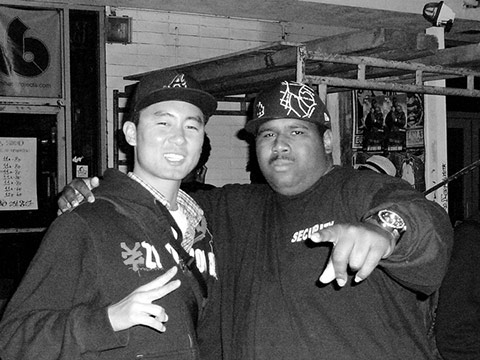

Between 2005 and 2009, Jooyoung Lee spent most Thursday nights at Project Blowed, a weekly open mike for aspiring hip-hop artists in south central Los Angeles. Lee, who at the time was working toward his doctorate in sociology at UCLA, had originally planned to write about Project Blowed. But, over time, he became interested in how many of the youth involved with the project began to see their artistic pursuit as a career path, a creative alternative to gang life. They started putting their energy into being discovered, or “blowin’ up.”

Lee, now a U of T sociology professor, collected thousands of pages of field notes, 90 hours of video recordings and interviewed 30 rappers. The resulting book, Blowin’ Up, shines a light on the lives of young black men growing up, as Lee writes, “in the shadows of gang violence and the entertainment industry.” It delves into L.A.’s hip-hop culture and the creativity of rapping. And it opens a window into a part of the city where neighbourhoods are divided by gangs and most people’s lives have been touched by violence.

Critics of hip hop say – often without evidence – that it funnels youth into gangs and leads to increased violence. But Lee found the opposite. “The young men I met and followed saw hip hop as a sanctuary – a respite from the street life,” he says. “It provided a context where they could meet and befriend youth from different neighbourhoods.”

Lee’s research also overturns a stereotype that young black men who pursue rap dreams aren’t planning for the future. In fact, says Lee, these men resemble most other entrepreneurial youth. The difference lies in how they are viewed, and that they lack the safety net of a well-to-do family. “There’s a cultural expectation that bold and industrious people in their 20s will take a business risk, go travelling or chase an unlikely career in the arts,” he says. “But we have a very different standard when we talk about young black men from working-class backgrounds. There’s this assumption that they shouldn’t do these things; they should just focus on a pragmatic way of making ends meet.”

With his book, Lee hopes to spark discussion about this kind of implicit racism, and about support for the arts in disadvantaged communities. He says many North American cities, including Toronto, have turned to punitive measures for dealing with “youth problems” – such as putting more police on the street. While he acknowledges that police are vital, he argues that the arts offer a proactive way of dealing with the same issue, and cites Project Blowed as evidence. “I worry that the politically attractive solution to gangs is to ramp up punitive measures. But there’s a case for nurturing the interests of young people so they don’t go down the gang path in the first place.”

Lee, who is Korean-American and grew up east of L.A., has a strong personal connection to these issues. He remembers watching the Rodney King riots on TV when he was 11, and thinking, even then, about racial inequality as “a larger structure that shapes people’s lives and limits their chances.” Later, as a teenager living in Jacksonville, Florida, he had an encounter with that larger form of racism. His best friend, who was African-American, was driving him to a party in an affluent white neighbourhood when police pulled them over. “When the officer saw my friend’s face, he became very aggressive and repeatedly called him ‘boy,’” says Lee. “‘Hey boy, listen to me boy, who are you here to see, boy?’

“I remember thinking that as many times as I’d experienced an interpersonal form of racism – people at school calling me ‘chink’ and ‘gook’ – I’d never experienced it at the systemic level, as my friend did with this police officer. I knew then that at some point in my life I would try to shed light on this and help alleviate some of these inequalities.”

Lee is already working on his next book, Gunshot. “It’s a study about violent trauma and its disastrous consequences on people’s lives,” he says.