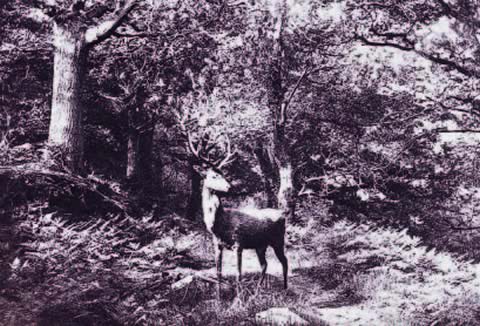

Look closely at the deer in this photograph, taken in 1852 by John Dillwyn Llewelyn in the woods around his estate. Notice anything unusual?

The deer is actually stuffed, says Matthew Brower, a professor of museum studies and the author of a new book about early American wildlife photography.

See photographs by pioneering photographer John Dillwyn Llewelyn

While the modern viewer might consider this “faked” wildlife photography, taking pictures of a taxidermied animal in a natural setting made sense at the time as a means of representing “wild” animals, says Brower. “There was no sense of animals as part of a healthy habitat. The deer was simply an accent for the landscape.” Llewelyn wouldn’t have been able to capture the image of a live deer, even if he had wanted to. Cameras didn’t have shutters and exposures lasted at least a minute. A wild animal wouldn’t have stood still for even a fraction of the time required.

Brower’s book, Developing Animals, looks at how photographing animals has changed through time, and how it has altered the way humans relate to animals. “We’ve come to see wildlife photography as ‘true’ representations of live animals in nature, and we think it’s always been this way,” says Brower. “But it hasn’t. Our thinking has evolved.”