

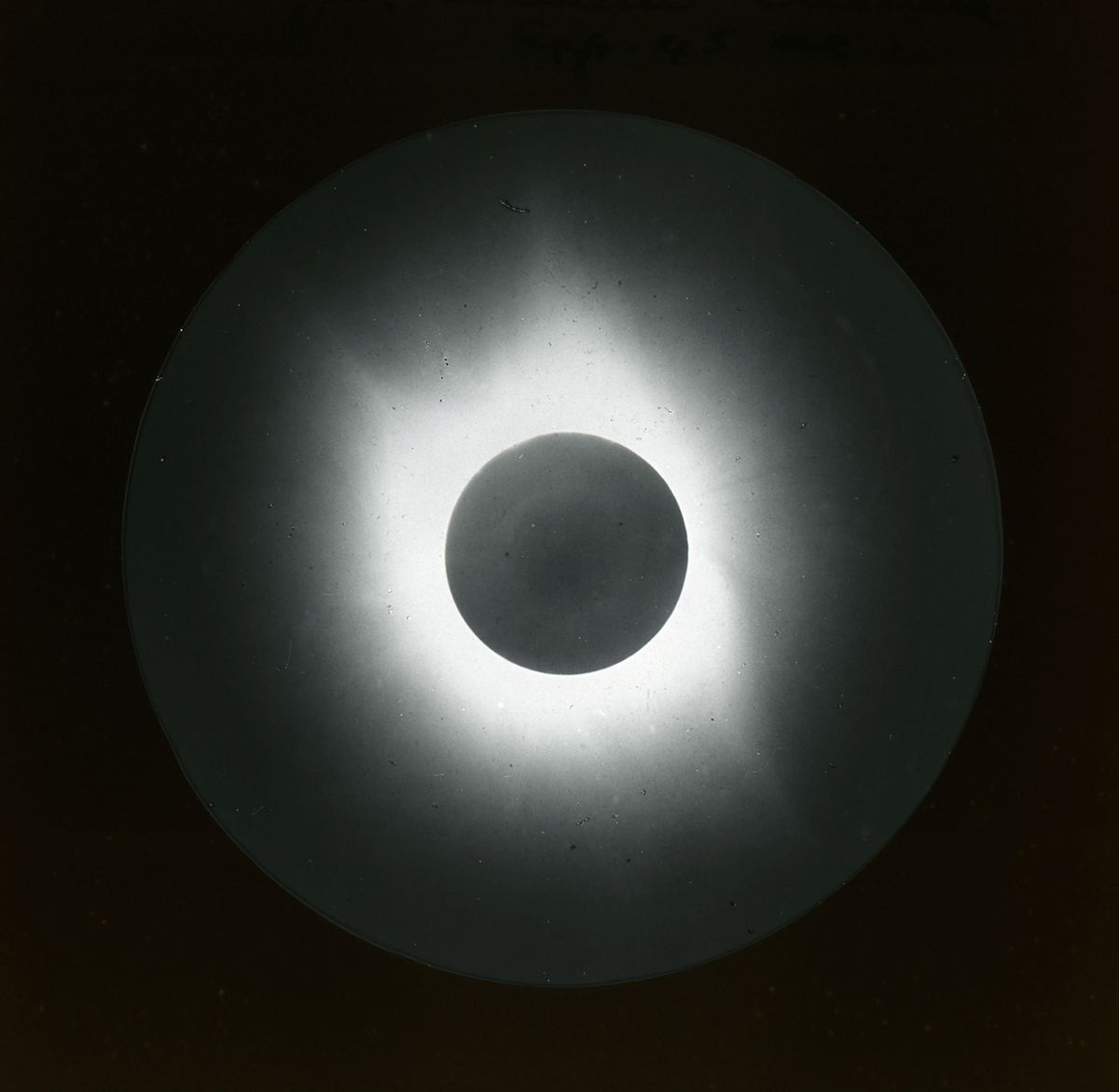

When Einstein put forward his new theory of gravity in 1915, the scientific community reacted cautiously. Its predictions had to be tested. Einstein’s theory, known as general relativity, predicts that a beam of light that passes by a massive object ought to be deflected. Light from a distant star, for example, ought to bend as it passes our sun. To measure this bending, you need to blot out the overwhelming light from the sun – luckily, this happens naturally during a total solar eclipse. British astronomers were able to observe the May 1919 solar eclipse, and at a meeting in London that fall, they announced that the results were consistent with Einstein’s predictions. Newspapers picked up the news, making Einstein a superstar.

But those early results were not accurate enough to be definitive. Astronomers needed more data – which meant mounting an expedition to the next suitable eclipse, due on September 21, 1922. The “path of totality” of that eclipse would trace a line from eastern Africa across the Indian Ocean and finally across Australia, where weather prospects were most favourable.

Among those eager to go was Clarence Augustus Chant, the head of U of T’s astronomy department. Chant, the foremost astronomer in Canada at the time, was keen to assemble a Canadian team to test Einstein’s theory. This was no small task for a Canadian scientist in the early 1920s, but Chant was well connected. He was able to shore up the necessary financial and scientific support to allow him and a small contingent of Canadians to join an expedition led by William W. Campbell of the Lick Observatory in California. The combined U.S.-Canadian team would head to Wallal, on Australia’s northwest coast, while two separate Australian teams and one from Britain would head to other viewing locations along the path of totality.

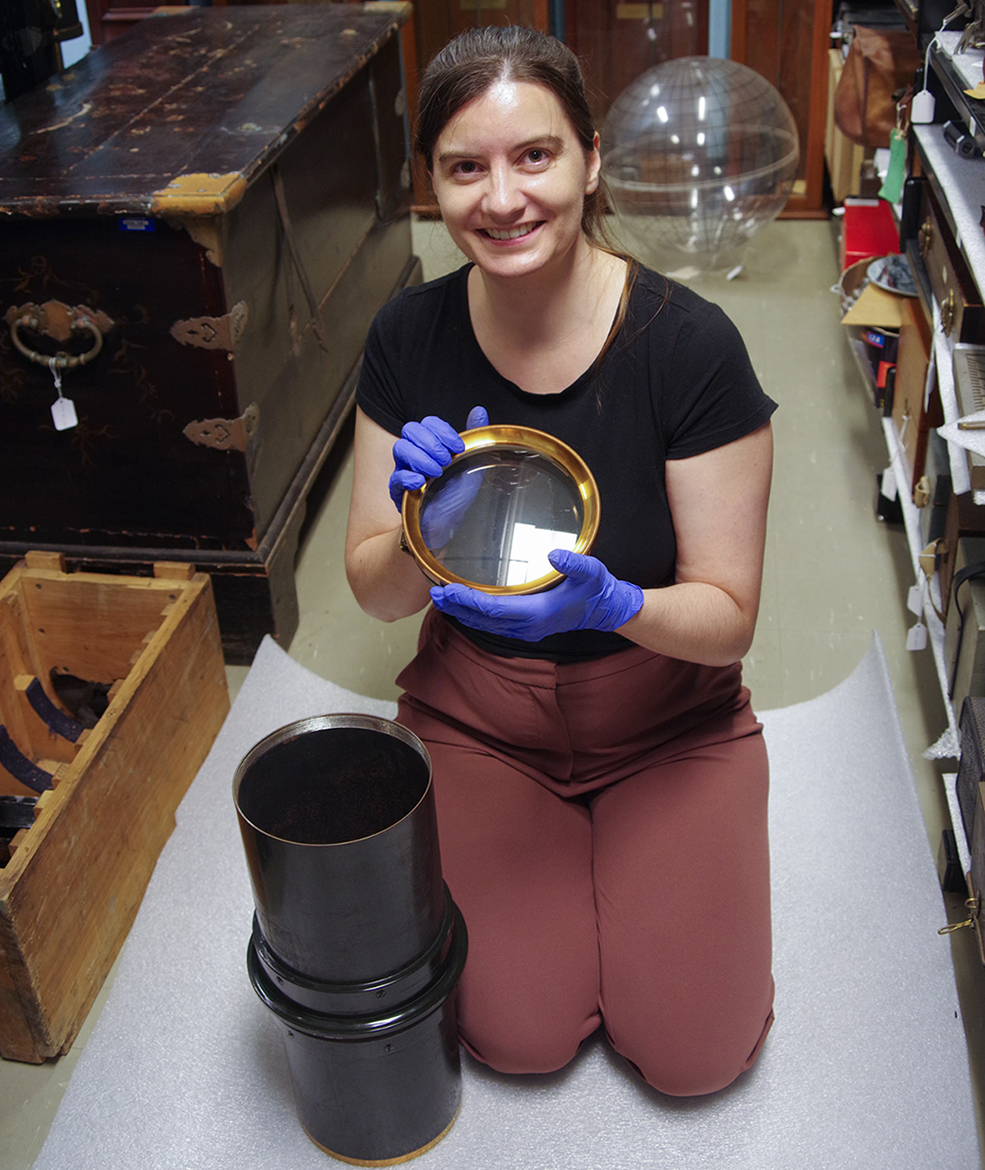

For Chant, it would be the trip of a lifetime, requiring months of planning and specialized equipment. This included the so-called “Einstein camera” – a telescope, essentially, with a specially-made six-inch-diameter lens at one end and a photographic plate at the other. The camera was intended to record light from faint stars near the eclipsed sun. Designed by C.R. Young, a U of T engineering professor, and largely constructed in Toronto, this equipment would be key to the expedition’s success.

***

The Canadian team set off for Australia on June 7, 1922. The group included Chant’s wife, Jean Chant, his daughter Elizabeth Chant, a recent U of T graduate and future nutrition scientist, and Reynold Young, a government astronomer. They traveled first by train to Victoria, B.C. and then across the Pacific via steamship, arriving in Australia in mid-August. There, along with members of the other expeditions, they were feted by Australian dignitaries on a cross-continent rail trip, and then escorted by the Australian navy to Wallal.

The eclipse party arriving at Wallal consisted of 35 people. Joining the American and Canadian teams were representatives from New Zealand and India, and 10 members of the Australian navy. Greeting them on land were local Indigenous Australians, the Nyangumarta people, who assisted with the difficult task of unloading the ships and moving more than 35 tons of heavy equipment and supplies across an expanse of shallow water to camp.

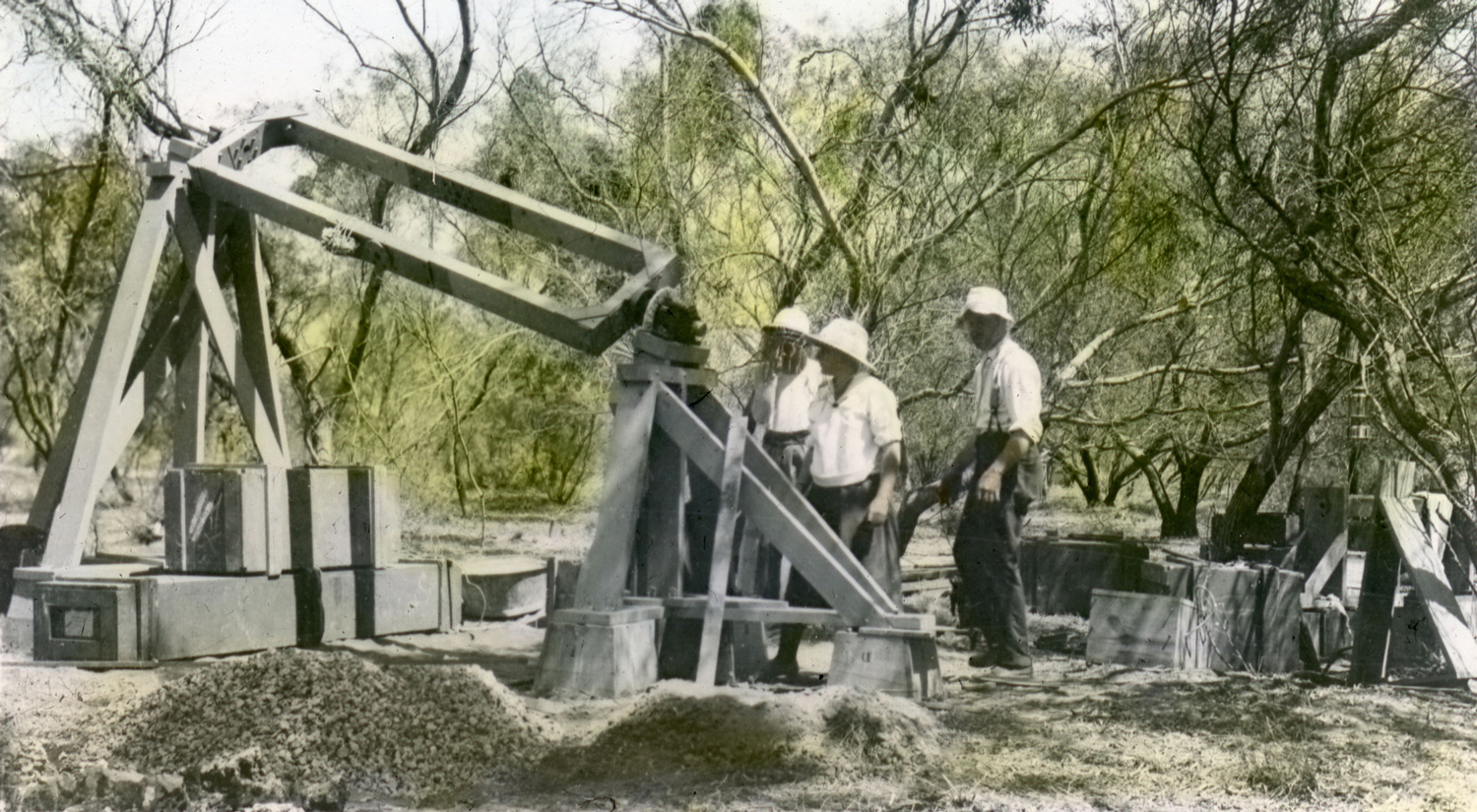

The scientists had three weeks to prepare for the eclipse and would need every single day. With the support of the navy and Nyangumarta people, concrete piers were built, tents put up, wooden structures erected, and equipment unpacked and calibrated. Fine dust plagued everything – delicate equipment had to be wrapped in cloth to keep the dirt at bay. Chant reported that the Nyangumarta people carried water in kerosene cans to the camp to dampen the sand – support that continued throughout the scientists’ month-long stay.

The teams faced other problems, such as a temporary breakdown in radio communications, crucial for picking up wireless time signals to calibrate the camp chronometer, which would be used for measuring the precise time of the eclipse. But the mood at camp was collegial and convivial – the teams took meals in “Café Einstein,” and worked together to solve instrument problems, and the Nyangumarta people demonstrated fire-starting techniques and the use of a boomerang. In the evenings, there was singing and dancing.

By Eclipse Day, the Wallal camp boasted an impressive array of telescopes, including the all-important Einstein cameras – four from the U.S. and one each from Canada and India. The 11-foot-long Canadian device, designed to turn by clockwork to follow the stars as the Earth rotated, could also be guided by a person pulling delicately on a length of fishing line attached to the gears. The British expedition and two Australian teams had their cameras at different camps. Towering over everything at Wallal was the 40-foot American corona camera, designed to photograph the sun’s wispy outer atmosphere.

The observers prepared for other types of measurements, examining the unique phenomena associated with a total eclipse. In the Canadian party, Elizabeth Chant was to take images with a polariscope – an instrument for measuring the polarization of light – and Jean Chant was to make observations of the so-called “shadow bands” – parallel, undulating shadows seen at the beginning and end of a total eclipse.

The astronomers planned the exposures down to the second. They would have to open and close shutters and exchange photographic plates by hand for every photo they took. James Kean, from the Australian navy, had the crucial but unforgiving task of keeping an eye on the chronometer and shouting out passing seconds – 1, 2, 3 – so the scientists could time their work precisely.

September 21 dawned perfectly clear. The teams counted down the minutes to totality, expected at around 1:27 p.m. William Campbell, at the 40-foot camera, had the honour of shouting “Go!” Kean started counting, and the observations began.

Disaster struck the Canadian team immediately. The fishing line used to drive the telescope mounting, replaced only that day, snapped seconds into the eclipse. Chant later recounted the moment:

We were horrified! Were we going to lose all our effort? [Reynold] Young had never failed in any emergency. With great skill he repaired the cord and replaced it round the rod, but we had lost many precious seconds. Hastily deciding on exposures, we secured one plate at 9 [seconds] and two at 45 [seconds]…

In the end, only half the teams, including the Canadians, obtained useful images, with equipment difficulties stymying half the attempts. Everything had come together – the weather was clear, the camera structure moved as designed, the lens produced a crisp, focused image of sufficient quality and size, and last-moment catastrophe was averted. The two precious 45-second plates were developed in a makeshift darkroom and were transported with extreme care alongside the expedition team back to Canada.

Then came the months-long measurements and calculations needed to compare the positions of stars in the eclipse images to those taken earlier as controls. As U of T lacked the necessary measuring equipment, Young did this work with a colleague at the Dominion Astrophysical Observatory in Victoria, B.C. Chant and Young announced their findings ahead of the other teams. The result was not decisively Einsteinian, but it was closer than the 1919 results. Chant declared the outcome was “in harmony with the amount predicted.” The Americans followed shortly, with similar conclusions, and newspapers once again told the world. (“Einstein Theory Satisfactorily Proven,” as the Ottawa Evening Citizen put it.)

***

Astronomers continued to pursue solar eclipse images to test relativity through the 1950s, eventually shifting to radio waves instead of light, since radio waves are not affected by atmospheric turbulence. Every such experiment to date has yielded further support for general relativity.

The U of T Einstein Camera itself had an encore in 1932 when Chant, again with Young – by then a U of T professor himself – mounted another eclipse expedition, this one only needing to go so far as a Quebec hilltop. Sadly, that attempt was clouded over. But Chant successfully leveraged attention from the extraordinary Australia expedition to pursue his long-term goal of establishing an astronomical observatory for U of T, which opened in Richmond Hill, Ontario, in 1935.

A diarist and keen photographer, Chant left behind a detailed account of the trip, along with dozens of his photographs, which survive in the U of T Archives. However, of the tons of equipment hauled to Australia and back, only the U of T Einstein camera lens, carefully preserved by Chant, survives. Packed in a wooden crate lined with crumpled 1920s newspaper, its optics in near-perfect condition, it rested for decades, virtually forgotten, at the David Dunlap Observatory and later in the historical artifact collections of the David A. Dunlap Department of Astronomy and Astrophysics. Only recently re-identified as the lens from the 1922 Einstein camera, this unique artifact bears witness to an epic story of early Canadian scientific ambition, and the plucky U of T team who – against the odds – secured a place in the history books.

This episode from Canadian history will appear in an upcoming feature documentary titled Bending Light, directed by Alan Goldman. The film tells the story of the 1922 expedition and features the surviving Einstein camera lens, as well as interviews with several current U of T faculty members and staff.

Dan Falk (@danfalk) is a science journalist based in Toronto. His books include The Science of Shakespeare and In Search of Time. Victoria Fisher is the assistant curator of the University of Toronto Scientific Instruments Collection.

No Responses to “ The Einstein Camera ”

Thanks so much for this. It was fascinating to think of all the things we now take for granted that they didn't have - from transport to atomic clocks. And so appropriate on this day of another eclipse.

U of T, keep up the groundbreaking and challenging work! Bravo.

I can fathom how interesting this trip was. Bravo to the Chants and Prof. Young!