“Those who have had a dream and have lived to see that dream come true will have some conception of my feelings when I first entered the Mexican forest and there, before my eyes, was the realization of a dream that had haunted me since I was 16.”

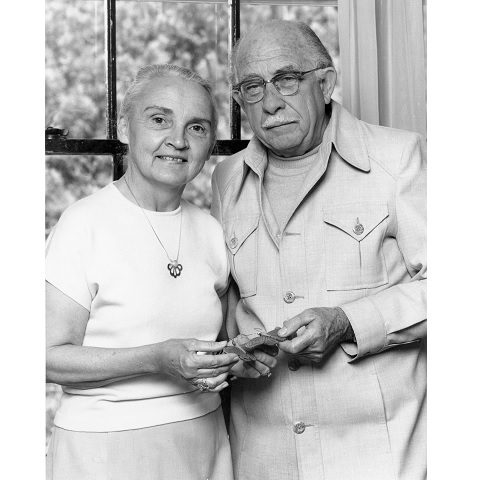

This is Fred Urquhart writing about discovering the place where millions of monarch butterflies go to wait out the winter, a place that he and his wife Norah spent over 70 years between them trying to find. In the winter of 1975, a researcher working for them at last located it: the small Mexican highland retreats where these butterflies congregate each year, after completing epic journeys from as far as 5,000 kilometers to the north.

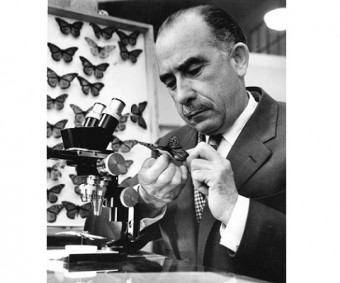

Fred and Norah, both deceased, were long attached to the University of Toronto’s Scarborough campus, Fred as a popular zoology professor whose lectures were sometimes broadcast on CBC television, Norah as a researcher and writer. “I met them when I was starting out my career,” recalls Ian Brown, a neuroscience professor. “It is rare what they pulled off. As a boy, Fred had set himself a particular big question – where do these butterflies go in the fall? – and, after some setbacks, with great creativity, he and Norah finally solved it.”

Fred grew up near a railway line on Toronto’s fringes, and became fascinated with the orange and black butterflies supping and laying their eggs on the copious milkweed near the tracks. In 1935, at the Depression’s height, he completed a BA in biology at U of T, followed by an MA (1937), a PhD (1941), and a job curating the Royal Ontario Museum’s insect collection. After serving in the meteorological service in the Second World War (on the Prairies), he returned to Toronto, married Norah, and joined the university’s staff. Norah herself earned multiple degrees from the university: a BA in 1941 (Victoria) and a social work diploma in 1943.

In a recording of an interview stored in the university archives, Fred speaks of their painstaking efforts to come up with a tag that would stick to a monarch over its migration, but not impair its ability to fly. After several failures (using paint, or labels that were too heavy or came off in the rain), they found that price stickers made to adhere to glassware worked.

Through trial and error, they learned to scrape some scales off the lower section of a wing near the body, and fold the sticker around the wing-edge. Campus legend has Urquhart biking around with tagged butterflies tied to his handlebars with thread, seeing if they could fly with the tags. The Urquharts printed their office address on each sticker, so that butterfly sightings could be reported.

Norah strategically placed articles about their project in as many papers and journals as possible, and they roped in a group of what they called citizen scientists from across the continent to help. “It was unusual then to use ordinary people in scientific work,” says Scarborough biology professor Marc Cadotte.

Don Davis, one of the core members of the Insect Migration Association founded by the Urquharts, once tagged 7,000 butterflies in a single year and says: “Many of us became lifelong friends. They plotted the findings on a map in their Scarborough home – ‘Butterfly Central’ we called it, with all the lines heading south, and west, towards what?”

They soon ruled out an early theory that the population of butterflies that fluttered around Eastern North America wintered on the Monterey Peninsula in Northern California. “That place was already well-known, but the numbers didn’t add up,” says Davis, a social worker. “Too few butterflies went there.”

The Urquharts took a sabbatical and drove all around southern Texas – “we put 32,000 kilometers on that car,” he says in an archival recording – but it seemed the butterflies were transiting through the Lone Star State, not stopping. Norah placed another request for assistance in a Mexican newspaper, and a rogue inventor-adventurer named Kenneth Brugger responded. With tips from the Urquharts, in 1975, Brugger and his wife Catalina eventually located the wintering spots on some volcanic mountains not far from the Sierra Madre range, in the Michoacán province. The next winter the Urquharts visited in a trip described in a cover story for National Geographic.

“The stillness of the air, the damp, somber darkness of the forest, the blue-gray beams of light like ethereal pathways to the blue of the heavens above, all gave the impression of a cathedral where one should converse in whispered tones for fear of breaking the enchantment.” – Fred and Norah Urquhart, The Monarch Butterfly: International Traveler. Photo: screenshot from IMAX film Flight of the Butterflies

“Norah and I are no longer young,” Fred wrote. “As we walked along the mountain crest, our hearts pounded and our feet felt leaden. The rather macabre thought occurred to me: Suppose the strain proved too much?” But it didn’t, and there the monarchs were: “Butterflies – millions upon millions … They clung in tightly packed masses to every branch and trunk of the tall, gray-green oyamel trees. They swirled through the air like autumn leaves and carpeted the ground in their flaming myriads on this Mexican mountainside.” Near him, a branch broke off, releasing a cloud of butterflies, and, lo and behold, one of them had a tag on it – it had been adhered by a schoolboy in Minnesota.

The discovery provided a happy ending to the Urquharts’ joint quest – but it also marked a beginning of sorts.

The Urquharts’ work with the public has started a movement that continues to try to protect the monarchs from the assorted threats they face.

The Insect Migration Association has morphed into Monarch Watch, a Kansas-based non-profit that organizes tagging, monitors yearly numbers, and sells milkweed for gardens. “It’s tough times for the butterflies,” Monarch Watch’s head scientist, Chip Taylor, says. “Industrial agriculture is threatening the flight path that the Urquharts so painstakingly mapped. Herbicides kill off milkweed, which they need, and insecticides get many of the butterflies en route. We’re working with North American Free Trade Agreement officials to try to get a monarch migration corridor protected.” Mexico has made a preserve of the monarchs’ winter getaway – but each year loggers illegally take down some of the pine species on which the monarchs like to hang.

In the monarchs’ summer breeding grounds, in Canada and the US northeast, Cadotte notes that a species of milkweed brought over from Eurasia, the Dog Strangling Vine, attracts the butterflies, but can’t sustain monarch caterpillars. “It’s everywhere, it’s hard to remove,” he says, “and it tricks the monarchs into laying there.” In his lab, Cadotte is looking into whether the release of a Ukrainian moth that likes to eat this species of milkweed might limit its spread.

The Urquharts’ work also opened up further avenues of research: scientists have since been investigating, for instance, how exactly monarchs navigate on their long journeys (the latest findings have them making use of both the earth’s magnetism and the sun’s position) and whether the viceroy butterfly evolved to resemble the monarch, because monarchs are toxic to most birds.

The continuing relevance of the Urquhart’s work was one thing that recently led two U of T grads to make a film about their quest, 2012’s IMAX film, Flight of the Butterflies. Its co-writer, Wendy MacKeigan (MA 1977) comments: “We opened the film with a quote from Darwin about evolution being written on the wings of the butterfly.”

Her husband, Jonathan Barker (BA 1973 UC), the film’s producer, expands on its relevance: “That mimicry of the monarch by another butterfly, the viceroy – that’s a key aspect of the science of evolution.”

After seeing the film, the Urquharts’ former colleague Brown sought to have the university mark their accomplishment. “It was one of the 20th century’s great discoveries in this field,” he said. “We thought it should be remembered with something tangible, and so it was decided to set up a butterfly-friendly garden on the Scarborough campus.”

The garden was opened last fall, with the release of some monarchs, who at once set about feasting on the right kind of milkweed before a crowd of academics, administrators, old members of the Urquharts’ circle and a slew of schoolchildren.

The filmmakers also attended. “When I was working on the film,” MacKeigan recalls, “as often as not the words found by the Urquharts were the best ones. He described the butterflies that obsessed him as these ‘fragile, wind-tossed scraps of life.’ It had poetry, and his feeling for them wrapped up in it – of course, we had to use it.”

Watch the trailer for Flight of the Butterflies:

Video by Flight of the Butterflies

No Responses to “ The Scientists Who Found the Monarch Butterfly’s Hidden Realm ”

My father, Bill Galbraith, was a U of T grad (Chem Eng 1948) and one of his best friends was Frank Stricker, one of the big network of volunteers recruited by Dr. Urquhart in the 1950s and 1960s. The butterfly study was very much part of the landscape of our family cottages, next to each other, just south of Kincardine, Ontario.

There is a lovely butterfly garden in Dundas, Ontario, named the Urquhart Butterfly Garden in honour of the Urquharts, too. It is a community initiative - very grass-roots - and a magnificent place.

Fred and Norah were my maternal uncle and aunt. Their son, Doug, is my cousin, two years my junior.

I have many happy family memories of Uncle Fred at home in Highland Creek, in his office at the Royal Ontario Museum, in his lab with Aunt Norah pinning butterfly finds on a map of North America, and in his new lab at Scarborough College with all the cocoons attached to growing milkweed plants.

I remember also the lecture he gave at Convocation Hall at which his mother, my grandmother, was present and at which he ate a monarch butterfly, pronouncing it to taste like dry toast, the latter in an attempt to dispel the theory of Batesian mimicry.

Thank you very much for this article. It brings back happy memories and family pride in Uncle Fred and Aunt Norah's remarkable accomplishments.

Loved the article as I lived through the discovery with Professor Urquhart and Norah as an Insect Migration Associate in the early '70s. After the discovery of the overwintering site, I contacted the professor because I just wanted to hear him tell me about his visit to the site. He did tell me that he went against doctor's orders and the trek up the mountains was so draining on his health and “what if my life’s work may never be realized to see the amazing overwintering site”! I treasure the book by both him and Norah, which he autographed. I have never stopped raising monarchs and have given countless lectures to business women’s groups, church groups and mostly school classrooms, and was deemed The Butterfly Lady at our Harrisburg PA’s Museum of Scientific Discovery back in the late '70s. My children, grandchildren, our neighbours and friends look forward to raising the monarchs every year.

I read a book a long time ago entitled The Travels of Monarch X. It greatly inspired my sons and me. In fact, I even composed a song about what the Urquharts accomplished. I also saw the excellent movie Flight of the Butterflies at the Ontario Science Centre. These pioneering efforts of the Urquharts changed our lives!