The University of Toronto won the first Grey Cup in 1909. That’s a fact. You can find the newspaper clippings about the match in an archive or read about it on the CBC website. But you can also see the actual game ball – looking slightly deflated, the hide scuffed and worn – in a display case at U of T’s Athletic Centre on the St. George campus.

In The University of Toronto: A History, author Martin Friedland describes how a German shell almost killed former professor Harold Innis during the First World War. And if you visit the U of T Archives, you can ask to see the pocket-sized army manual – punctured by a small, round hole – that might have saved the young Innis’s life.

Objects tell stories. And together, U of T’s colleges, libraries and archives boast a wonderful storehouse of artistic and historical treasures. We sent writer Steve Brearton on an expedition – to unearth items that he felt would inspire wonder and surprise, and tell us something we didn’t already know about U of T. This is what he found.

Hart House Who’s Who

American senator John F. Kennedy raised hackles when he addressed a packed Hart House auditorium in the fall of 1957. The future U.S. president had been invited to U of T to speak on America’s role as a world power, but it was his comments about women that kicked up the most fuss. Women had been excluded from attending the lecture because of Hart House’s male-only membership rule, and Kennedy made it clear that, despite the protestations of female students (they picketed outside with signs proclaiming “Unfair!” and “We Want Kennedy!”), it was a rule with which he sympathized. “I personally rather approve of keeping women out of these places,” he said during his speech. “It’s a pleasure to be in a country where women cannot mix in everywhere.”

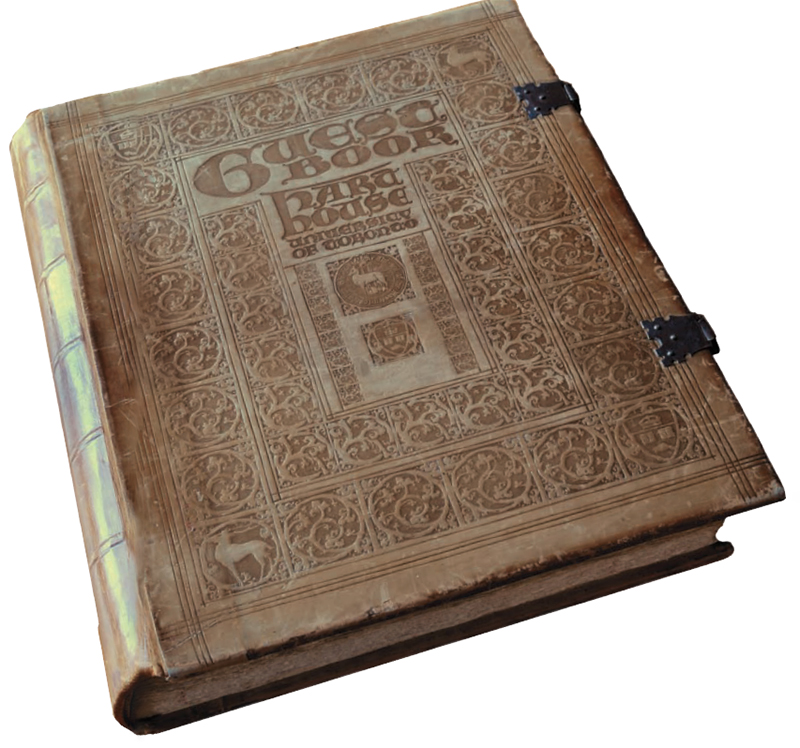

Like almost all visitors to Hart House after 1919, Kennedy signed the guest book – adding his famous name to what is now surely one of the world’s great autograph books. (The original ran out of pages last year and has been replaced.) The leather-bound tome, with a frontispiece by Group of Seven artist Frank Carmichael, reads like a 20th-century who’s who: King George VI, American presidents Dwight D. Eisenhower and Ronald Reagan, writers W.H. Auden, Thomas Mann and Stephen Leacock, economist John Kenneth Galbraith, artist Henry Moore and mountaineer Edmund Hillary among many others. A poetry conference in 1975 yielded two Nobel Prize winners for literature – Seamus Heaney and Octavio Paz – along with noted Canadian poets Irving Layton and Al Purdy. Although a few eminent guests have signed the book on more than one occasion (Queen Elizabeth II signed it in 1981 and in 1951, when she was princess), only one person enjoys the dubious distinction of signing the book twice because he initially inked the wrong page. That was federal Liberal leader Stéphane Dion.

Thain MacDowell’s Victoria Cross

In the pre-dawn gloom of April 9, 1917, Canadian Army captain Thain MacDowell slipped over the top of his trench in northern France and began advancing toward Vimy Ridge. As heavy guns from his battalion rained shells down on German defensive positions, the 26-year-old MacDowell became separated from his fellow soldiers. Attended by only a pair of runners, he continued forward, lobbing a pair of hand grenades at two German machine gun nests that were guarding an underground dugout. MacDowell scored a direct hit. He approached the dugout and called down the tunnel for survivors to surrender. After receiving no response, he proceeded cautiously inside and confronted German troops. Thinking quickly, MacDowell shouted up to an imaginary force to convince his enemy that a substantive number of Canadian soldiers waited above. His ruse worked. Two German officers and 75 soldiers surrendered, and MacDowell sent the enemy troops out of the tunnel in groups of 12 so the runners could take them back behind Canadian lines. A military dispatch by MacDowell indicates just how precarious his situation was that day: “[German] aeroplanes came over and saw a few of my men at the dugout entrance and now we are [under fire]… unless I get a few more men with serviceable rifles, I hate to admit, but we may be driven out.” Although wounded in the hand, he held the position for five days, until relief arrived.

For his bravery, MacDowell (BA 1915 Victoria) was awarded the Victoria Cross, Britain’s highest military honour. He is one of only 94 Canadians ever to have received the award. A replica of MacDowell’s Victoria Cross now sits on proud display among rows of glittering medals in Soldiers’ Tower at U of T. (The original was donated to Victoria University and is held there in safekeeping.) In 2006, Eugene Ursual, a military antiquarian dealer based in Kemptville, Ontario, appraised MacDowell’s Victoria Cross at more than $350,000, but it’s what the medal represents that makes it truly valuable. “It’s the British Empire’s highest honour, and it represents the better side of humanity,” he says.

Two Sides of A.Y. Jackson

In the 1920s, Canadian art collector Esther Williams frequently invited Group of Seven painter A.Y. Jackson to her summer home on Waubec Island in Georgian Bay, Ontario. In gratitude, Jackson created a double sided oil painting on a wood panel specifically for Williams’ cottage. For more than two decades, the picture – almost three metres long and half-a-metre high – sat in a lintel that divided the dining room from a sitting area. Niamh O’Laoghaire, director of the University of Toronto Art Centre, explains that the panel exemplifies Jackson’s desire to make art a part of everyday life: “Placed in a rough-hewn island cottage situated in the very landscape by which it was inspired, the painting became an integral part of the daily experience of those who stayed there.”

Williams eventually sold the cottage – and the painting along with it – to Ernest Howard. The Howard family left the picture where it was, but when the time came to sell the cottage, son Ernest Howard Jr., a Canadian art enthusiast, decided to keep the Jackson panel. He framed the piece himself with wood from a local lumberyard, and hung it in his own home. “My father knew A.Y. had a following,” says Howard Jr., a graduate of Trinity College and a retired investment executive. “But to him, the painting just belonged to the cottage. It didn’t hold any great value.” In 2004, the younger Howard donated the painting to U of T.

The university owns 16 other works by Jackson and dozens of others by Group of Seven artists. But this unusual painting may say the most about the group’s style and purpose. “The Group was against the notion of what National Gallery of Canada curator Charles Hill has called ‘precious objects in gilt frames,’” says O’Laoghaire. “[This] is not only a beautiful painting, but a fabulous and rare exemplar of that Group of Seven ideal.”

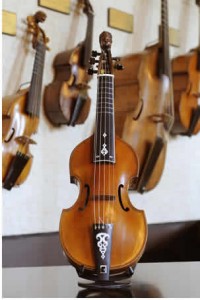

Six-String Wonders

When Professor Joëlle Morton and early music ensemble Scaramella perform at Hart House, the instruments often garner as much attention as the musicians. Scaramella’s co-stars are a collection of six exquisite stringed instruments from the 17th and 18th centuries called viols. “It’s extremely rare to have an opportunity to play a viol,” says Morton, a professor in the Faculty of Music and an authority on the history and development of string instruments. Typically found in museums, the viols came to Hart House in the 1930s through the Massey Foundation and an anonymous donor. They arrived at U of T in a beautiful wooden box thought to be a dowry chest inscribed with the name Margaret Platts and the date 1673. They are now kept in a climate-controlled display case at the Gallery Grill Lounge. Among the superbly crafted instruments are a six-string bass viol by Hamburg’s master instrument maker Joachim Tielke and a French pardessus – the smallest member of the viol family of instruments – by Parisian Louis Guersan. Most closely related to the guitar family, viols were second in popularity only to the lute in Europe during the Renaissance and Baroque eras. In the 17th century, the instruments were a favourite of wealthy, cultured householders who sometimes hosted performances of several viols.

The viols’ quiet, mellow sound suited them to the relatively small rooms of affluent homeowners, but ultimately led to the instrument’s demise. “Viols weren’t loud enough to play in a concert hall,” notes Morton. The violin subsequently shed its status as vulgar upstart, replacing the viol as a lead instrument.

Rumble in Rosedale

In a display case on the main floor of University of Toronto’s Athletic Centre sits a football. It’s worn, could use a little air and looks as if it belongs at the bottom of a utility cupboard. But this is no ordinary piece of pigskin – it’s the game ball from the first Grey Cup. Together with an enormous silver shield proclaiming the Varsity Blues Canada’s football champions and mini-cups presented to triumphant team members, it is also a reminder of the university’s early dominance of one of Canada’s oldest and greatest athletic traditions. In 1909, Canada’s governor general Earl Grey donated a silver cup to be awarded to Canada’s top amateur football team. That December, almost 4,000 spectators turned up at Rosedale Field to watch the Varsity Blues play the Parkdale Canoe Club. With U of T’s school song, “The Blue and White,” ringing through the stands, halfback (and future Argos great) Smirle Lawson led the collegiate squad to a 26-6 victory over their West Toronto rivals, completing a perfect season for the Blues.

Toronto sports commentators considered the first Grey Cup game an anticlimax. The Blues had beaten interprovincial champions the Ottawa Rough Riders the previous week in what most observers had deemed the “real” final. In a report on the Grey Cup game, The Globe noted that a majority of spectators had “confidently expected that Varsity would trample over the Parkdalers to the tune of about 40 to 3.” But when the students led only 6-5 at halftime, the paper said the team had “surpassed themselves in the game against Ottawa and could not be expected to play two such brilliant contests in one season.” The Blues wore “the Paddlers” down in the second half and, in the end crushed their opponents by 20 points. U of T’s championship team claimed the Grey Cup in each of the next two years, but in 1912 lost their bid for a fourth straight title to the Hamilton Alerts. The Blues recorded their final Grey Cup championship in 1920, and amateur teams stopped competing for Earl Grey’s mug in 1954.

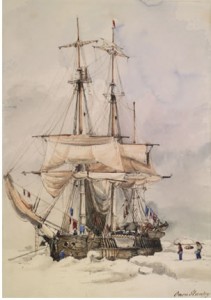

Trapped in Ice

British Navy lieutenant Owen Stanley set sail from England in June 1836 on a journey he would later characterize as “the most unfortunate expedition to the Northern Regions that has ever returned to tell their sad tale of ice and cold.” Stanley’s illustrated diary entries from when he was science officer aboard the HMS Terror convey the fear and wonder he felt as the ship explored the forbidding landscape of northern Hudson Bay. In August 1836, with a bearskin blanket beside his bed and a knapsack with warm clothing at the ready should ice crush the ship, Stanley described feeling the “horror of an arctic winter” before him. “Here end all new hopes,” he wrote on September 23 from Foxe Channel, near the southwest shore of Baffin Island. The Terror remained stuck there in pack ice for 10 months, but during those long Arctic nights Stanley sketched pictures of daily life on the expedition and the subtle wonders of the Arctic environment.

“[Stanley] recognized the inherent beauty of the North,” says Richard Landon, the director of the Thomas Fisher Rare Book Library, which holds copies of Stanley’s manuscript journal and a volume of his drawings. “There’s a real sense of the climate and danger.” Among these early images of the Arctic are drawings of the Terror held fast in the ice and watercolours of “Christmas Amusements” – the ship’s crew in masquerade – as well as landscapes with skilful treatments of the soft Northern light. The Terror limped home in September 1837 with the loss of two crew members, and without having discovered anything, except, perhaps, the possibility of wresting beauty from uncertainty and pain.

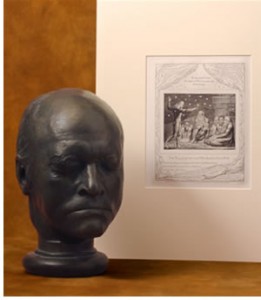

All Things Blake

University of Toronto professor and literary critic Northrop Frye (1912-1991) once suggested that William Blake’s prophetic poetry formed “what is in proportion to its merits the least read body of poetry in the language.”

It may also be true that the E.J. Pratt Library’s collection of wondrous art and ephemera by the English writer and artist is among the least known on the St. George campus. The Bentley Collection (a gift to the university from U of T English professor emeritus G.E. Bentley Jr.) boasts some 2,500 works by and about Blake and his Romantic contemporaries. The collection includes a striking plaster “life mask” of Blake’s head, a unique illuminated printing of Blake’s The Marriage of Heaven and Hell from about 1790 and a pencil drawing of a crowned boy from about 1820.

During his lifetime, Blake enjoyed only minor success, but his boldly expressive and visionary work has influenced more recent artists such as Beat poet Allen Ginsberg and musician Bob Dylan. Bentley notes that when he began collecting Blake’s early editions in the 1950s, few critics considered Blake even one of the major Romantic poets. That changed over the next few decades, thanks in part to Frye’s critical treatise Fearful Symmetry, which was published in 1947 and is widely credited for fostering renewed interest in Blake.

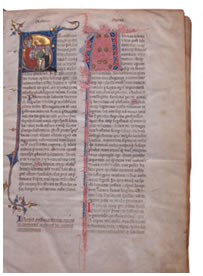

Illuminating Reading

“A medieval library wouldn’t have had everything,” says James Farge, the librarian at the Pontifical Institute for Medieval Studies, located at St. Michael’s College. “But it would have had enough to educate the monks and university students who used it.” Like its predecessors from the Middle Ages, Farge’s collection of theological, philosophical and historical texts, manuscripts and early printed books isn’t exhaustive, but boasts “just enough” of the very best to attract interest from medieval scholars the world over.

In the library’s Joseph Pope Rare Book Room, lined floor-to-ceiling with print and manuscript books, Farge wrestles with a large manuscript, completed in 1329, and carefully opens its aged sheepskin pages. In the upper left corner of the first page is a small picture – an illumination – of Bernard Gui, the bishop, historian and Grand Inquisitor in the Toulouse area in France, presenting the manuscript to Pope John XXII. Gui may be known to contemporary readers through Umberto Eco’s The Name of the Rose, which depicted him as a villain. The manuscript, written by Gui, is a history of the lives of the Roman emperors, Catholic saints and popes. “Manuscripts … [had] a variety of purposes and this is a collection of historical writings by a man who had quite a reputation as an historian,” says Farge. “It also tells the story of how Gui decided to make a present of his works to a pope, hired a scribe to produce a handsome manuscript and was ultimately thanked personally for his gift.”

Battle on Vimy Ridge

Many are familiar with the groundbreaking theories of former U of T professor Harold Adams Innis, but less well known is the story of his near-death experience during the First World War. Innis had enlisted in the Canadian Army as a gunner in the fall of 1916, but was reassigned as a signaller. Signallers, or spotters, watched where artillery shells landed and sent back correcting information so the next shells could reach their mark. On July 7, 1917, at Vimy Ridge, a German shell caught Innis in the right thigh, cutting a round hole through the cover of the compact Field Message Book he kept in his trouser pocket. The resulting injury was serious – it ended his military career – and the book, which now belongs to the Harold Innis collection at U of T archives, may well have saved his life.

A vast collection of documents from Innis’s personal life and career – including his innovative work in economic history, media and communication theory – fill 150 boxes at the archives. Together, they present an intimate and compelling portrait of this great Canadian thinker, as well as insights into the people he influenced. Marshall McLuhan greatly respected Innis’s work on communication, and in one box is a March 1951 letter from McLuhan to his senior U of T colleague that offers a tantalizing glimpse of McLuhan’s emerging theories. “The whole tendency of modern communication…is toward participation in a process,” wrote McLuhan. “There is a real, living unity in our time, as in any other, but it lives submerged under a superficial hubbub of sensation.”

Steve Brearton is a writer in Toronto.

No Responses to “ Battle on Vimy Ridge and Other Stories ”

I’m delighted that Harold Innis had the good fortune to survive the First World War and subsequently enlighten me – and many other former U of T students. Did anyone else make note of the sly humour he shared with his classes? The witticism I remember most clearly is: “The reason for the superiority of the cavalry over the infantry is that the cavalry always has the intelligence of the horses to fall back on.” While on the subject of the military, I should mention that the experience I had in the Canadian Officers’ Training Corps in 1942–43 while attending U of T was excellent. I subsequently trained at a British artillery officers’ school, and what the University of Toronto offered was just as good.

Kenneth L. Morrison

BA 1948 Victoria, MA 1949

Thunder Bay, Ontario

Re: 1909 Grey Cup Winning Team & Smirle Lawson. It was only a few years ago that we discovered that 'Cousin Smirle' was rather a famous football player. We knew of his background as a medical doctor and Chief Coroner for Ontario. We had a very old autographed photo of him that had been given to our grandfather and that led me to Google him. It was quite a surprise to find out so much about him. I have traced a great many of his ancestors and the name Smirle was a family name through his mother's side of the family. Smirle and his wife Pearl (we could never forget those names!) were in frequent contact with our side of the family. There were other members of the Lawson family that were well noted for their athletic prowess, as I discovered on the Internet. The old photo has been donated to the Canadian Football of Hall of Fame in Hamilton, Ontario.