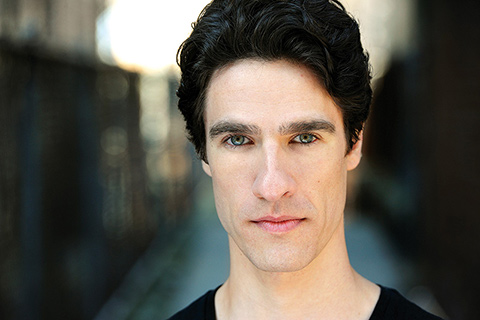

Ben Mehl (BA 2007 UC) discovered two life-changing things about himself in his graduating year as a drama major: he was likely a good enough actor to make a living at the craft, and he had a genetic disease that could prevent him from even trying.

“I had a role in my first Hart House musical, and it was a magical experience,” says Mehl, 31, now a theatre and film actor in New York. “It was where I realized that I could bring joy to people, and that I should keep doing it.” But during those performances of the spoof hit Reefer Madness something strange was happening with his eyes. “It was like when a flash goes off and you have that dot in your vision. Except mine never went away.”

Diagnosed with Stargardt, a rare form of macular degeneration that causes unpredictable vision loss, Mehl was afraid he would never act again. But he eventually attended New York University’s graduate acting program. At the time, he was coming to terms with losing much of his central vision. “I started on a journey of learning what it means, practically and artistically, to be an actor with this disability.”

Before grad school, Mehl had also developed blind spots in both eyes. He learned to look an inch above a person’s head and use his peripheral vision – which is intact – to see their face and eyes. Mehl keeps a tablet on hand to enlarge text so he can read scripts – and, more important, he stopped looking at his disease as a liability. “It’s actually valuable currency in terms of what an actor’s job is – to connect to what it is to be human.”

These adaptive skills have helped Mehl land roles in off-Broadway productions, in theatres across the U.S. and in several independent films. He has also conducted drama workshops in prisons and homeless shelters, and, through the 52nd Street Project, created original theatre with inner-city kids – using the beatboxing skills he refined as a member of Onoscatopoeia, the Hart House Jazz Choir.

This year, Mehl hopes to make his directorial debut in a small New York production of a Shakespearean comedy. His sight has been relatively stable for several years. “I don’t know how it will progress, but I’m no longer fearful,” he says. “I don’t have this idea of the way my life is supposed to go, and that my disease is something that will prevent me from achieving that. I’m curious about the infinite spectrum of possibilities.”