How Modern Technology Is Helping to Locate Long-Forgotten Graves

U of T Scarborough students are using ground-penetrating radar and lidar to search for unmarked burial sites Read More

The Society of Friends cemetery in Ajax, Ontario, has dozens of headstones, many of them mossy and sagging with age. But hidden from view – and lost to time – are also a number of unmarked graves that a group of U of T Scarborough students and researchers are trying to locate using modern technology and anthropological sleuthing.

It is one of three old cemeteries east of Toronto that the team of geoscience and anthropology undergraduates are searching using ground-penetrating radar and aerial lidar. They are also scouring local and online archives to help them determine how many bodies are buried.

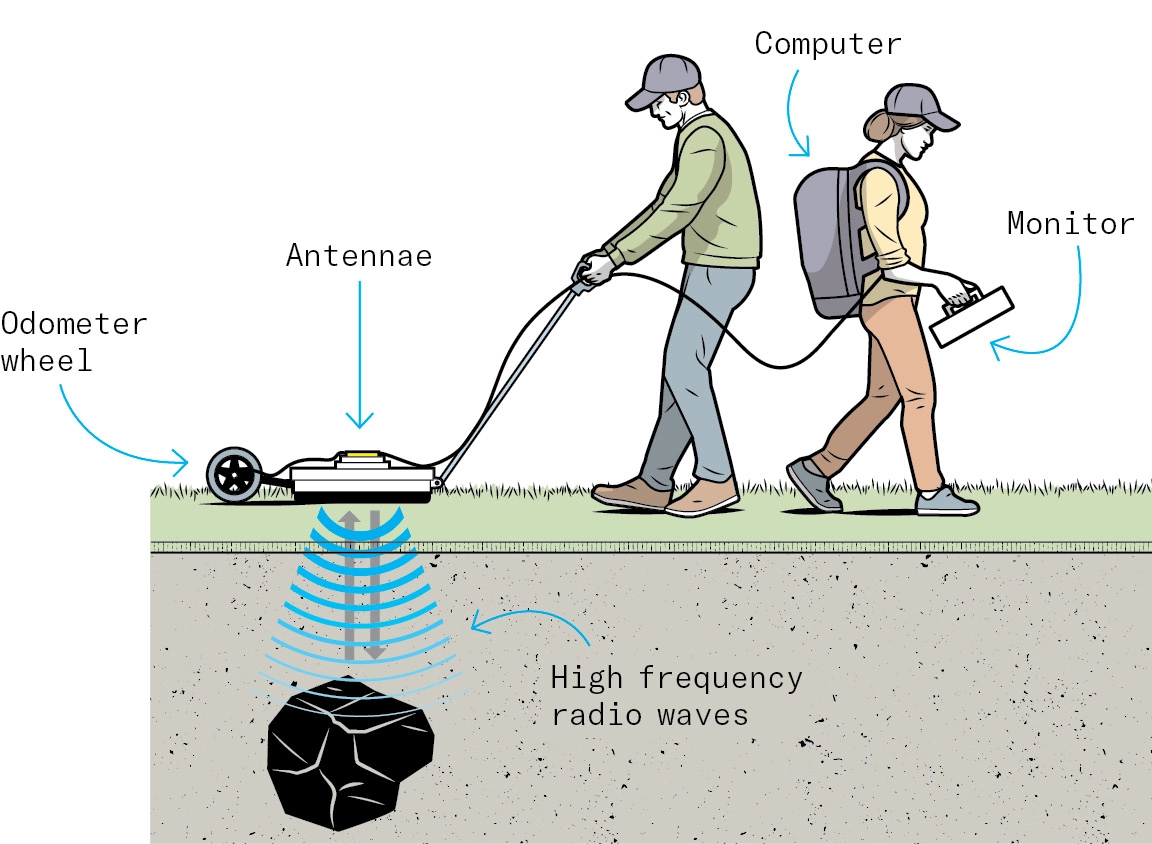

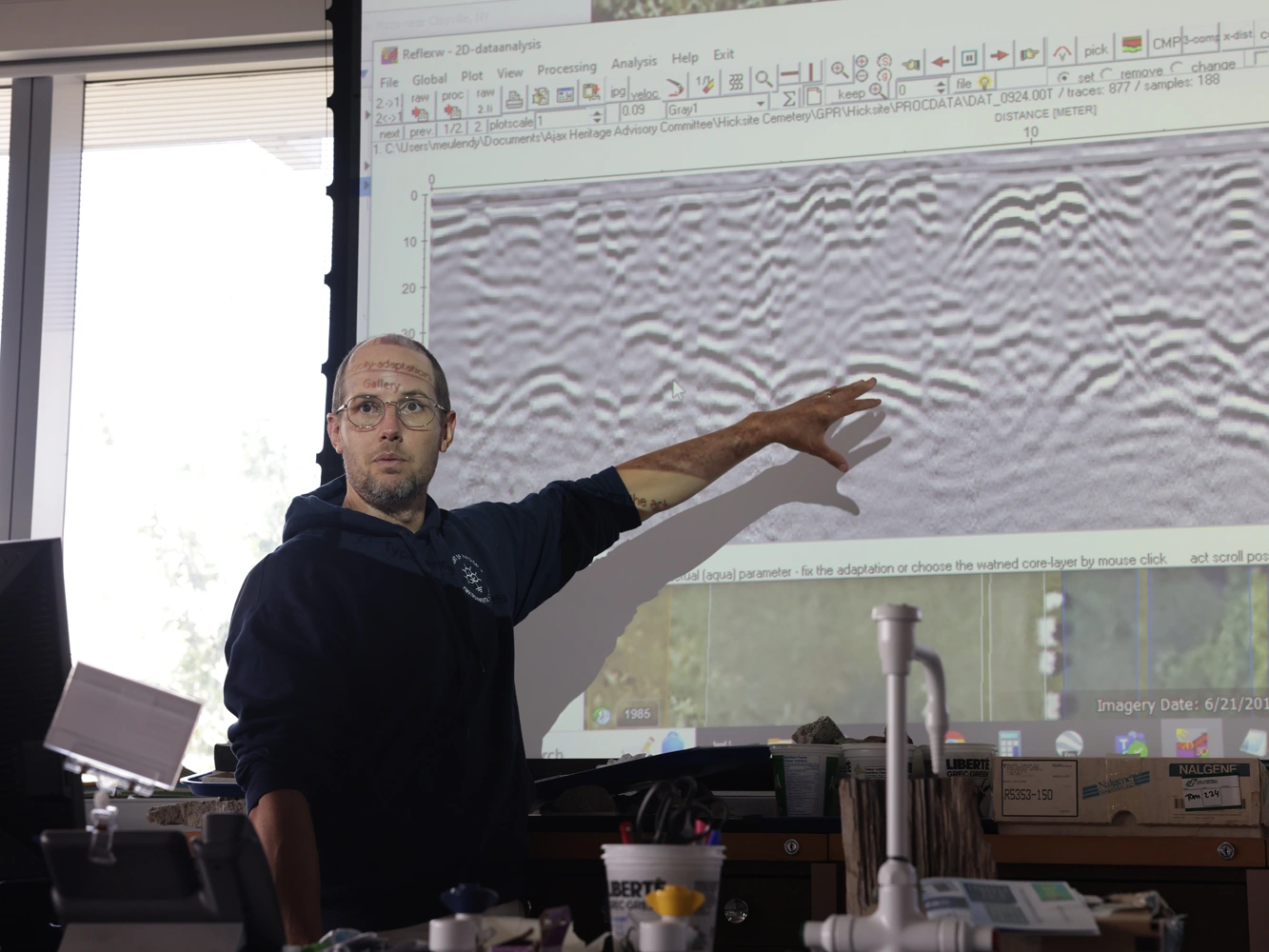

Ground-penetrating radar is the most reliable way to determine, without digging, if something is buried, says Tom Meulendyk, a lab coordinator and geophysics lecturer in the department of physical and environmental sciences. It involves dragging around a device resembling a lawn mower whose antennae send radio waves into the ground.

“It measures the intensity at which the radio waves bounce off an object, like a rock, layer of soil or air pocket,” says Meulendyk. A coffin that is still intact and filled with air will send back a strong signal, but a collapsed coffin will give a different, weaker signal indicating changes in the soil layer.

He first started the project more than three years ago to teach his third-year students how to handle the radar device, which is used mostly for locating buried utilities such as pipes, electrical cables or sewer lines. The team has uncovered dozens of unmarked graves and has been preparing reports for the municipality, which is interested in knowing exactly where people are buried, since two of the graveyards are wedged between current and future housing development sites.

The project also offers an intriguing way to train students on technology used by professional geologists and anthropologists in the field. “We feel like we have an obligation to make sure these graves aren’t forgotten,” says Erin Lam, a fourth-year anthropology and health studies student.

No Responses to “ How Modern Technology Is Helping to Locate Long-Forgotten Graves ”

This is a far cry from earlier methods. I remember, as a graduate student under anthropology professor Norman Emerson, fellow graduates encouraging students to walk around with bent coat hangers, divining for evidence. Lots of post holes were uncovered! Well before the transformation of the word 'like' into a discourse participle I was, like, 'This is nuts!'

Some sample exhumations may be required to verify that the anomalies detected by ground-penetrating radar are indeed human burials. The Negro Burial Ground in Niagara-on-the-Lake, Ontario, which has only one surface marker, is an excellent candidate for this sort of exploration. It deserves documentation.

It's good to see that geophysics is alive and well at U of T, though the geophysics group has disappeared from the physics department. I have been using ground-penetrating radar, including to look for unmarked burial sites, since 1987.

After the radar identifies sites, have any digs been made and studied? If so, what are the findings?

@Felix

Prof. Tom Meulendyck responds:

We haven't made any digs for burials and are unlikely to. Instead, we inform the municipality where the unmarked burials likely are. It’s possible digging might happen if we had found markers and burials on the land surrounding the cemetery, which is slated for development, but that wasn't the case.

That said, we are working on identifying very shallow anomalies in our data which could be associated with grave markers and headstones that have fallen and become buried over time. Once we have a comprehensive map of those, I plan to notify the Town of Ajax’s Heritage Advisory Committee with hopes of excavating them so they can be put back in their proper, above-ground positions.

How fascinating the new technology is! You mention three cemeteries, but only identified two. The Durham Region Branch of the Ontario Genealogical Society is actively updating their cemetery headstone transcriptions from the 1980s. We would be very interested in copies of your findings, especially in view of Prof. Meulendyk's response to Felix on Nov. 26. I am willing to make copies of the branch's 1980s recordings available to the team. We also have a great research team for the family history aspect of things.

Interesting article! Ground-penetrating radar is not a new technology. In the last two decades or so, however, it has been embraced as a research tool by anthropologists and archeologists.

To augment the "divining rod" story mentioned earlier by John Holland, I recall in the early 1970s being at the Draper Huron-Wendat excavation site as a U of T undergrad under the tutelage of Prof Latta. One day, a fellow appeared at the site, claiming to have the ability to "envision" any burial at the site. I thought, "This isn't science!"