In 1961, Edna Staebler – writer, homemaker and future cookbook author – was suffering the sort of black misery that comes from divorce. Her husband of 28 years had told her their marriage was over. He was leaving her to marry one of her best friends – the woman she had confided in about her husband’s drinking, the unkind words he hurled at her while drunk, his constant philandering. The couple had no children; they hadn’t had sex in the past 22 years. Staebler was 55, with precarious employment as a freelance writer. She thought she would grow old alone, impoverished and unhappy, and that her best years were behind her. She cried herself to sleep every night for a year.

Then, the tears stopped. The best years of her life were soon to begin.

Staebler’s life-changing moment came at the age of 60, when an editor asked her to write a Mennonite cookbook. Staebler (BA 1929 UC) had just published a collection of her articles about the Mennonite and Amish in her hometown of Kitchener-Waterloo, Ontario. One of her best-known pieces, which ran in Maclean’s, was “How to Live Without Wars and Wedding Rings.” In it, she captures the pleasures of simple family life and the beliefs of Old Order Mennonites by richly detailing the lives of Bevvy Martin and her family.

Staebler wrote about Bevvy again in Food That Really Schmecks, recording her recipes – as well as those of other Mennonite women and Staebler’s own mother – for the cookbook. But what differentiated Schmecks from other cookbooks, and turned it into a classic, was Staebler’s storytelling. Woven between the recipes of Mennonite comfort food – shoo-fly pie and grumbara knepp (potato dumplings); apple fritters and kraut wickel (cabbage rolls) – are stories of Bevvy in her fieldstone farmhouse who “is always busy schnitzing (cutting up apples for drying)” and who has her recipes in “a little handwritten black notebook, well-worn and some of its pages spattered with lard.” Schmecks – first published 50 years ago – sold tens of thousands of copies upon release, which was an incredible number for Canada in 1968. A commemorative edition was released in 2006 by Wilfrid Laurier University Press, shortly after Staebler’s death.

By Staebler’s own admission, she had “no qualification for writing a cookbook except that I was brought up and well fed in Waterloo Country.” (In fact, in her 60s, she owned only two cookbooks: a Betty Crocker classic and a Mennonite one, both gifts.) But she didn’t need to be a chef: it was her ability to use food as a storytelling vehicle to evoke home and hearth, and to open a window into the houses of others, that drew readers. Through her recipes and stories on comfort food, she was offering emotional sustenance. “I think she popularized the Canadian cookbook,” says Veronica Ross, who wrote the biography To Experience Wonder: Edna Staebler, a Life (2003). “They’re for people who like good food with simple ingredients. The recipes are not 25 steps, and she would sometimes say, ‘If you don’t have the ingredient, just go on.’ The stories just made you feel good about life.”

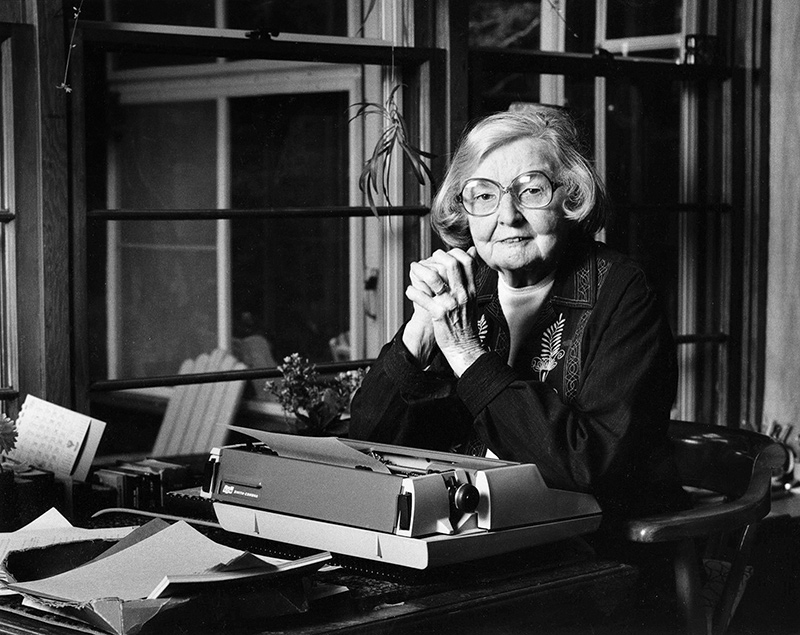

While Staebler was best known as a cookbook writer, she didn’t always embrace the role. At first, she was embarrassed to talk about working on recipes with her writer friends (although that would change, when she realized how much happiness readers derived from Schmecks). She also faced stereotypes: there was a tendency for the public to pigeonhole her as a docile, grandmotherly, stay-at-home cookie-baker – likely something many female cooks and food writers of her generation faced. “She always said, ‘I’m not just a sweet dumpling of a cookbook writer,’” says Ross, noting that Stabler was very independent – and feisty when it came to pushing publishers on matters of marketing and royalties. “She was approachable, but she was very intelligent and astute.”

Her independent streak showed early, at U of T. While it wasn’t the norm for women to attend university in the 1920s, Staebler was determined to see life beyond Kitchener-Waterloo. She enrolled in the general arts program at University College, wrote for the Varsity, attended dances at Hart House and stayed in Queen’s Hall residence. (Alas, it was also here she made friends with Helen MacDonald – the woman who, almost 40 years later, would run off with her husband.) “Her U of T days were totally liberating,” says Ross. “I have to say her grades in high school were terrible and sometimes she had to repeat courses: I think she just needed that university experience to make her think and to expose her to a wider world.”

Staebler’s list of published books grew throughout her 60s, 70s and 80s. Her favourite, Cape Breton Harbour – set in the fishing village of Neil’s Harbour in Nova Scotia – was released in 1972, two decades after she first sought a publisher for it. She wrote More Food That Really Schmecks and Schmecks Appeal. Her last book, Haven’t Any News: Ruby’s Letter from the ’50s, was published when she was 89. She also established the Edna Staebler Award for Creative Non-Fiction in 1991, which has helped Canadian writers from Charlotte Gray to Wayson Choy.

Staebler died at the age of 101, peacefully in her sleep, at a nursing home in Waterloo. “I think Edna is an inspiration not just for what she did at her age, but how she did it and how she lived her life,” says Ross, who noted that Staebler chose not to be bitter about her marriage, but to see the wonder in every day. “She had a lot of life experience, but she had the eyes of a knowing child – meaning she found something fresh all the time.”

In a diary entry from July 17, 1991, when Staebler was 85, she broke her life into a trilogy: “The first twenty-eight were difficult, searching years, trying to find who I was, not at all sure of my identity. The twenty-eight married years were more difficult, trying to live Keith’s life and cope with his alcoholism and both our insecurities. The last twenty-eight years I’ve been living my own way and loving it and being creative, having fun and many friends and readers who love my books.”

“I regret none of it.”

No Responses to “ Finding Comfort in Food ”

I have printed out your wonderful article, and have pasted it into my copy of Schmecks. Thank you.

I can't remember the year, but Edna endowed the Kitchener Public Library with funds to appoint a writer-in-residence. I worked at the library at the time and made a yearly visit to her cottage/home on Sunfish Lake to discuss who might be offered the posting. Over the years, Edna and I became friends. The library hosted her 85th birthday with a grand party that drew authors Pierre Berton and Doug Gibson, and an auditorium overflowing with more than 200 fans. I served on the inaugural board of The New Quarterly -- the literary magazine that she, Harold Horwood and Farley Mowat launched in 1981. A memorable fundraiser, the Edna Staebler Golf Classic, held in October 2006, went ahead as planned even though Edna died on Sept. 12. We all felt she would have wanted that.

A very interesting article!

This is a wonderful and interesting article! I liked it very much.

I am going to search out her books. I have many things in common with Edna, and I wish I had known about her earlier. It might have been comforting when I was at my lowest. Thank you for writing this article. It was very interesting.