Chronic diseases such as Type 2 diabetes take a massive toll on Canadians, both on our health and on our health-care system. Since obesity and inactivity are major risk factors for diabetes, the most common intervention so far has been for doctors to counsel their high-risk patients to lose weight and exercise more. That’s good, but is that the most effective approach as diabetes rates continue to soar? Drawing on machine learning for her research, Laura Rosella, an epidemiologist and professor at U of T’s Dalla Lana School of Public Health, suggests that broader community-based actions could prevent more cases and save more money than targeting individual patients.

When Rosella took the risk-prediction algorithm that she and her team developed – the Diabetes Population Risk Tool – and applied it to Statistics Canada’s health information on the population, a clear picture jumped out at her. Beyond obesity, influential risk factors to predict who would get diabetes include lack of access to physical activities, social isolation, food insecurity, low socioeconomic status and chronic stress. The data suggested that making investments to address these factors could prevent disease.

Public health departments had suspected as much, but this was the first time they had the evidence to support it. Rosella’s algorithm would now enable them to clarify which populations to target for prevention efforts, and to calculate the health and economic benefits in their own municipalities from various investments, such as improving neighbourhood walkability. This opens up a whole new way of looking at health care, says Rosella, who holds a Canada Research Chair in Population Health Analytics. “It’s not a tweak. It’s going to actually change the way we think about disease and care.”

Rosella’s research caught the attention of the Region of Peel, west of Toronto. With its large South Asian community, a group that has a genetically higher risk of diabetes, and its car-dependent suburban neighbourhoods that may discourage walking, the prevalence of diabetes in Peel is 26 per cent higher than the provincial average. Rosella’s algorithm showed that at the current rates of the disease, the projected health costs over 10 years would be $689 million. “That was really compelling,” says Julie Stratton, an epidemiologist with Peel Public Health. “This tool allows us to provide the information showing why it’s really important to make investments now.”

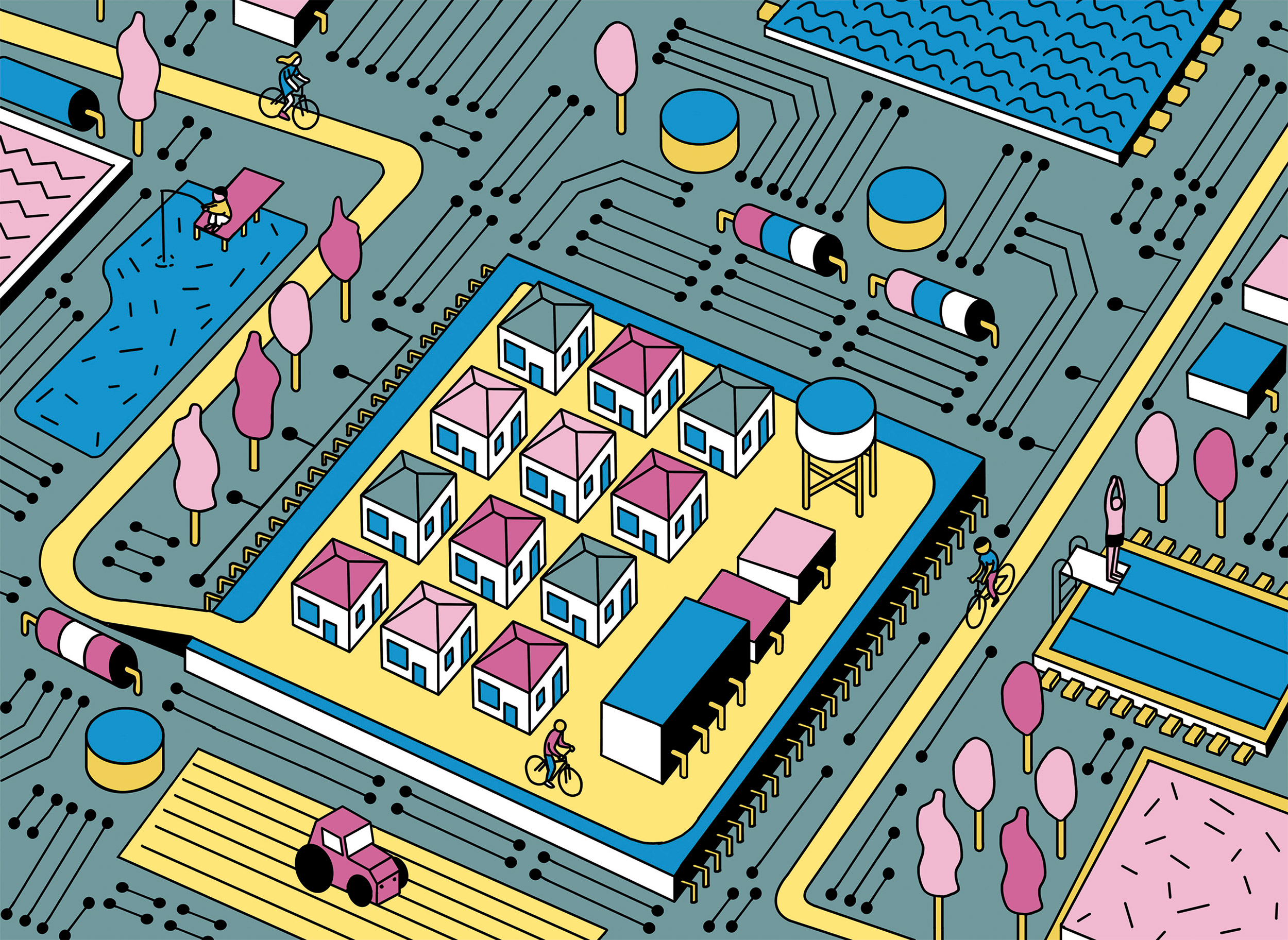

These investments might include anything that encourages people to be more physically active, such as safe walking routes, bike paths and more public transit for commuting to work (which increases the amount that people walk). With the vision of building healthy communities, Peel’s official plan now requires that new development applications undergo a health assessment, which supports pedestrian- and transit-friendly neighbourhoods.

Other municipalities are becoming interested in Rosella’s research, too, especially since it enables them to attach dollar figures to various health risks. In the Greater Toronto and Hamilton Area, the analytics found that diabetes-related medical costs attributable to inactivity alone exceed half a billion dollars every year. Ottawa Public Health used the algorithm to calculate that a long-term plan to improve public transit and build more bike paths would prevent some 4,000 cases of Type 2 diabetes over 10 years.

Building on her initial success, Rosella has since spearheaded the development of other predictive algorithms, such as the High-Resource User Port. A mere five per cent of Ontario’s population consumes about half of the province’s health-care budget, so Rosella set out to predict which groups would likely become future high users of the health-care system. She and her team followed health-care use of 60,000 people over five years.

Healthy people who were most dissatisfied with life had triple the rate of developing a chronic disease compared to those who were most satisfied with life

To their surprise, they found that in addition to the expected predictors of age, chronic conditions and smoking, an equally strong predictor of becoming a high user was people’s own feelings about their well-being. “This reinforces the need to listen to patients and ask them how they feel about their health,” Rosella says.

Rosella followed up the initial study with one using a more global measure of people’s self-rated life satisfaction and tracked them for several years. She found that healthy people who were most dissatisfied with life had triple the rate of developing a chronic disease such as diabetes, heart disease or chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, compared to those who were most satisfied with life. “I’ve been studying risk factors for chronic diseases for 15 years, and this was one of the biggest effects I’ve ever seen,” she says. The relationship between life dissatisfaction and becoming a high-cost health-care user persisted even after adjusting for income, activity levels, mood disorders such as depression, and lifestyle behaviours.

There’s no pill for life dissatisfaction, unhappiness or loneliness, Rosella says. But instead of thinking about a patient only in terms of high blood pressure, anemia or borderline diabetes, she suggests that equally important considerations include whether one lives alone, has sufficient income or has a safe place to walk. “We need to think of patients as people, and all the complexities that surround them.” She adds that there may be a growing role for social prescriptions, such as a doctor’s note allowing free admission to a museum or art gallery. She points out that last year the U.K. government appointed a minister of loneliness.

Rosella, who in 2018 was named one of Canada’s Top 40 Under 40, is a faculty affiliate at Toronto’s Vector Institute for Artificial Intelligence. In 2018 she received a Connaught Global Challenge Award to launch a global network that will use predictive analytics to address world population health challenges. Says Rosella: “AI has huge potential to be beneficial both for population health and the sustainability of the health-care system.”

Paul and Alessandra Dalla Lana donated $20 million last year to U of T’s Dalla Lana School of Public Health to support research such as Prof. Laura Rosella’s. This recent gift comes almost a decade after their first $20-million gift to establish the school.