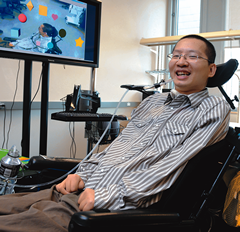

Although he’s paralyzed from the neck down and can’t hold a musical instrument, Eric Wan recently performed Pachelbel’s Canon with musicians from the Montreal Chamber Orchestra. The stirring rendition, filmed at the Royal Conservatory of Music in Toronto without an audience present, was accomplished through a remarkable piece of software engineering that Wan helped design. “I was astonished that I was able to perform with professional musicians,” says Wan, 33, a computer engineer at the U of T-affiliated Holland Bloorview Kids Rehabilitation Hospital.

Called the Virtual Musical Instrument, the computer program enables almost anyone to make music – including people with any level of physical disability. The virtual instrument works with any standard computer and webcam. On the screen, budding musicians see their own image, on which are superimposed coloured shapes representing different notes, chords or entire bars of music. The camera captures movement over these shapes – whether it’s the waving of an arm, nodding of the head or even blinking of an eye – and translates it into musical sounds, which can be programmed to sound like any of 128 instruments.

The invention combines Wan’s two loves: computer programming and music. In 1996 he was a healthy, violin-playing, 18-year-old computer whiz when he suddenly developed transverse myelitis, an inflammation of the spinal cord’s nerve sheath. Wan spent four months on life support before gradually learning to breathe consciously. He now uses a ventilator only at night.

Three years after becoming quadriplegic, Wan started taking computer-engineering courses part time at the University of Toronto. “I just did it out of interest, not to pursue a degree,” he says. For many years, he has relied on a computer system with a head-tracking device. A camera on top of his screen tracks the movement of a sensor on his eyeglasses. Moving his head moves the cursor, and lingering for more than a quarter of a second clicks it. “I’m able to control the mouse cursor as efficiently as a healthy person,” says Wan. He graduated with a bachelor of applied science in 2010, 11 years after he began.

For his undergraduate thesis, Wan used a vocal sensing switch to allow people with severe physical disabilities to control a power wheelchair with their voice. For his master’s degree, Wan is designing a new technology for people who are unable to move or speak that translates thoughts into functional activities, such as turning a light on or off or indicating yes or no.

But it’s the virtual musical instrument that continues to make headlines. Last October, the four-member design team – senior scientist Tom Chau, music therapist Andrea Lamont and engineers Wan and Pierre Duez – travelled to Dearborn, Michigan, to receive the da Vinci award, the equivalent of an Oscar for adaptive and assistive technology. It was the first time Wan had been on a plane since coming to Canada from Hong Kong as a 10-year-old.

With his programming skills, sharp memory and quiet charm, Wan is a valued member of the team. “First and foremost he’s a good engineer and a good researcher, and he’s great to get along with,” says Duez. “But he also brings the personal experience of someone with physical limitations, and he acts as a reminder of that.”