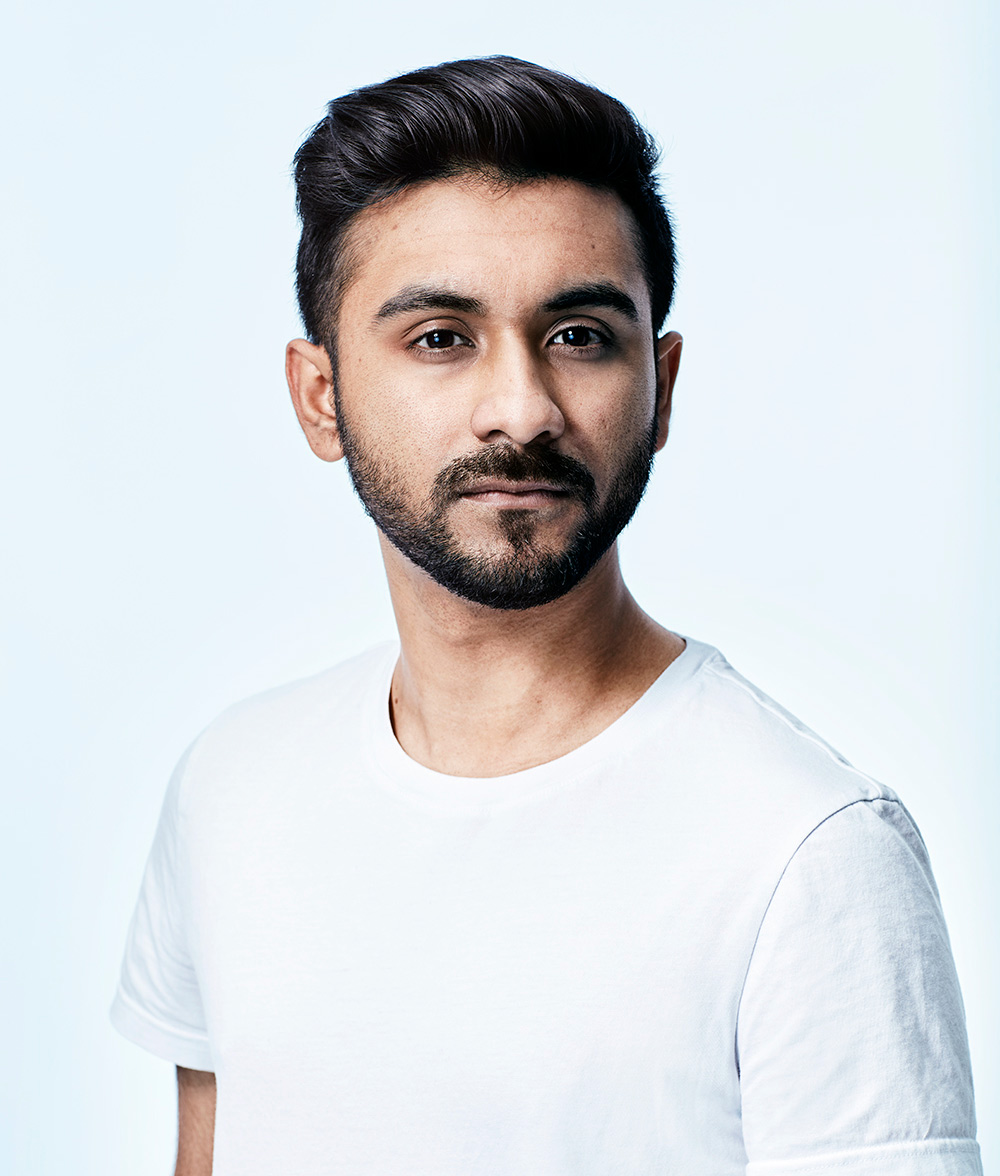

In July 2016, Tahmid Khan was visiting Bangladesh when a horrifying series of events led to his arrest and imprisonment for a crime he did not commit. Here, he writes about his ordeal.

A photo nearly destroyed my life. Google my name and it’s one of the first images you’ll see. It shows me standing on the roof of the Holey Artisan Bakery in Dhaka the morning of one of the worst terrorist attacks ever to occur in Bangladesh. I’m the guy in the black tee, holding a gun. I’m talking to two men, including a terrorist. There appears to be a smile on my face.

It’s not a good look. But there’s so much more to that photo than meets the eye.

Unfortunately, though, people tend to arrive at conclusions based on limited knowledge. Worse, they cling to their beliefs despite plenty of evidence to the contrary. What happened to looking beyond first impressions and digging deeper to discover the truth?

A lack of concern for the truth has serious consequences. For me, they were personal – and harrowing.

I was in my third year at U of T, studying global health, when I landed a four-month internship with UNICEF in Nepal. I was very excited.

The internship was to begin shortly after the Islamic festival Eid. At my parents’ suggestion, I decided to spend Eid with the family in Dhaka before heading to Nepal. On the evening of the day I landed, I went out to meet two of my friends. We gathered at Holey Artisan Bakery and ordered ice cream; we didn’t plan to stay long.

Suddenly, we heard what sounded like fireworks. I turned and saw a group of men storm the dining area. They were firing machine-guns. It was louder than you can imagine. The sound haunts me to this day.

The terrorists killed several people – foreigners and others they identified as non-Muslim – and held the rest of us hostage overnight. Early the next morning, they ordered me and another hostage, a Briton of Bangladeshi heritage, up onto the roof. They sent out the other hostage first. Then they forced me to hold an unloaded gun and sent me out after him.

I believe the terrorists were using me to see if security forces would open fire at the sight of a potential attacker. That’s why they gave the gun to me – the bearded, brown guy in his 20s. After several minutes, one of the terrorists stepped onto the roof. We stood there, exchanging words, when a tourist in a nearby building snapped that photo.

The three of us returned to the dining area. A whole night of pleading and negotiating with the attackers seemed to work when a few hours later they let some of us go. Security forces then stormed the restaurant, killed the terrorists and rescued the other surviving hostages.

By this point, the police had seen the photos. For me, this was a case of “out of the frying pan, into the fire.” I survived the hostage situation only to find myself taken into police custody as a suspect in the attack. In the days that followed, the photos were all over the news. On social media, people called me a terrorist. Some TV commentators lied, saying they had damning information about me.

Why did people say these unfounded things? It’s impossible to know for certain, but I have a theory. I’m fortunate to come from a well-off family. The majority of the terrorists were from affluent backgrounds, too. For many observers, this superficial similarity provided enough of a reason to label me a terrorist as well. They portrayed me as a rich kid who had lost his way and fallen in with extremists.

Others questioned my body language that morning on the roof. Why would I be talking to the terrorist rather than cowering in fear? Why wasn’t I too petrified to move? The answer is I did what I needed to do to survive. This meant trying to talk my way out of trouble. I tried to convince the terrorist that his crew didn’t need to hold us hostage. I told him they wouldn’t win a shootout with security forces and that their best course of action was to let us go.

As he and I talked, he randomly asked me if I played video games – specifically, first-person shooter games. It was such a bizarre question in that moment that I cracked the faintest of half-smiles. Not because I was relaxed, but because I felt bemused, confused, nervous and tired.

I found out later that for most of the time I was up on the roof, a police sniper’s laser sight had been trained on the back of my head.

I was supposed to spend part of my summer enjoying a life-changing experience in Nepal. Instead, I spent those months languishing in police custody, remand and prison.

Outside, a battle of narratives was underway. I have to thank my friends and family for using social media to debunk the falsehoods about me, particularly via the #Free-Tahmid campaign. I found out about that during an interrogation session, when I glanced over at the investigator’s phone as he combed Facebook for posts about me. It gave me strength and courage during that dark and lonely period.

I had a lot of time to reflect on my life to that point. I had struggled as a U of T student. Even though I was passionate about public health and climate change, and was determined to use my education to make a difference, the academic demands were overwhelming. I felt faceless in the sea of students, and, as a commuter student, I felt isolated from campus life.

I didn’t think the university would notice my absence. But I was wrong.

U of T president Meric Gertler wrote a letter to then-Minister of Foreign Affairs Stéphane Dion assuring that I was a student “in good standing,” and stating that U of T was prepared to assist in efforts to secure my access to a lawyer and consular services, and to advocate for my rights.

The letter was read out in court. I had to suppress a smile because I never thought I’d see the day when I’d be described as a student “in good standing.” Only later did I learn that “good standing” means you haven’t been suspended, you’re not on probation and you have a cumulative grade point average of at least 1.5!

But I was deeply moved that U of T was willing to speak up for my rights when my innocence had not yet been proven. I had been involved in a major international terrorist attack, and U of T came to my defence. I realized that the university wasn’t only about academic achievement and competition. It was willing to take a stand for what was just.

I believe President Gertler’s letter contributed to my acquittal. When U of T speaks up for you, it means something.

After my release, all I wanted was to enjoy a quiet, normal life. I was fortunate that, for my first semester back, St. Michael’s College gave me the chance to live on campus. The Centre for International Experience offered me a job. I received a lot of support from Student Life, the Office of the Vice-Provost for Students, the Registrar’s Office and my department: human biology. I was feeling better about my life at U of T. But for a long time, I didn’t speak publicly about everything that had happened to me.

Then, in February 2019 – more than two years after I regained my freedom – I decided to tell my story in a TEDx Talk at U of T Scarborough. Many news outlets in Bangladesh as well as North America covered my presentation. However, the ones that had spread despicable lies about me in the wake of the attack conveniently neglected to give it any attention.

I guess some people have a hard time accepting they are wrong. Others continue to spread lies to this day, especially behind the veil of online anonymity. On YouTube, for example, in the comments on my TEDx Talk, they still call me a terrorist – despite my acquittal and all the evidence to the contrary.

Thankfully, social media can also help propagate the truth and counter false narratives. This doesn’t repair all the damage, though. Those who spread dangerous falsehoods are rarely punished, while people on the right side of the truth suffer. (I can’t speak comfortably about everyone involved in my ordeal because my family still lives in Dhaka. They’ve been through enough.)

What I’ve taken away from this traumatic experience is that the truth is always worth fighting for – even if there’s no guarantee of a fair outcome. The pursuit of truth is as important as the outcome, because it gives you direction. In seeking truth, you’re forced to dig deeper, consider different possibilities and understand the fuller context.

I feel like everyone should know this, but I am not sure everyone does. It’s worth repeating. The truth is important. It can be a matter of life or death. My story proves that.

In June 2019, Tahmid Khan earned a BSc in human biology, with a specialization in global health, from U of T. He will launch a speaker series about public health, combining his academic interests with an appreciation for civic dialogue, and plans to attend graduate school at Columbia University in New York.

As told to Rahul Kalvapalle

No Responses to “ The Truth Saved My Life ”

I can certainly attest to the truth being important. Tahmid is extremely brave and I am glad U of T helped him.

I went through an experience of false news, generated by a vindictive former employee who smeared my reputation in the media while I was working as a professor in the European Union. Even after my complete exoneration, the attacks from this ex-employee continued. Thankfully, my husband and I decided to return to Canada. My Canadian university, Universite de Montreal, determined the truth and gave me the support I needed to keep going.

Individuals who start lies -- in Tahmid's case and mine -- have no conscience. You cannot expect them to care. My ordeal, although long (spread over four years), was in no way comparable to the horrific experience he went through. I share my experience as a fellow U of T alum, as further evidence of how fake news is extremely destructive, and how the truth can prevail. I am sure there are many others affected by fake news and I hope they too will find the support they need for the truth to shine through. Thank you for sharing your story. I wish you all the best in your future endeavours.

So much truth spoken in such a very small space. I am happy for Tahmid Khan in that the harrowing saga has ended reasonably well for him. It could be better, but such is life. We are grateful for what we receive and accept that some things will forever be out of our reach such as Tahmid's wishing a better outcome for his relatives, and quite possibly, a wish to have his reputation restored.

I am so glad you finally told your story publicly. I am originally from Bangladesh and have a close connection with U of T. Good to know it played such a pivotal role in your fight for truth. Pursuit of truth without bias should rightly guide us, I believe that very strongly. Hopefully your story will motivate some to that end.

I cannot imagine the despair you were feeling. I am so happy for your release and subsequent victories. Thank you to U of T.