A century before the First World War, the main weapon of the War of 1812 was a muzzle-loading musket that fired up to four shots a minute to a distance of roughly 90 metres. The machine guns used on the battlefields of the First World War could fire hundreds of rounds per minute with a range of several thousand metres. The weapons of modern warfare mangled tissue and fractured bone, creating the perfect conditions for infection and disease. Many soldiers fighting on the “tetanus-laden” battlefields of Belgium and Northern France became infected with tetanus (also called lockjaw), which had a mortality rate of between 40 and 80 per cent.

In 1914, 32 per cent of the British wounded contracted tetanus. Taken by surprise by the high rates of infection, the British and Allied command looked to Canada and the University of Toronto for help. Dr. John FitzGerald – U of T Medicine graduate, faculty member and public health pioneer – played a critical role in preventing tetanus and other infectious diseases in the Canadian and allied armies.

In May 1914, at FitzGerald’s urging, the university took over the fledgling antitoxin laboratory that he had established a year earlier in a backyard stable at 145 Barton Avenue, near the intersection of Bloor and Bathurst streets. FitzGerald opened his lab using $3,000 of his wife’s inheritance. With new equipment, a hired technician and five horses he began producing safe and inexpensive diphtheria antitoxin that would eventually be made available to all Canadians, regardless of class or income.

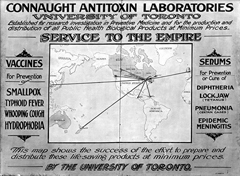

After war broke out, military demand for antitoxins and vaccines prompted FitzGerald to move his lab to a farm donated by brewer and philanthropist Albert E. Gooderham. The lab would eventually become the world-famous Connaught Antitoxin Laboratories. U of T President Robert Falconer and U of T’s board of governors approved a plan for the laboratory to produce enough tetanus antitoxin for every Canadian soldier at a much-reduced rate. In a message to Prime Minister Robert Borden, Falconer characterized it as the university’s “patriotic duty that we in Canada should manufacture tetanus antitoxin for our own expeditionary forces.”

The expanded labs produced a host of life-saving medication for the war effort, including tetanus antitoxin, anti-typhoid vaccine, diphtheria antitoxin, anti-meningitis serum and smallpox vaccine.

By the war’s end, vaccines and the practice of giving wounded soldiers tetanus shots had reduced the rate of infection to 0.1 per cent, making the anti-tetanus program one of the most successful health campaigns in wartime medicine.

Recent Posts

People Worry That AI Will Replace Workers. But It Could Make Some More Productive

These scholars say artificial intelligence could help reduce income inequality

A Sentinel for Global Health

AI is promising a better – and faster – way to monitor the world for emerging medical threats

The Age of Deception

AI is generating a disinformation arms race. The window to stop it may be closing