The Secret to a Great Urban Space

One of Canada’s best-known landscape architects, Claude Cormier believes that cities should sometimes make you laugh

When Claude Cormier was asked to redesign Berczy Park, a compact wedge of green space in Toronto’s St. Lawrence Market neighbourhood, there were several competing interests he and his team of landscape architects needed to please: young families, dog owners, office workers looking for a shady place to eat lunch. Five years later, Cormier (BLA 1986) stands and marvels. It’s a cool and cloudy June day, but the park is thronged with mothers and strollers, picnickers and selfie-taking tourists beside a fountain adorned with dozens of cast-iron, water-spouting dogs. Real puppies nose around a patch of gravel designed just for them. Young American elm trees stand sentry, adding harmony to the bustle. “The park has become a magnet,” Cormier says proudly, spreading his arms as if to embrace it all.

If you’ve spent any time in Toronto and Montreal recently, you’ve likely spent some time in Cormier’s embrace. He’s one of the country’s best-known landscape architects. His firm, Claude Cormier et Associés, is as celebrated for the originality and whimsy of its work as it is for its resourcefulness. That work, ranging from pocket parks to innovative installations, is spread across Ontario and Quebec and, more recently, Chicago and Houston: places such as Sugar Beach, with its bubblegum-pink umbrellas, and the surprisingly lush gardens of Evergreen Brick Works. In some cases, these creations are subtle; others are as pleasantly in-your-face as a wedding cake. A graduate of U of T and Guelph and Harvard universities, Cormier opened his Montreal-based firm in 1995 and currently has 50 different projects on the go. In 2015, Phaidon Press included the company in a coffee-table book devoted to the world’s 30 most renowned landscape architects.

In person, Cormier embodies some of the best qualities of his work – he’s friendly, endearing, slightly goofy, brimming with intellectual and physical energy. He’s dressed, as he often is, like a darkening cloud: billowy white shirt, stone-grey trousers, black brogues. He pulls a small suitcase behind him, an accessory he’s rarely without. Though he still lives in Montreal, he’s in Toronto (and elsewhere) several times a month to pitch, plan and work on projects. “I like construction sites,” he says. “I love to see things come together.”

Cormier’s popularity is both surprising and not. With cities such as Toronto growing increasingly crowded and former industrial metropolises such as Pittsburgh having reinvented themselves as beacons for the creative class, urban public space has become both more precious and more complicated. “Living spaces are getting smaller,” says Gregg Lintern (BA 1984 Innis), the City of Toronto’s chief planner, “and even in a winter city, people like to experience the outdoors and being in public space – for health reasons, for social reasons. Many years ago, you’d have everybody over for coffee; now everybody’s going out to the coffee shop or café.” Public parks, specifically, are no longer seen as merely places to picnic or play Frisbee; to developers, government officials and residents alike they are catalysts for community and economic development.

From the High Line in New York City to Toronto’s recently opened Bentway, innovative, adaptive, strategically designed parks – situated in unusual nooks of both congested and disused neighbourhoods – are built to bring people together, jump-start local business and boost tourism. The High Line, initially conceived to resuscitate New York immediately after the uncertainty and turmoil of 9-11, has been a financial and tourism miracle: in 2016, nearly eight million people visited (more than any other destination in the city). And the condos, restaurants and museums that have flourished alongside it will generate about a billion dollars in tax revenue over the next 20 years. Less quantifiably, such public spaces also make city-dwellers happier and urban landscapes more enchanting. As Jake Tobin Garrett (MSc in Planning, 2012), a manager at the Toronto-based charity Park People, says of Berczy Park, “Cities are for living in, but they’re also for having fun and shedding the stress of our daily lives. I dare you to walk by this park without being drawn in with a smile on your face.”

Cormier’s public spaces can be fanciful, expensive to build and even, to some eyes, weird. When he was a kid, growing up on a dairy farm in Princeville, Quebec, he dreamt of studying plant genetics so he could invent a new flower, and his best-known projects do involve a kind of hybridization, blending disparate elements – botanical, historical, artistic – to form something singular. “The way I use history and art – I’m assembling things in a way to create a different kind of space,” he says. When he conceived of Berczy’s Victorian-inspired fountain with its eccentric canine adornments, he was told by skeptical city officials that dogs had nothing to do with art. In response, he and his staff combed through archives and, of course, discovered the opposite. “We did our research and found dogs everywhere in art history,” Cormier says, smiling. “It goes back 5,000 years!”

Cormier’s encountered such opposition frequently throughout his career – his controversial “Lipstick Forest,” at Montreal’s Palais des Congrès, a futuristic winter garden of 52 concrete “trees” painted bright pink, was derided by local newspapers; the cost of the umbrellas for Sugar Beach outraged some Toronto city councillors. The approval process, with all its potential setbacks and multiple stakeholders, he says, is a constant reminder that his work could be rejected. But cost versus value is something that Cormier thinks about for each project, and he is adamant that, if anything, we don’t spend enough money on our parks, streets and plazas: “What is spending too much? Is it spending $100 a square foot on the public realm that’s used by everybody, or $600 or $800 a square foot on the condo next to it? Sugar Beach, which was initially considered too expensive, is a great example of how urban infrastructure can increase the value of the area around it,” says Cormier. “When you do it cheaply, it’s wasted, because people won’t come back.”

A good landscape architect must be part ecologist, project manager, visual artist, pitchman and politician. Every landscape architect who works with urban public space has to look at the built environment and assess how best to augment or enhance those forms with a combination of plant life, street furniture and public art. And every landscape architect who works with urban public space has to collaborate with developers, city officials, community residents and engineers. But a great landscape architect is also a bit of a pugilist. “You have to be ready for a fight,” says Cormier, “because there will always be something on a project that you will need to stand up for. We have a certain level of idea we fight for, and we don’t give up.”

He’s insistent that these ideas don’t just blend into the background. He’s been likened to landscape architects such as Frederick Law Olmsted, who designed New York’s Central Park, and Martha Schwartz, who dropped a giant boulder into Toronto’s Yorkville district. Like these projects, Cormier’s work is defiantly visible, asserting its own presence and value. “I like things with personality,” he says. “The whimsical aspects open up a different sense of perception and people respond well to it.” Thanks to the success of Berczy, Cormier is now working on an amusing response to it west of downtown – this time, featuring about 20 cast-iron cats – as a small part of the massive redevelopment at Front Street West and Spadina Avenue known as The Well.

One could describe Cormier as a kind of Robin Hood of landscape architecture. The analogy’s not perfect – he doesn’t exactly rob the rich to give to the poor – but what he is doing is using the funds available to him to create something beautiful that everybody can enjoy. It’s no secret that our major cities, from Toronto to Tokyo, are becoming increasingly unaffordable – that income and spatial inequality have become almost intractable problems. But public spaces such as Cormier’s serve as compelling, vital arenas where citizens – no matter their income level or background – can interact. The more appealing those places are, the more likely those interactions. “If you design something to induce positive behaviours,” Gregg Lintern, the city planner, says, “you’re going to have a richer, healthier, more socially cohesive city environment.”

Cormier insists his first priority is the city-dwellers that live with his projects every day. “We’re doing it for the people,” he says. “We are working with developers who are starting to understand that if you do a good landscape, it’s going to bring them value. A way to do that is through good open-space plans, good amenities, good integration with the street. Then the public feels that they have something there for them.”

Cormier grabs his suitcase. He has to get to more meetings, including one for a project whose details he couldn’t yet disclose except to say, “We are having fun imagining it. We are laughing. Laughing!” He looked like someone about to open a Christmas present. “But I think you can do that in many projects. You just need the guts to do it.”

Millennium Park, Chicago

For Cormier, the magic surrounding Chicago’s centrepiece park begins with “Cloud Gate,” the highly reflective steel sculpture by artist Anish Kapoor commonly known as “The Bean.” Photo-takers have made it their first stop ever since the park opened in 2004. “People see themselves in it, they interact with it and it’s beautiful to watch,” he says.

The High Line, New York City

The park sits in an old, elevated train track on the city’s west side that was almost torn down before concerned citizens stepped in to save it in 1999. The park opened a decade later, and the 2.4-km ribbon of green is now one of New York’s top attractions. “It shows what can happen when you have a bold vision and a beautifully crafted landscape that allows the community to come back,” says Cormier. “I wish I had it in my portfolio.”

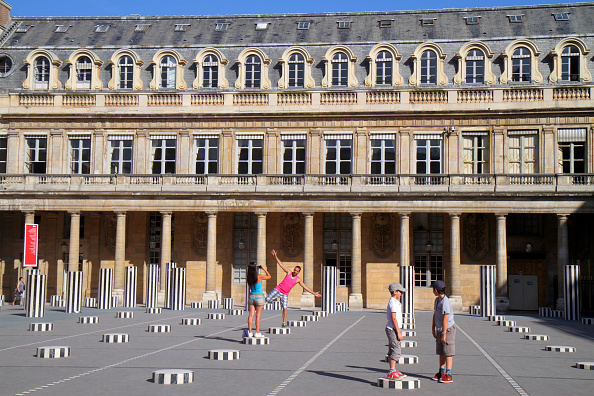

Les Deux Plateaux, Palais-Royale, Paris

Artist Daniel Buren’s striped “licorice” sculptures were hugely controversial when they were built in the palace courtyard in 1986. Yet the black and white marble columns of varying heights “became pedestals that people would stand or sit on to have their pictures taken,” says Cormier, who loves the conflict between the 17th-century baroque palace and Buren’s contemporary art. “It’s like juxtaposing different languages. But by creating this clash, you make each one look more magnificent.”