Hidden Tales of Ancient Books

U of T researchers are using advanced technologies to reveal new insights about texts that are hundreds of years old Read More

For many people, the story of the book starts with the Romans, climaxes with Gutenberg and slithers to an ignominious finale with Silicon Valley and the e-reader. The folks at The Book and the Silk Roads research project offer a different version of this tale.

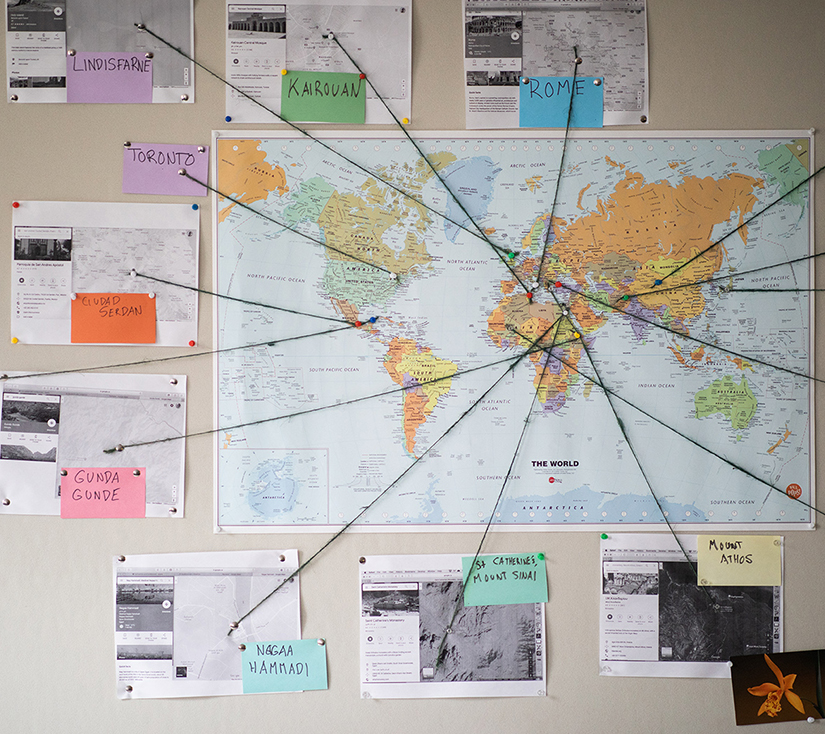

Created three years ago as part of a larger project at U of T called the Critical Digital Humanities Initiative, the 60-odd collaborators who make up The Book and the Silk Roads group use a mix of humanist smarts and digital sleuthing to uncover alternative histories of book culture, especially their more pre-industrial, non-Western iterations.

They’ve used peptide analysis on the adhesives of pre-modern books, a microscope on a 10th-century prayer sheet from Dunhuang (in what is now northern China), and a medical imaging technology on the interiors of books otherwise too precious or fragile to open.

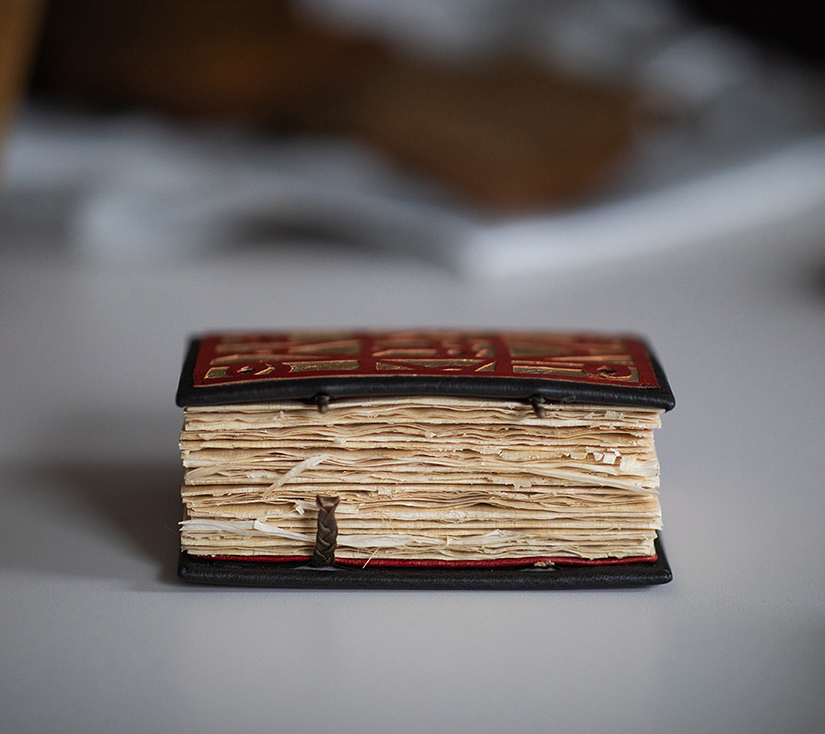

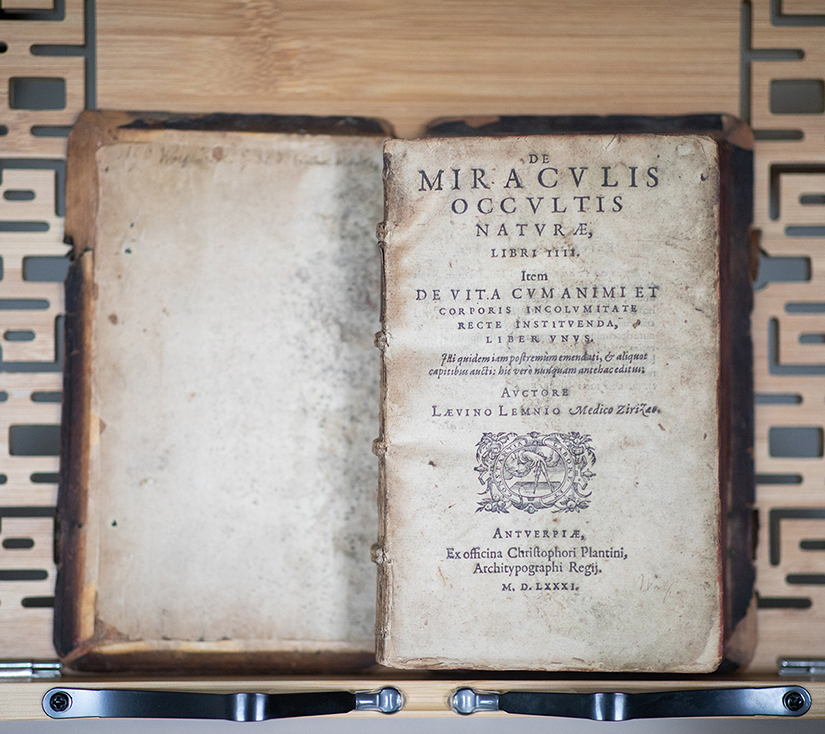

In one of the network’s first experiments with micro-CT scanning, using a late 15th-century liturgical book from France, they spotted what they call a “ghost binding” – the cuts and holes left behind by the text’s previous binding. For Alexandra Gillespie, a professor of English and Medieval studies at U of T Mississauga and the lead researcher on the project, it was an “aha” moment – proof that advanced technologies could reveal previously unknown details of a book’s history and structure. Other scholars have used CT to uncover text hidden within books too fragile to be opened in the conventional way.

For Gillespie, the book itself – its physical incarnation – is at least as interesting as the text it contains. Old books are time capsules, says Gillespie, “examples of how human beings learned hundreds and hundreds of years ago. They’re really precious, right down to their string and their glue.”

Even their smallest details can tell us much about the way materials and technologies travelled about the pre-modern world. “When one culture comes up with an innovation on how to do something,” says Gillespie, “it is remarkable how it moves.”